A Schoolbook for Chinese Emperors

The fourth of our ‘Treasures of the University Library’ talks was given by Charles Aylmer, Head of Chinese Collections:

In 1594, an ambitious scholar by the name of Jiao Hong was appointed tutor to the ill-fated Heir Apparent Zhu Changluo 朱常洛 (1582-1620), who would later reign as the Taichang 泰昌 Emperor for only 30 days (28 August to 26 September 1620). For the education of his important new pupil, Jiao Hong compiled a schoolbook, Yang zheng tu jie 养正图解, meaning ‘Illustrated explications of the cultivation of rectitude’. The title is derived from a quotation from the Yi jing 易经 (Book of Changes) ‘Meng yi yang zheng 蒙以养正’, ‘to strengthen what is right in a youth’ (Hexagram 4). Its purpose was to inculcate the basic tenets of Confucianism, exemplified by sixty moralistic anecdotes drawn from the lives of earlier Heirs Apparent in Chinese history. Each episode comprises a brief narrative and a paraphrase in simpler language more suitable for the comprehension of a child. Illustrations by the artist Ding Yunpeng 丁云鹏 (b. 1547) accompanied each story, to make reading the book more enjoyable.

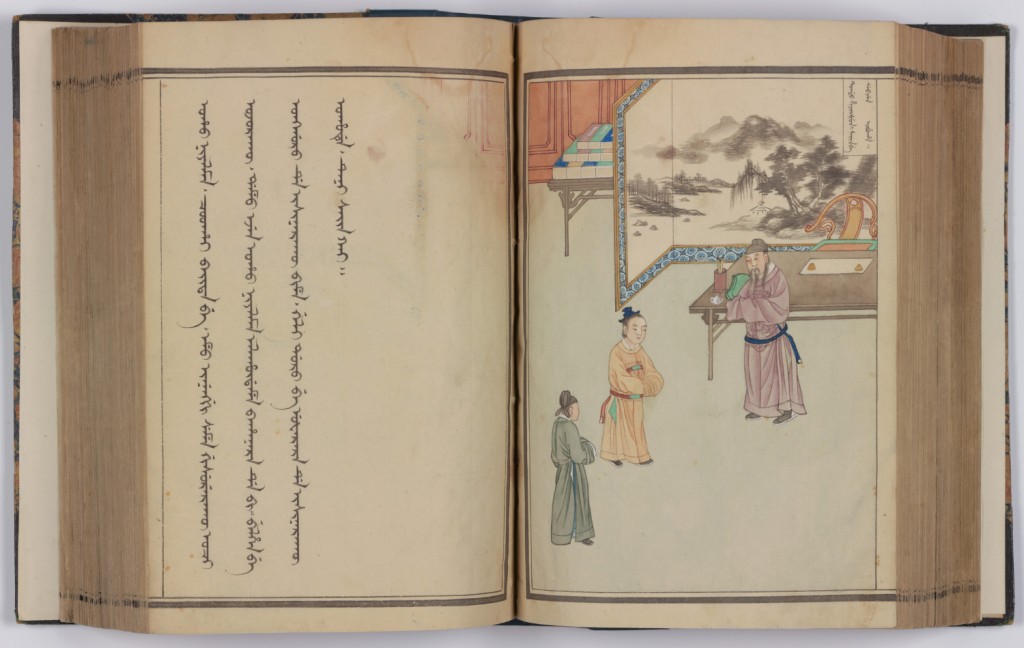

Double-page opening of ‘Tob be hūwašabure nirugan suhe gisun-i bithe’, with a watercolour miniature; undated [?18th century], FC.99.206

The book’s circulation was not confined to the late sixteenth-century imperial court, however: it was printed first in 1594 and was followed by two subsequent editions. It was also translated: a Manchu version – entitled Tob be hūwašabure nirugan suhe gisun-i bithe – was made by and for the use of the successor dynasty. However, it was never printed, and is exceptionally rare: Cambridge University Library possesses one of only two surviving handwritten copies (the other is at the National Library of China). The Cambridge copy is undated, but may have been made in the eighteenth century.

