Challenging Challenger: The Fallout between Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and the Society for Psychical Research

Post by Elizabeth Savage, PhD (Dunelm)

“Do you conceive that a logical brain, a brain of the first order, needs to read and to study before it can detect a manifest absurdity? Am I to study mathematics in order to confute the man who tells me that two and two are five? Must I study physics once more and take down my Principia because some rogue or fool insists that a table can rise in the air against the law of gravity? Does it take five hundred volumes to inform us of a thing which is proved in every police-court when an impostor is exposed? Enid, I am ashamed of you!”[1]

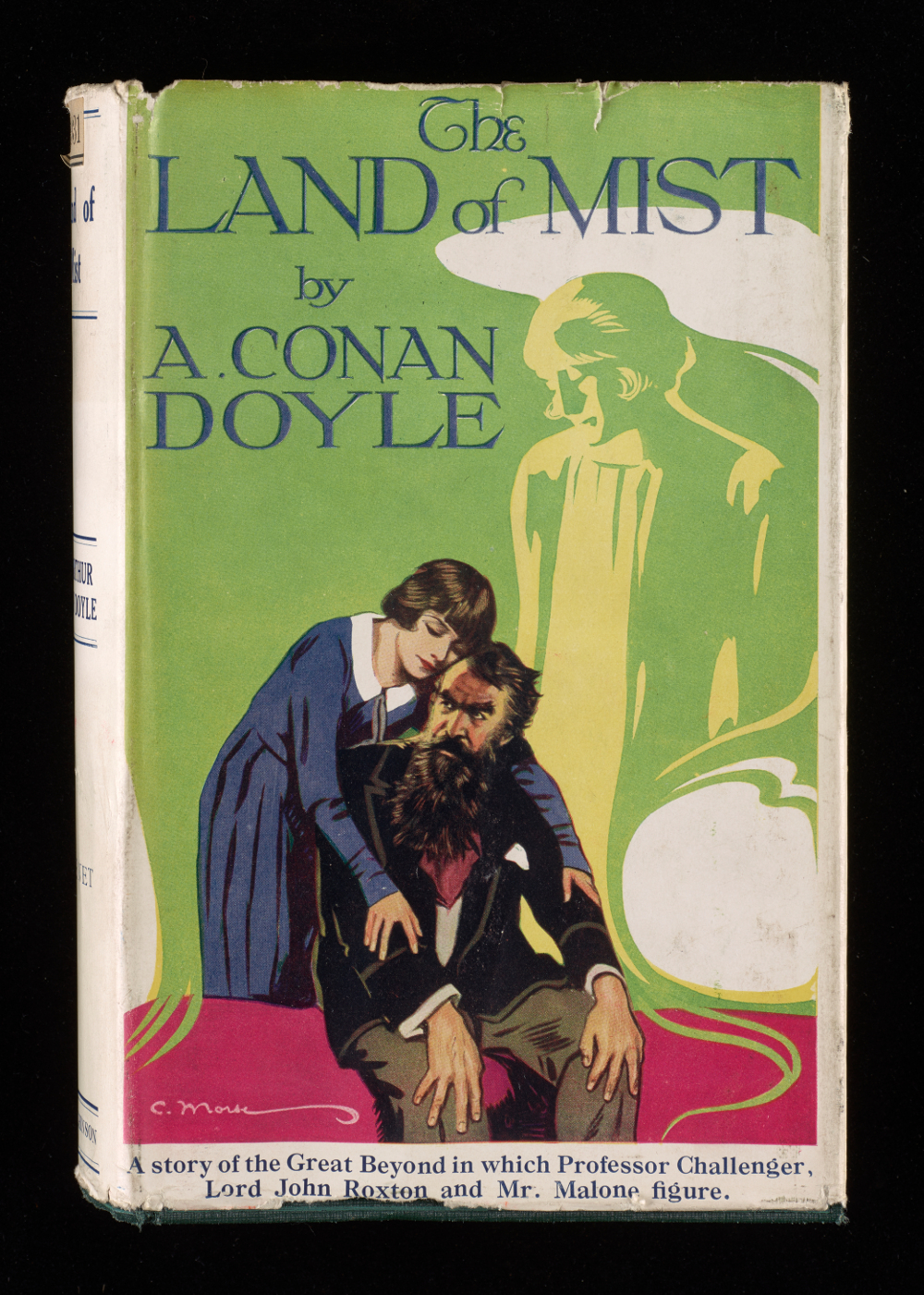

Published in 1926, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Land of Mist sees the intrepid Professor Challenger, first introduced to readers in The Lost World, as a sceptic – psychical phenomena, to him, is absurd as is anyone and anything associated with the subject. This seems an odd turn for a character that has in previous adventures cavorted with dinosaurs and ‘poisonous’ ethers threatening to wreak havoc on the earth. But then, if Conan Doyle didn’t make Challenger a sceptic in the beginning, would the ending of The Land of Mist pack the same punch? With the risk of sounding horribly ‘punny’, Conan Doyle needed to challenge Challenger – and win.

