Silks, pearls and manuscripts

On the wall of the Library’s fourth floor of landing hangs a portrait of a man dressed in a very fine silk or satin doublet with an intricately woven lace collar. Over the top of the doublet is a long string of pearls, looped several times, to show them off to the best advantage.

The 1st Duke of Buckingham, by M. J. van Mierevelt, painted in 1625

This portrait was painted in 1625 by Michiel Janszoon van Mierevelt and the subject is George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, favourite of two Kings of England, James I and Charles I. Mierevelt (1566-1641) was a native of Delft, a lesser-known painter of the Dutch Golden Age. He is best known for his still life paintings, also for portraits for which he received many commissions, including some from royalty.

The Duke of Buckingham was a very handsome and charming man, keen to show off his wealth and power through his finery. He was born in 1592, into a family of modest means but with a mother with great ambitions for her son. She ensured he received a good education both in England and France, where he learned fencing, dancing and riding with the aim of forging a career at court.

In 1611 he met James I and soon became his firm favourite. In 1613, James made him gentleman of the bedchamber, later he was knighted, and subsequently enjoyed a meteoric rise to power, created Earl, then Marquess and eventually Duke of Buckingham in 1623. During his rise to power he purchased land and property including York House in London. Situated on the Thames, and later renamed Buckingham House, it was in York House that he displayed his magnificent pictures and other artistic works of which he amassed a large and valuable collection. As well as paintings, his interests included sculpture, also books and manuscripts, and any sort of curious object from all over the world. Objects suitable for such a collection were gradually becoming easier to acquire as a result of the expansion of international trading ventures.

Buckingham was also deeply immersed in the political and diplomatic affairs of the day, also becoming a firm friend of Charles, Prince of Wales, later King Charles I. In 1623 he accompanied Charles on a visit to Spain to negotiate the marriage of the Prince to the Spanish Infanta. Buckingham was deeply impressed by the equestrian portrait of King Charles V, the King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor, painted by Titian and commissioned a copy of it for York House in London. The marriage plans came to naught but both Charles and Buckingham greatly admired the art collections they saw in Madrid.

In 1625, Buckingham was in Paris in connection with further marriage negotiations – this time successful – between Prince Charles and the French Princess Henrietta Maria and it was here he probably met Rubens (1577-1640), already a distinguished painter with whom Buckingham also became friends. Rubens was by this time a highly influential artist, also an accomplished portrait painter. Buckingham commissioned from him an equestrian portrait like the one of Charles V he had seen in Spain. A study of the head Rubens made for this portrait, but lost for many years, was rediscovered in 2017 in Pollok House in Glasgow. This portrait is unfinished, but also shows the Duke wearing a fine silk or satin doublet and his knight’s sash in blue silk.

1st Duke of Buckingham painted by Sir Peter Paul Rubens, around 1625

Rubens was also a very successful diplomat and working on behalf of the Spanish Hapsburgs on information gathering in Madrid, Paris, London and the Netherlands at the same time as his artistic activities. Rubens and Buckingham were both in Paris, London and the Netherlands at various times between 1625 and 1628 and the Rubens portrait could have been painted in any of these places. During 1625, the Duke was visiting The Hague to sign a treaty with Dutch and Danish representatives for their countries to ally them against the growing Hapsburg power in Europe, so perhaps it was during this same year the van Mierevelt portrait was painted (Mierevelt had registered as a member of the Guild of St Luke in The Hague in 1625). So the Duke, within the span of a very few years, had two portraits made, each by a distinguished artist, both providing examples of the Duke’s very conscious cultivation of his personal image through art.

But having portraits painted was not Buckingham’s only involvement during his time in The Hague as this was also when he bought, in a very timely manner, the collection of Arabic manuscripts formerly belonging to the Dutch scholar Thomas van Erpe (or Erpenius, as he is usually known). Why the Duke was particularly interested in these remains a mystery, but it was perhaps something else of an unusual and exotic nature which he could add to his ever-expanding art and artefact collection in York House.

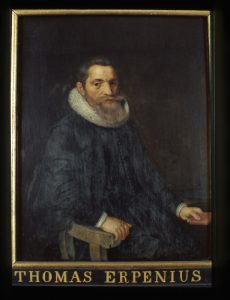

Thomas Erpenius, Professor of Arabic and Hebrew at the University of Leiden, 1613-24

Erpenius (1584-1624) was a Dutch orientalist, foremost in his field and famous for publishing the first accurate European grammar of Arabic, which remained in use as a textbook for scholars for several centuries. In 1613, he became Professor of Arabic in Leiden and in 1619, also Professor of Hebrew. In his travels around Europe (he never visited the Middle East) he amassed a collection of over eighty manuscripts from like-minded scholars.

In 1624, it is said after he caught the plague whilst translating diplomatic letters from Arabic, he died, leaving his manuscripts collection to be sold to the University. However, the Duke of Buckingham intervened in the negotiations with an offer of a cash payment of £500. This offer was accepted by the widow or Erpenius who was tired of the long bargaining procedures with the University of Leiden. The manuscripts were swiftly removed in secret to England, much to the confusion of those in Leiden.

But perhaps there was another reason behind the purchase of the Arabic manuscript collection. The Duke’s political career had begun to falter due to several unsuccessful military campaigns. Some blamed him for these failures and he began to lose some of his popularity. On the death of James I in 1625, it was thought he might lose royal patronage but, the Duke had always been a firm favourite with his successor, Charles I, since boyhood so his royal patronage continued unabated.