The story illustrated above typifies the continuity of historical experience so highly prized in Confucian teaching. It refers back to an event a thousand years before Jiao Hong’s time, but set in an identical context: the imperial tutor Wang Gui 王珪 (571-639) instructing his pupil, Li Tai, Prince of Wei 魏王李泰 (618-652), fourth son of Emperor Taizong, and invoking an even earlier precedent from the Eastern Han dynasty in order to give him moral guidance:

‘Li Tai respected his tutor Wang Gui. Whenever he met Wang Gui, he was punctilious about observing the correct ritual due to a teacher. Wang Gui for his part also comported himself as a teacher should. One day, the Prince asked Wang Gui, “What is fealty (zhong 忠) and what is filial piety xiao 孝?” Wang Gui replied, “His Majesty the Emperor is your sovereign, and whatever you do should be done in a spirit of utmost fealty to him; His Majesty is also your father, and whatever you do should be done in a spirit of utmost filial piety towards him. Utter loyalty and utter filial piety will provide a stable basis for your life and make you renowned for your accomplishments.” Li Tai remarked, “I now understand the principles of fealty and filial piety, but I venture to ask how to apply the principles in practice.” Wang Gui replied, “In the Eastern Han period (25-220), Liu Cang, Prince of Dongping 东平王刘苍 [d. 83] said, ‘To do a good deed is the greatest joy’; I hope you will bear this in mind.” When the Emperor heard about this, he said joyfully, “My son may be able to avoid making too many mistakes.”’

Detail of watercolour miniature from ‘Tob be hūwašabure nirugan suhe gisun-i bithe’

The costume, accoutrements and furnishings in the watercolour illustration that accompanies this tale are anachronistic, being of the Ming period (1368-1644) rather than the Tang (618-907), which is when the story takes place. The Imperial Tutor stands in front of a desk with his hands clasped in greeting; his royal pupil reciprocates, while an attendant stands in the left foreground. Behind the tutor is a typical Ming style desk with plain dowel legs, a flanged apron and high stretchers. On the desk lie the familiar implements of the scholar, including the ‘four treasures of the literary studio’ (wen fang si bao 文房四宝), a sheet of paper (held down by two paperweights), a brush-pot containing writing brushes, an inkstone and a water-pot for moistening the stick of ink (concealed by the tutor’s body). A chair of the so-called lohan 罗汉 style typical of the Ming stands in front of a large screen decorated with a monochrome landscape painting depicting a body of water overhung by trees, with mist-enshrouded hills in the background. The small table in the top left-hand corner, like the desk in typical Ming style, is laden with books wrapped in covers of varied colours, bearing their titles on paper labels. The inscription in the top right-hand corner reads Tondo hiyoošun-i sain be sebjen obuha (‘Fealty and filial piety are a source of joy’).

While Jiao Hong’s scholarship was evidently of lasting importance, his career was subjected to repeated setbacks. Despite being a precocious child, he failed at his first attempt to take his bachelor’s degree in 1558, when aged 19. He succeeded on the second attempt five years later, only to experience further difficulties with his master’s degree: between 1565 (aged 26) and 1586 (aged 47), he failed the triennial examination eight times, finally passing at his ninth attempt in 1589 (aged 50). That same year, he proceeded to his doctorate, coming out first and becoming a zhuangyuan 状元 or optimus, one of only 89 in the entire 276 years of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