Between a box of ectoplasm and album of spirit photography, tucked away with reports concerning the Enfield Poltergeist and Borley Rectory, you can find Conan Doyle’s indelible mark on the Society for Psychical Research at Cambridge University Library. The Library holds on deposit a large expanse of material from the SPR archives dating from its inception in 1882 to the late 1990s and beyond. This, of course, includes Conan Doyle’s own work – and his resignation letter. And its public fall out. (And, yes, ectoplasm – but that’s for another day.)

Conan Doyle had joined the SPR in 1893, though his interest in Spiritualism and psychical phenomena had begun in the late 1880s. With fame secured thanks to a certain fictional detective, the world saw his beliefs – not to mention his grief – deepen significantly with the deaths of his son, brother, and nephews during and after the first World War. From his relationship with Houdini to the automatic writings of his children’s nanny to the famous Cottingley Fairies, Conan Doyle became a high-profile Spiritualist who, much like The X-Files’ Fox Mulder, wanted to believe and who, to some, was perhaps too eager to do so.

‘There is nothing more wonderful, more incredible,’ Conan Doyle wrote in his essay ‘The Shadows on the Screen’ (1920), ‘and, at the same time, as it seems to me, more certain, than that past events may leave a record upon our surroundings which is capable of making itself felt, heard, or seen for a long time afterwards.’ [2] Life after death was one of Conan Doyle’s main preoccupations – something he made part of Challenger’s story, in fact. In The Land of Mist, Challenger admits to hearing what sounded like his dead wife’s knock upon a door, but dismisses it as the effects of grief. ‘I saw how even a clever man could be deceived by his own emotions,’ says Challenger.[3] Now if we look at the language Conan Doyle uses in his essay – ‘wonderful’, ‘incredible’, ‘certain’ – we encounter a similarly emotional, but far less sceptical, response to the idea of life after death. Conan Doyle does count himself as someone deceived by his own emotions and, as we see, he uses his belief as a basis for his own psychical research. In other words: he has Mulder’s sense of hope. Conan Doyle also believed in following ‘the true scientific fashion,’ as he states in ‘The Law of the Ghost’ (1919), and ‘following the facts wherever they lead without any preliminary prejudice’ but he began to note even then that ‘it is unfortunately one which has been neglected by most scientific men in approaching this new subject which would not fit in with their preconceived ideas.’[4] And it was this notion of preconceived ideas that ultimately led to the split between Conan Doyle and the SPR – a split that in many ways ran parallel to Challenger’s own challenge.

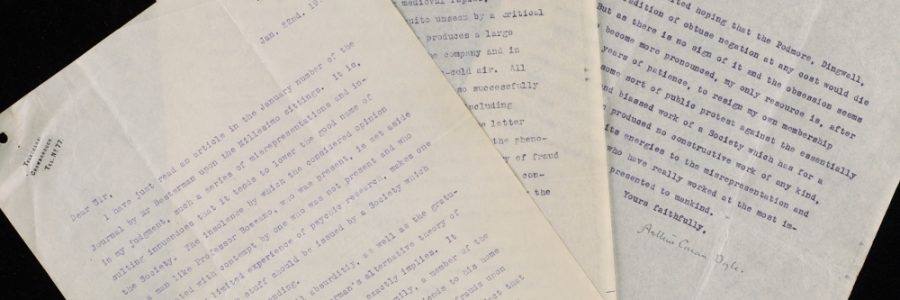

Conan Doyle called it a ‘tradition of obtuse negation’. In 1930, the author was ill – and angry. A review had appeared in the SPR Journal by Theodore Besterman that claimed a series of sittings with an Italian medium were fraudulent. ‘To appreciate the full absurdity,’ Conan Doyle writes in his resignation letter dated 22 January 1930, ‘as well as the gratuitous offensiveness of Mr Besterman’s alternative theory of fraud, one has to visualise what it exactly implies. […] Can we dignify such nonsense as this by the name of Psychic Research, or is it not the limit of puerile perversity?’[5] Conan Doyle thought that Besterman was reaching. He believed the reported phenomena could not be so easily written off or explained as Besterman had – not to mention the fact that Besterman hadn’t even been present for the sittings. But perhaps what bothered Conan Doyle most was what he saw as an increasingly sceptic approach overall to the SPR’s research in general. He writes in his resignation that the ‘assertions of the opponents of Spiritualism are at once accepted on their face value without the slightest attempt at discriminate examination.’[6] To Conan Doyle, the SPR worked only to disprove and negate.

