Dirt, Dust and Dodgy Joists, or, Memoirs of a Determined Archivist

In the last few days I’ve seen quite a bit of discussion on Twitter about the alleged erasure of the role of the archivist and librarian in the ‘discovery’ of documents. This follows on from a similar discussion I spotted last October. At that point I tweeted a couple of photos of archives in their pre-archivist state that proved very popular. I think it’s a good time to expand on that tweet a little and talk – personally and subjectively – about how some archives are found before being transferred to a repository. As an archivist I know that most collections don’t arrive neatly organised, clean and catalogued! This is something that perhaps some researchers don’t realise – or at least don’t know the full extent of it. I’ve enjoyed digging out a few more photos from previous jobs to illustrate the reality. These photographs show conditions that are not in any way uncommon….

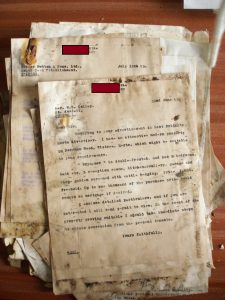

Over the years I have scrambled and crawled around a number of attics, cellars, basements and disused buildings to extract records that may become archives. In some cases I’ve scooped letters, photos and diaries off filthy floors into binbags in order to get them out before building work starts. Hard hats and torches have occasionally been involved. Believe me, the beige cardigans we’re characterised as wearing make a lot of sense in these circumstances!

Records in this condition are a very sad sight. I’ve seen what are clearly footprints on nineteenth-century hospital registers. I’ve come across desiccated biscuits and mummified mice. Something I’ll definitely never forget is the maggoty dead bird in a church in rural Herefordshire. More disturbingly, there can be other substances that remain forever unidentified. (Disconcertingly, sometimes movement can be spotted in binbags after you’ve filled them.) Of course there are always the ubiquitous rusted metal staples, paperclips and pins, dried rubber bands and tatty old pink tape. We remove all these #archivenasties so that users don’t have to!

To me, this is all part of the joy of the profession. I get much more satisfaction from dealing with a binbag of filthy, mixed up documents than simply transferring information from already well described and sorted records. Rummaging through one of these binbags, or a box or a trunk, really is like looking for treasure. The records are in no condition at this stage to be seen by researchers and maybe this is why our users don’t always know about the huge amount of work, professional skill and effort put into making these records available. We pride ourselves on producing beautifully clean and tidy archives (mostly!) but perhaps we should be more communicative about their previous state.

It’s not all about dealing with dirt, of course. Archivists have an extraordinary breadth and depth of knowledge that allows us to identify records of any age and to use the appropriate description so that they can be detected by researchers. Another vital skill is the ability to appraise and select appropriately – and there are all sorts of interesting discussions around this topic that are far too wide-ranging to fit into this post.

As for how things come to us in this state – well, it can be any number of reasons. People die and their relatives contact an archive service, a business closes down, a hospital moves to a new building, solicitors want to make some space. I’ve been contacted by administrative staff who simply don’t like the idea of throwing away ‘the old stuff’. We might go out to survey the records and find the accumulation of centuries, or mere decades. The most heartwarming rescue for me was some sixteenth-century town records discovered (in the truest sense) by some workmen clearing out a basement of a council building. They chose not to throw them away with the rest of the detritus and took them back to the depot. I was asked to go and look at them and realised that it was a hugely significant find. According to a printed history of the town those records had been missing since the early 1700s. There is no doubt that the people who should take the credit for that ‘discovery’ is those two men, who had no idea what they had saved but made the crucial decision to keep them.

I think that’s a good note on which to end. Don’t just recognise the archivists and librarians (although thank you for doing so!) – please acknowledge the role of the clerks, secretaries, cleaners, managers, workmen, relatives, interested people, and many others, who over the years made decisions not to throw records away, to put them in a secure, safe place, or to alert an archive service. Or thank the accident of fate that allowed some archives to lie forgotten and ignored until someone spotted their potential. I appreciate all the researchers – whether they be family historians, local and community historians or academics – who discover significance in the documents I help to care for and shine a (metaphorical) spotlight on them. And lastly – but absolutely not least – we should acknowledge our fabulous conservators, who so often bring documents back from the brink of disintegration or stabilise them enough to allow access. It truly takes a village to preserve, make available and exploit for research each and every archival document. Let’s all continue doing our bit with mutual respect to showcase these amazing survivors of so many tribulations!

Medieval title deeds waiting to be sorted, catalogued and assessed for conservation requirements

Pingback: Historical Highlights 142

As you state, lot of acknowledgement and awareness needs to be recognized to

Workmen who clear out buildings.

This is an ongoing process too at Montrose Air Station Heritage Museum, Broomfield Road, Montrose. See the web site