Despised, Adored and Often Ignored: school poetry anthologies and the trace of classrooms past

This post is by Julie Blake, a PhD student in the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge, currently finishing her thesis on the nature of poetry determined for GCSE English Literature from 1988 to 2018. Julie was shortlisted for the 2018 Rose Book-Collecting Prize and our new Entrance Hall exhibition tells the story of her research and collecting.

English-language school poetry anthologies have been part of the classroom since the beginning of mass education in the 19th century, but their history has not been told. My doctorate begins to tell it by looking at 100 poetry books used for GCSE English Literature in England since 1988. These are often cheap, low status and ephemeral books – most of the items in my collection cost 1p from online used booksellers. They are often annotated with student notes or the names of football clubs; pages are indented with rubbed-out pencil or the illustrations coloured in; school bookplates attest to the presence of children who might now be grandparents. In this blogpost I will discuss a few examples of the traces of classrooms past. These have the power to evoke our own memories of poetry at school, and they bear witness to changing ideas about young people and what they should be doing in school.

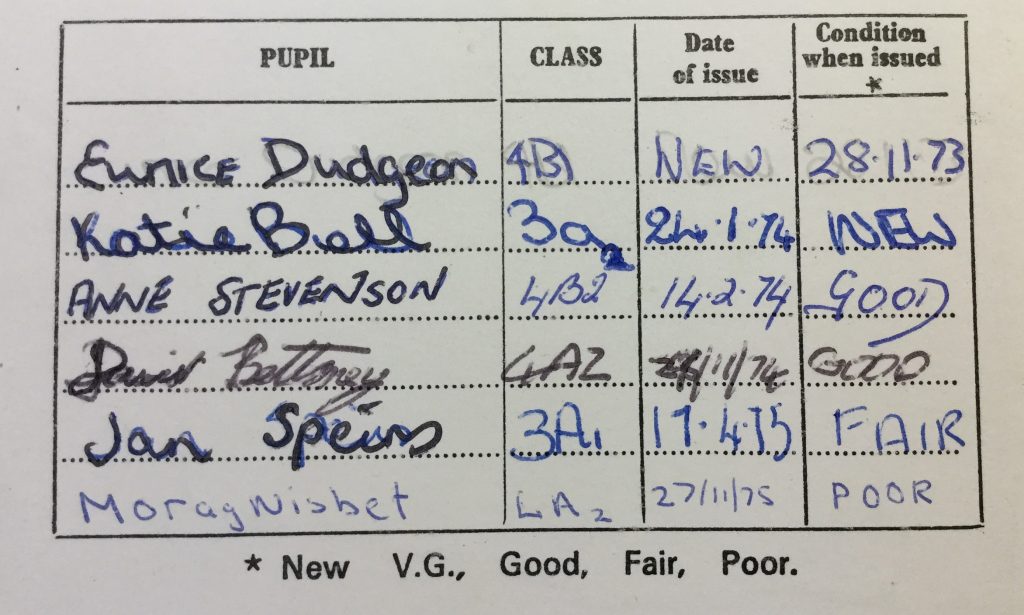

The first example (left) shows how schools issued textbooks to pupils at school in the 1970s using an adhesive bookplate. Pupils signed and dated their borrowing of the book so that they could take it home to read. Where I taught some decades later books were also marked with a school stamp and a book number, and we logged pupil names and numbers on a sheet no-one ever looked at again. It was a pleasant if mildly chaotic ritual. This sticker tells us the book was allocated to pupils for a relatively short time, perhaps an enjoyable little scheme of work on the “Creatures” cluster of poems. The pupils were asked to state the condition of the book when they received it, presumably to make them accountable for any damage, but the sticker also gives us a glimpse of the offbeat ways teenagers survive such futile bureaucracy: over two years, six pupils solemnly swear to the book’s decline from “NEW” to “POOR” when it is in fact entirely unmarked and, apart from slightly scuffed edges to the cover, in excellent condition. Looking at their distinctive individual signatures now, I can’t help but wonder what happened to Eunice, Katie, Anne, David, Jan and Morag of Grange Academy in Ayr.