‘[…] my only resource is, after thirty-six years of patience, to resign my own membership and to make some sort of public protest against the essentially unscientific and biassed [sic] work of a Society which has for a whole generation produced no constructive work of any kind, but has confined its energies to the misrepresentation and hindrance of those who have really worked at the most important problem ever presented to mankind.

Yours faithfully,

Arthur Conan Doyle’[7]

Conan Doyle’s letter shook the SPR. In archival material here in the Manuscripts Reading Room, you can see first-hand the back and forth between ranking members on how to respond and address the matter. ‘I am rather glad Sir A.C.D. is leaving us. He is rather a dangerous member to have!’ Eleanor Sidgwick wrote in a personal letter to W.H. Salter. [8] In another letter written to the Chairman of the Council at the SPR, Stanley DeBrath, argues that ‘Sir Arthur is in weak health and has allowed the critique of Mrs Kelly Hack’s book to make far too much impression on his mind.’[9]

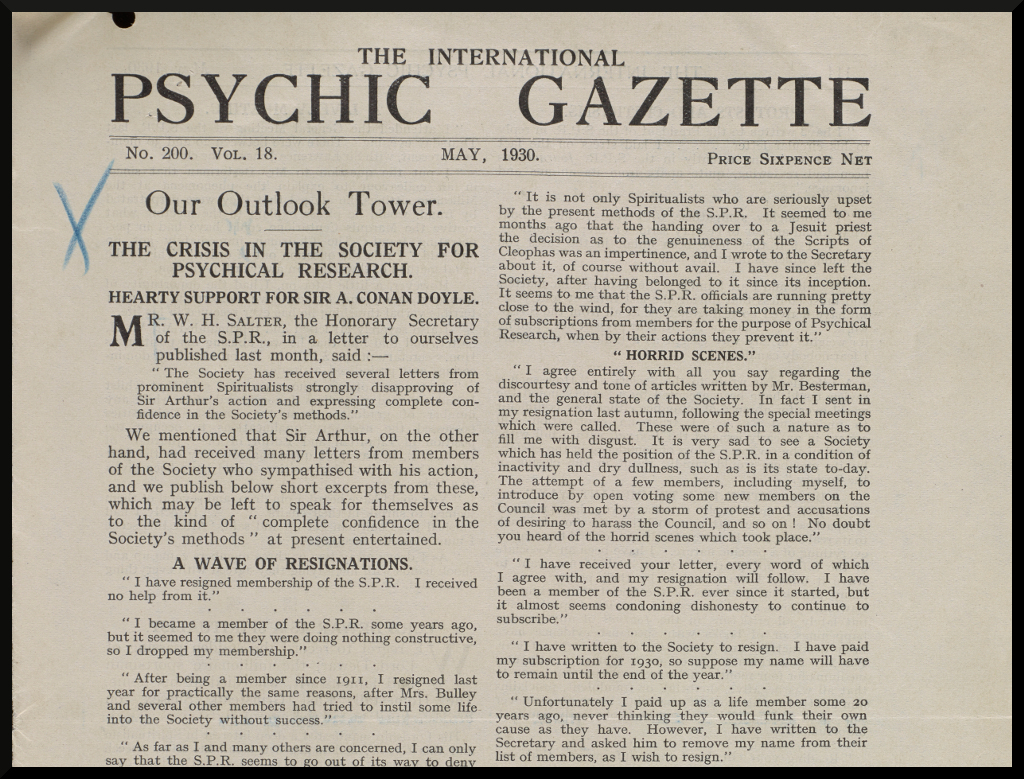

The May 1930 issue of the International Psychic Gazette printed a barrage of quotations under the headline ‘The Crisis in the Society for Psychical Research. Hearty Support for Sir A. Conan Doyle.’[10] Theodore Besterman responded to Conan Doyle’s criticism in a circular stating ‘I have learned that the S.P.R. is concerned not with opinions but with facts […]. If […] Sir Arthur Conan Doyle consider[s] my conclusions inaccurate, let [him] put forward facts, not opinions, to refute them.’[11] The SPR’s president challenged Conan Doyle’s belief that the Society had not produced constructive work for years and touched upon Spiritualism: ‘It has been one of the great achievements of the Society that it has always comprised among its active and loyal members persons whose view on Spiritualism range from complete acceptance to total denial: this has only been possible because an atmosphere of toleration combined with frank mutual criticism has been congenial to most of its members.’[12]

Whether there is life after death, whether mediums and spirit photography are hoaxes or not doesn’t really matter here. It just isn’t what Conan Doyle and the SPR are butting heads over. Conan Doyle’s resignation is about the approach to research methodology – as is the SPR’s response both internally and externally. Yes, there are discussions of mediums and frauds and swords hidden beneath dresses, but the real focus is on the ways in which the investigators reached their conclusions. Their biases. Their beliefs. Their experience. Their emotions.

