Training of Electrical Engineers – how it was done in 1894

A very interesting process called electrification occurred in Britain and other countries from mid-1880 until around 1950. This process included the changeover from line shafts powered by water wheel, turbine, windmill, animal power or steam engine to electric motors. Electrification was called “the greatest engineering achievement of the 20th century”. Like with all great discoveries it didn’t happen overnight. It was preceded by the invention of the carbon arc lamp by Sir Humphry Davy in 1802, then in the 1830s with Michael Faraday discovering the law of electromagnetism and electromagnetic induction and discovering the operating principle of the electric generator. The light bulb, with its numerous inventors, followed. Although there were many inventors, the most successful of them all were Joseph Swan (1878) in England and Thomas Edison (1879) in the USA. Swan’s house, in Low Fell, Gateshead, was the world’s first to have working light bulbs installed. The Lit&Phil Library in Newcastle, was the first public room lit by electric light, and the Savoy Theatre was the first public building in the world lit entirely by electricity.

The world has changed and with this change new demands appeared.

This is when the time came to open The Electrical Standardizing, Testing and Training Institution, Faraday House, Charing Cross Road, London. This is where our new collection of school magazines (now being catalogued in the Rare Books Department) comes in; because in its depths we hold one prospectus from this Institution – The Training of Electrical Engineers (Harrison & Sons, London 1894).

“When in 1881 to 1882 the first great movement in Electric Lighting occurred, the demand for qualified practical men was found greatly to exceed the supply. There were numerous Engineers and Electricians but very few Electrical Engineers, and to this was due not a few of the failures and heavy losses that then took place. To meet the difficulty the Electrical Engineering College was founded in 1882, and, while the fees were arranged with a view to the college being self-supporting, it fulfilled its main object of supplying competent trained engineers to the industry” – we read on page 5.

In 1887, Electrical Engineering College grew and changed its name to The Electrical Standardizing, Testing and Training Institution. It was then founded “by a number of gentlemen – largely interested commercially in Electrical Engineering – who have felt the existing need of thoroughly trained men for the vacancies which have to be filled in the numerous and increasing branches of the work” (p. 7).

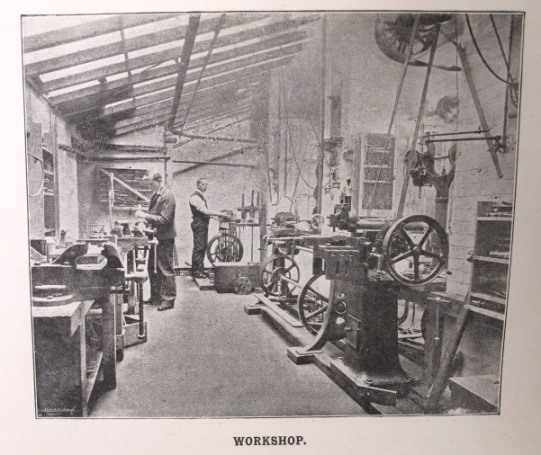

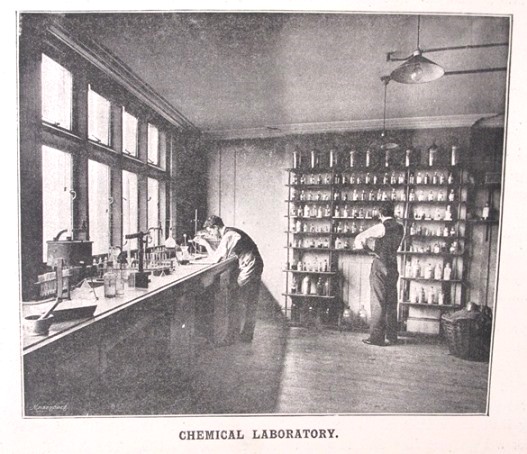

The College associated itself with several leading Electricity Supplying Companies (which list is given on pages 1-3), with manufacturing and contracting concerns and with individual members of the electrical profession. By working closely with them it provided not only practical aspects of the training but also an opportunity for the future employment for its students. The course consisted of three years training, with the middle year devoted to practical training at one of the companies involved with them. In quite a strong way the College disassociated itself from the idea of the Apprentice. “A lad goes into the workshops (we read on page 9) understanding nothing of what is going on around him, and is seldom anyone’s business to teach him. He is set to file brass plates or to make screws, and soon grows disheartened with the monotonous work. If exceptionally quick and observant, he may pick up a good deal; but he is self-taught, and probably retains for life the limitations of the self-taught man. Too often he will leave the works knowing little more than when he entered them, (…) the few workmen are too busy to teach, even if they knew how; the student can hardly learn anything from his neighbours – students as untaught as himself; he grows idle or indifferent; or perhaps, throws up the whole thing in disgust”. Straight after that statement follows the description of a student from Faraday House and his position in the world of working engineers. Letters of gratitude and praise from former students follow afterwards from pages 13 to 22.

The prospectus is filled with the photographs of students at work in different rooms of the Institution. We can see students working in the workshop, dynamo room, physical laboratory, chemical laboratory and private experimenting room (room 19).

There is a vastness of 122 years from the moment this prospectus was published till now. It is incredible how far we have come and what we have achieved as a human race. But it is also slightly scary and at the same time amazing to think where are we going to venture in the next 122 years. Let us just imagine someday in the future, in year 2138 for example, looking at old pictures of engineering labs from the year 2016. What do you think our future selves would say?

I live in Faraday House! It’s great to see old photographs and know something of its history

This is definitely a bit different from my City and Guilds Electrician course 😀 I completely agree – the amazing developments over 122 years in and the more amazing developments in the next 12 years. Imagine actually jumping such a lage period in time rather than experiencing each year, one after the other. It’s no wonder we find films like Back To The Future so entertaining.