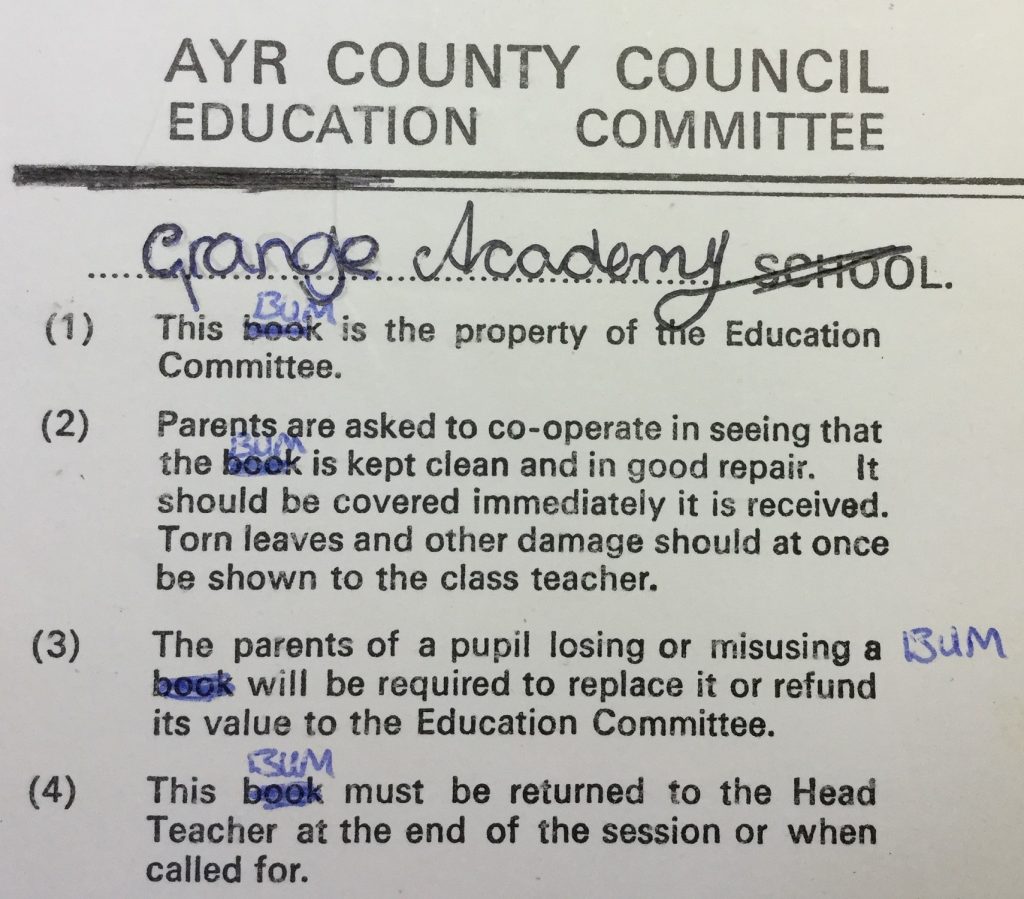

Eunice and her schoolmates appear on the lower half of the bookplate. The top half (right) asserts the local Education Committee’s ownership of the book and their rights over it, as well as parent and pupil responsibilities for covering it, keeping it clean, reporting damage, recompensing loss or damage and returning the book when required. Every time the word “book” is used, a mischievous pupil (I suspect Morag Nisbet…) has neatly crossed it out and replaced it with the word “bum”. This kind of daft humour is one of the many things I miss about teaching adolescents. The second example of students making their mark (below) comes from the cover of Poets of Our Time, first published in 1965 but still going strong in 1982 when I had the misfortune to study it for O Level English Literature. Our copies had a plain white cover not the gloriously psychedelic blue one that Mark French and Terry Rush signed out at Addey and Stanhope School in New Cross Road, London SE14. I wonder whether it was Mark or Terry who so carefully embellished the cover design with 20 or more carefully interlaced iterations of the word “Millwall”, a local football club. They also inscribed “Front of poetry book”, a useful orientation on a wordless jacket and when the school bookplate has been stuck upside down on the rear inside cover!

Eunice and her schoolmates appear on the lower half of the bookplate. The top half (right) asserts the local Education Committee’s ownership of the book and their rights over it, as well as parent and pupil responsibilities for covering it, keeping it clean, reporting damage, recompensing loss or damage and returning the book when required. Every time the word “book” is used, a mischievous pupil (I suspect Morag Nisbet…) has neatly crossed it out and replaced it with the word “bum”. This kind of daft humour is one of the many things I miss about teaching adolescents. The second example of students making their mark (below) comes from the cover of Poets of Our Time, first published in 1965 but still going strong in 1982 when I had the misfortune to study it for O Level English Literature. Our copies had a plain white cover not the gloriously psychedelic blue one that Mark French and Terry Rush signed out at Addey and Stanhope School in New Cross Road, London SE14. I wonder whether it was Mark or Terry who so carefully embellished the cover design with 20 or more carefully interlaced iterations of the word “Millwall”, a local football club. They also inscribed “Front of poetry book”, a useful orientation on a wordless jacket and when the school bookplate has been stuck upside down on the rear inside cover!