‘Good may, however, come out of evil if the effect of this debate should be a fresh orientation of the Society’s policy by which some more human and practical contact with spiritualists and especially mediums would be effected.

The work of the Society is bound to be sterile as long as they are cut off from the raw material of their study which is their position at present. To bring such better relations greater sympathy and less rigidity of thought are called for upon the part of the society.’[13]

If we then equate Professor Challenger to the SPR – or, rather, to how Conan Doyle perceived the SPR to be – we see the same challenge has been posed. Turn the sceptic to the sympathetic. Challenger, the rigid sceptic, becomes – through the events of The Land of Mist (séances and ghosts of dead wives and what have you) – the softened sympathetic student of psychical research. ‘With characteristic energy,’ Conan Doyle writes, ‘[Challenger] plunged into the wonderful literature of the subject, and […] without prejudice which had formerly darkened his brain […] he marvelled that he could ever for one instant have imagined that such a consensus of opinion could be founded upon error.’[14] While the description borders a bit on the comical, there is no doubt behind Conan Doyle’s meaning – it is the same thought expressed in his second letter to the SPR: ‘sympathy and less rigidity of thought are called upon’. We are told that Challenger becomes a ‘gentler, humbler, and more spiritual man.’[15] We are able to see what is perhaps an early vision of just how Conan Doyle imagined a fundamental change in methodology to be. Challenger can still very much be a scientist and burly adventurer, but it’s the approach to his research that changes. That, to Conan Doyle, makes the difference. And who better to demonstrate that ideological change than a character like Challenger?

The novel does not end with Challenger hunched over his books looking for proof of life after death, of course. No, it’s likely Challenger was off on another adventure by the time the narrative shifted from him. Instead, we are treated to a scene between his daughter Enid and her new husband in a moment that perhaps underlines the reason for Conan Doyle’s desire for sympathetic research, for hope and a want to believe.

‘One thing we have learned,’ said he. ‘It is that two souls, where real love exists, go on and on without a break through all the spheres. Why, then, should you and I fear death, or anything which life or death can bring?’

She smiled and put her hand in his.

‘Why indeed?’ said she.[16]

[1] Doyle, Arthur Conan, The Land of Mist (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1926), 14. (Classmark: 1926.7.931)

[2] Doyle, Arthur Conan, ‘The Shadows on the Screen’, The Edge of the Unknown (London: J. Murray, 1930), 63. (Classmark: 9180.d.749)

[3] Doyle, The Land of Mist, 17.

[4] Doyle, Arthur Conan, ‘The Law of the Ghost’, The Edge of the Unknown (London: J. Murray, 1930), 114. (Classmark: 9180.d.749)

[5] Letter from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to the SPR dated 22 January 1930. (Classmark: MS SPR/99/6/3/2)

[6] Letter from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to the SPR dated 22 January 1930.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Letter from Eleanor Sidgwick to W.H. Salter dated 25 January 1930. (Classmark: MS SPR/99/6/3/2)

[9] Letter from Stanley DeBrath to SPR Chairman of Council dated 18 February 1930. (Classmark: MS SPR/99/6/3/2)

[10] The International Psychic Gazette, No. 200, Vol. 18, May 1930 (Classmark: MS SPR/99/6/3/2)

[11] Circular from Theodore Besterman to the SPR dated 14 February 1930 (Classmark: MS SPR/99/6/3/2)

[12] Circular from Lawrence J. Jones to the SPR dated 14 February 1930 (Classmark: MS SPR/99/6/3/2)

[13] Letter from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to SPR dated 25 February 1930 (Classmark: MS SPR/99/6/3/2)

[14] Doyle, The Land of Mist, 281.

[15] Doyle, The Land of Mist, 281.

[16] Doyle, The Land of Mist, 285-6.

Great article! Just a note that the episode was long predated by similar disputes between SPR founders such as F.W.H. Myers and the Sidgwicks with ‘the other Darwin’, Alfred Russel Wallace, who was a rather uncritical spiritualist. In the 1880s Wallace and other spiritualists accused fellow SPR members of deliberately undermining supposed evidence for spiritualism by “explaining mediumship and apparitions in terms of psychological automatisms, hallucinations, and telepathy from the living”, and by presenting experimental evidence for the fallacy of eyewitness testimony. See https://www.forbiddenhistories.com/cambridge-collections for this and other early goodies from the SPR collection.