In 1626, King Charles I engineered the Duke’s election as Chancellor of the University of Cambridge, which the Duke gained by winning the vote by a very small majority. So perhaps the Erpenius manuscripts were purchased to strengthen his plan to be Chancellor at Cambridge, something not achieved at the time of their purchase but perhaps an ambition already discussed.

Charles I, like his friend the Duke, was also a great art collector and, during his reign amassed the greatest art collection ever collected by a reigning monarch. After his execution in 1649, this was sold off and widely dispersed, only to be reconstructed in 2018 in the Exhibition of his treasures at the Royal Academy.

Sir Thomas Adams, founder of the Cambridge chair of Arabic in 1632

Also a firm supporter of Charles I during his troubled reign, was Thomas Adams, a man born in Shropshire in 1586 and who had studied and Sidney Sussex College in Cambridge. Subsequently he forged a lucrative career as a draper in London, also a successful and busy career in public affairs, becoming Master of the Draper’s Company, MP for the City of London and later, in 1645-6, Lord Mayor. His unflagging loyalty to Charles I led to his arrest and imprisonment in the Tower where he was detained for some time. But on the restoration of the monarchy under Charles II in 1660, Sir Thomas was sent to the Netherlands to accompany the King home to London. He was later knighted, and, in 1661, made a Baronet.

However, it is not Adams’s political career which is most relevant to the story here, but his commercial career and with the import of fine fabrics from the Middle East and farther afield carried out by the ships of the Levant Company and the East India Company of which he became a freeman in 1641. The origins of such trade dates back to Italian commercial interests with Constantinople as early as the 15th century but the collapse of the Venetian Empire left opportunities for London merchants to reopen trade with the East. Petitions to Elizabeth I in 1580 resulted in a treaty with the Ottoman Empire leading to the foundation of the Levant Company in 1592 followed closely by the foundation of the East India Company in 1600.

Imported fine fabrics including silk and damask from the Middle East were much prized for their designs and delicacy. Both of the Duke’s portraits show the finery of his clothing and among members of the wealthy classes and the aristocracy these imported fabrics were greatly valued. Also imported were pearls which were fished in the Persian Gulf, both on the Arabian south shore, especially around Bahrain, and the northern, Persian, shore. These were also much prized, and the Duke is able to show off his beautiful strings of pearls in the Mierevelt portrait.

But Sir Thomas Adams had another important friendship and that was with Abraham Wheelock, like Adams, a native of Shropshire. He was a Cambridge scholar of both Anglo-Saxon and Arabic who had become the University Librarian in 1629. Wheelock was keen to develop Arabic teaching in the University. The surviving correspondence between Wheelock and Adams, held in the Library, indicate that Wheelock was forging a campaign to set up a lectureship in Arabic studies and that he was looking to Adams to find a sponsor. Adams, unable to find another supporter among his merchant friends, took on the responsibility himself, initially paying a stipend for three years but subsequently a permanent arrangement. The significance of this initiative to Adams and his trading fraternity was, of course, to develop the study of Arabic for use in the commercial world, unlike Wheelock, whose interests were of solely of an academic nature.

Wheelock, in Cambridge, was keen to develop a collection of manuscripts and books Arabic and other Middle Eastern languages both to support his teaching and to enhance the Library’s collections. It is unclear if Wheelock had any involvement in the purchase of the Erpenius manuscripts by the Duke several years earlier, but he knew of their existence and was very interested in their acquisition for the Library.

In 1628, the Duke’s misdeeds had eventually caught up with him and while in Portsmouth preparing for yet another political campaign on the Continent, he was stabbed to death by John Felton, a soldier with a grudge against him. After his death, the Duke’s complex financial affairs took several years to resolve and the manuscripts, now the property of his widow, the Duchess Katherine, lay ignored, much to Wheelock’s dismay.

But Wheelock was the driving force, along with Adams, behind the negotiations with the Duchess of Buckingham to acquire the manuscripts collection. He was well aware of its academic value and did all he could to hasten their arrival in Cambridge. Eventually the Duchess relented, and the manuscripts were sent to Cambridge in 1632, the very same year that Sir Thomas Adams founded at Cambridge, the first chair in Arabic in England, supported in perpetuity in his will. Both were triumphs of Wheelock’s quiet persistence.

So, through these intricate interactions between the artistic, political, commercial and academic worlds, brought about by personal connections or chance circumstances, often as a side-issue to unrelated intrigues, it is possible to trace the tangled story of the acquisition of the Library’s very first collection of Islamic manuscripts.

To return to the Duke and his story one last time, it is recorded that while visiting the French Court in 1624 to negotiate the marriage of Prince Charles to Henrietta Maria, he wore an impressive string of pearls so long that they reached to the ground. Are these the very same pearls displayed so well in the Mierevelt portrait? Who knows, but I would like to think that they are.

References

Mather, J. Pashas: traders and travelers in the Islamic world. New Haven, 2009

Oates, J.C.T. Cambridge University Library: a history. Vol. 1, from the beginnings to the Copyright Act of Queen Anne. Cambridge, 1986, pp. 163-7

Oates, J.C.T. Abraham Whelock, 1593-1653: orientalist, Anglo-Saxonist and University Librarian. Cambridge, 1966, pp. 39-49

Adams – Whelock correspondence. MS Dd.3.12. There is no known portrait of Whelock.

Excellent. Full of info and well written.