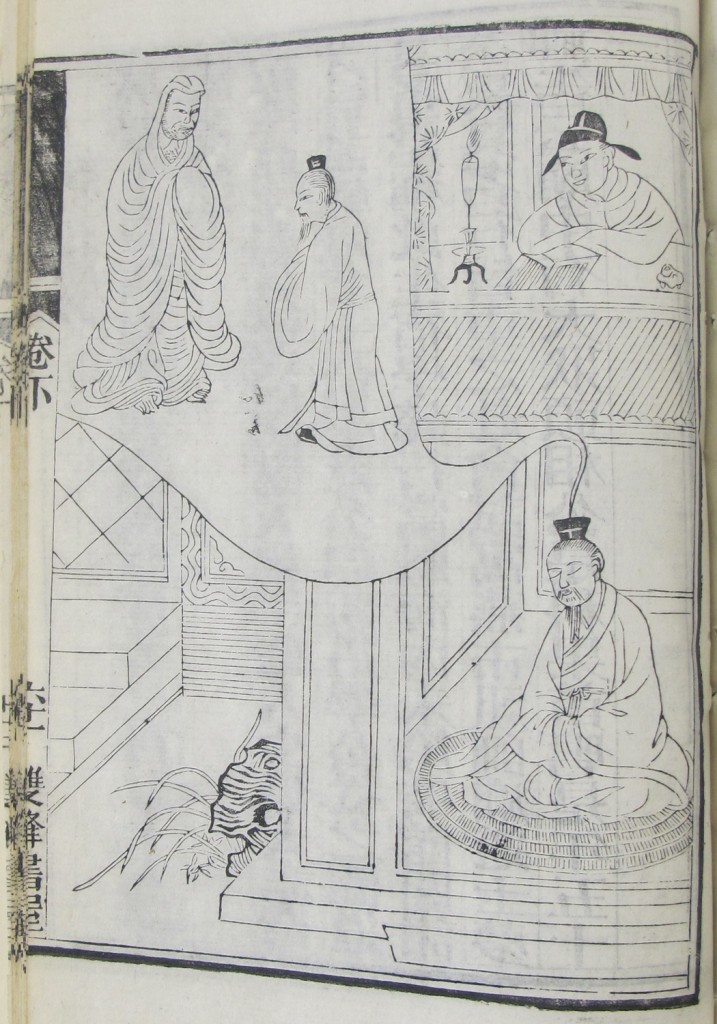

Woodcut of Jiao Hong working and the vision of a Daoist priest, from ‘Ming zhuang yuan tu kao’; 1876, FC.355.1

Woodcut of Jiao Hong working and the vision of a Daoist priest, from ‘Ming zhuang yuan tu kao’; 1876, FC.355.1

This woodcut, taken from Ming zhuang yuan tu kao 明状元图考, a xylographic printed book dated 1876, shows the indefatigable candidate burning the midnight oil in an upper room of the Daoist temple in Beijing where he was staying whilst taking the examinations in 1589. In the lower storey a meditating Daoist priest has a vision of himself in the presence of a spirit who foretells the success of Jiao Hong.

Jiao Hong’s accomplishments were hard-won – and unfortunately he encountered further difficulties at the imperial court. The publication of Yang zheng tu jie and his closeness to the throne through his tutorship of the Heir Apparent aroused his court rivals’ jealousy and enmity. Faced with accusations of financial impropriety, he was forced out of his post. Evidently resilient and determined, he nonetheless went on to become a prolific author: he has been credited with no fewer than fifty-six works, including notable editions of the Daoist classics Lao zi 老子 and Zhuang zi 庄子.

– Charles Aylmer, Head of the Chinese Department

Totally interesting in all my years never came across inner court text books of such either Zhuan Cao Zi style to Sanskrit or even Mongolian writings. Certainly not Japanese in all their attempts to control the courts of China since the Tang Dynasty resorting to being pirates over islands such as Taiwan in Independence. Perhaps the legacy of the first Emperor Hung Wu in the Ming Dynasty had resolved in preferring his first spouse of Muslim nomadic lineage to be his most liked in rebellion and conquest of country under fervent nationalism against mongrel rule from the north. Yet again still stayed firm to accept Muslim minorities in court and country over one near enough two thousand years in expended travel without any laws suggesting there was native Americanism Style Genocide as interpreted by the Western supreme powers in colonialisation theory as aired in American historical research over Native American Genocide over their Cavalry of recorded wars recorded in the past undoubtedly under the influence of their own cultured race race distinction and non Christian faith supremacy in its origins.

Fascinating and must find out more whether text is actually earthly Ming period or of Manchurian inner court decent from again a Korean bordered nomadic existance likewise the modern Korean sandwich Burger language of today depuis 1949.

A very posthumous collection of faith.