Inside, their annotation of Clifford Dyment’s poem ‘Coming of the Fog’ is enhanced by “Led Zep” (also just “Led”) and “Yes” (twice), names of two popular 1970s rock bands, in the fashionable bubble writing of album cover artwork. Vandalism of the kind sternly warned against by Ayr Local Education Committee? A sign of offbeat engagement with the line “I range in the mind”, or a re-supply of semiotic interest to a poem that has been presented to a 15 year old boy as a linguistic skeleton (Ben Rampton’s 2006 Language in Late Modernity contains a brilliant discussion of related examples of this occurring in more recent London schools). We can’t know for sure what was going on, but we can certainly feel the traces of teenage boredom, wit and enjoyment of their own cultural practices beyond the classroom.

Inside, their annotation of Clifford Dyment’s poem ‘Coming of the Fog’ is enhanced by “Led Zep” (also just “Led”) and “Yes” (twice), names of two popular 1970s rock bands, in the fashionable bubble writing of album cover artwork. Vandalism of the kind sternly warned against by Ayr Local Education Committee? A sign of offbeat engagement with the line “I range in the mind”, or a re-supply of semiotic interest to a poem that has been presented to a 15 year old boy as a linguistic skeleton (Ben Rampton’s 2006 Language in Late Modernity contains a brilliant discussion of related examples of this occurring in more recent London schools). We can’t know for sure what was going on, but we can certainly feel the traces of teenage boredom, wit and enjoyment of their own cultural practices beyond the classroom.

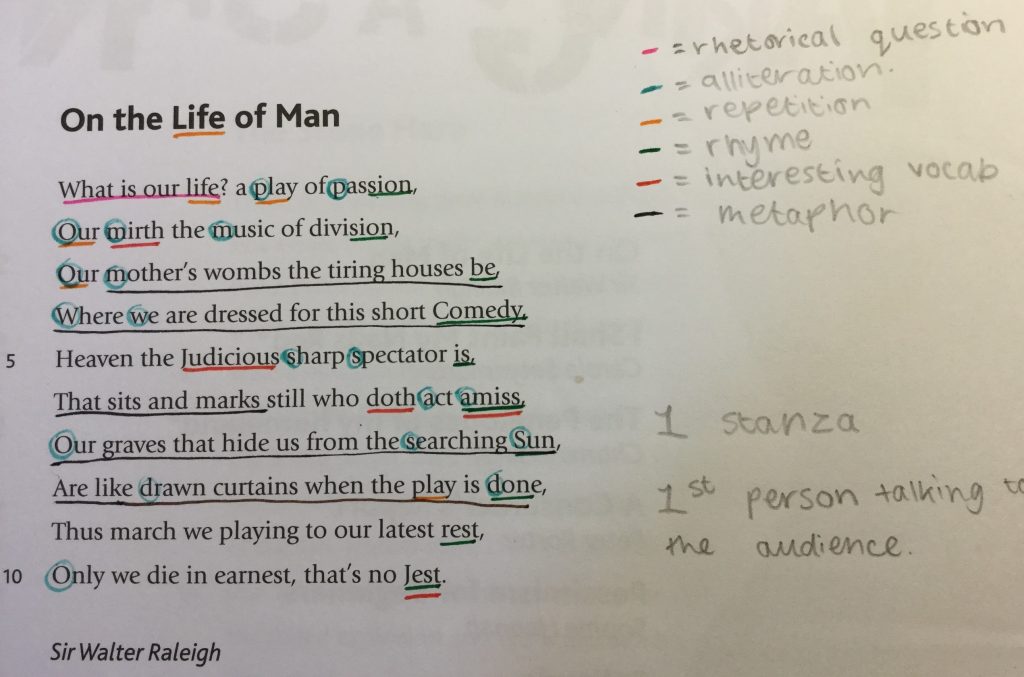

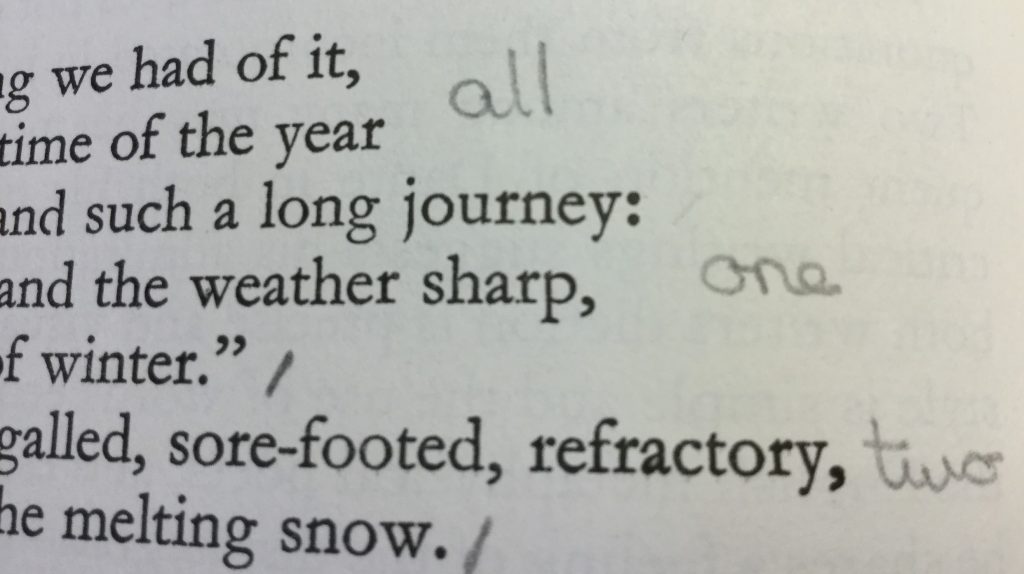

Mark and/or Terry had lots of things on their mind as they annotated Dyment’s poem in class. There is a warm fuzziness to their serious annotations and youthful life in their playful ones. There is neither in the regimented annotations of the unknown student in the 2009 Edexcel GCSE Poetry Anthology (left). Instead there is a six colour coding system that obliterates the poem and atomises it into a series of structural features. The word “doth” can only be “interesting vocab” if a teacher has told you an examiner might like it and there is no sense here of engagement with the sonic patterning of the poem or the movement of its thoughts. The student who wrote in Maurice Wollman’s 1957 Ten Twentieth Century Poets (below) tells us so much more about their engagement with the poem through the almost-forgotten classroom practice of choral recitation. The words “all”, “one”, “two” and “three” jotted around the poem show the pupils imagining that the wise men of T.S. Eliot’s poem ‘The Journey of the Magi’ take turns speaking, and sometimes speak together, to recount their experience. They have allocated the roles of Magi 1, 2 and 3 to themselves and decided who will speak which lines, using short diagonal pencil marks to delineate the boundaries of their turns. They were probably also directed by their teacher to consider pace, rhythm and volume in preparing their performance, perhaps a lesson activity, perhaps part of a Christmas event in school. I’ll wager these pupils of Shire Oak School learned far more about poetry by doing this than the poor benighted pupil with their highlighter pen.

Mark and/or Terry had lots of things on their mind as they annotated Dyment’s poem in class. There is a warm fuzziness to their serious annotations and youthful life in their playful ones. There is neither in the regimented annotations of the unknown student in the 2009 Edexcel GCSE Poetry Anthology (left). Instead there is a six colour coding system that obliterates the poem and atomises it into a series of structural features. The word “doth” can only be “interesting vocab” if a teacher has told you an examiner might like it and there is no sense here of engagement with the sonic patterning of the poem or the movement of its thoughts. The student who wrote in Maurice Wollman’s 1957 Ten Twentieth Century Poets (below) tells us so much more about their engagement with the poem through the almost-forgotten classroom practice of choral recitation. The words “all”, “one”, “two” and “three” jotted around the poem show the pupils imagining that the wise men of T.S. Eliot’s poem ‘The Journey of the Magi’ take turns speaking, and sometimes speak together, to recount their experience. They have allocated the roles of Magi 1, 2 and 3 to themselves and decided who will speak which lines, using short diagonal pencil marks to delineate the boundaries of their turns. They were probably also directed by their teacher to consider pace, rhythm and volume in preparing their performance, perhaps a lesson activity, perhaps part of a Christmas event in school. I’ll wager these pupils of Shire Oak School learned far more about poetry by doing this than the poor benighted pupil with their highlighter pen.

Despised, adored or ignored, used school poetry anthologies have lots to tell us about what young people are up to when we think we’re teaching them poetry. All I remember is our English teacher’s far more interesting stories of the bands he’d reviewed for New Musical Express. It’s a wonder I’m here at all…

Despised, adored or ignored, used school poetry anthologies have lots to tell us about what young people are up to when we think we’re teaching them poetry. All I remember is our English teacher’s far more interesting stories of the bands he’d reviewed for New Musical Express. It’s a wonder I’m here at all…

Julie’s exhibition will be up until Saturday 2nd February, during normal opening hours. Contact Julie (jb917@cam.ac.uk) for further information. Places are still available at her talk on Wednesday 16th January (5.00-6.30); see our website for more information and to book.

So evocative !! I think the Nisbet annotations should be preserved at the British Library and perhaps will be shown centuries hence like the Monks schedulae – notes in manuscripts !!!