Digitisation of the Polonsky Foundation Greek Manuscripts Project: a reflection on digital technologies and collective memory

My name is Raffaella Losito, and in March 2020 I had the great privilege to join the Digital Content Unit team as a Digitisation Technician to work on the Polonsky Foundation Greek Manuscripts Project. In 2017 I completed my studies in Photography for Cultural Heritage at the ISIA of Urbino (Italy). Then I moved to the UK, where I started to work for different cultural institutions, including the Wellcome Collection, the British Library and the Ashmolean Museum. I’ve always been interested in how new media can interact with analogue productions, which brings me to reflect on digital technologies and their impact on the collective memory.

For the past few years, I have been involved in the digitisation process of several types of objects, including photographic negatives, drawings, paintings and loose documents, each one having its own character. What makes the Greek Manuscripts Project different from any project I’ve worked on previously is the remarkable scale of it. This project aims to digitise 443 Greek Manuscripts which reside in Cambridge University Library, the Fitzwilliam Museum and 12 Cambridge colleges, as well as a similar number of manuscripts in the Biblioteca Palatina in the Vatican Library.

I have to admit that the scale of the project sounded intimidating when I first heard of it. But on the other hand, I was excited, as I love challenges. After my induction week, I began photographing my first volume, and at that moment the magic began. When I am in the digitisation studio, with the manuscript lying on the cradle, under the solitary beam of a dim modelling light, I immediately establish a profound and intimate relationship with the object and its history. I can connect with the book through all my senses, feeling it as I gently open, hearing the sound of its micro-movements, touching those fragile pages as they turn and unveil its delicate scent.

The curators identified the books for the Greek Manuscripts Project a couple of years ago. My colleagues from conservation have looked at it during the past months and worked their magic to make it safe for digitisation. Then, the cataloguers will compare the images I am taking now against the volumes and will prepare the descriptions. Finally, it will be published on the Cambridge Digital Library to be accessible for research, teaching, learning, art, further publication and general appreciation. This is what I like the most about being a Cultural Heritage Photographer: the privilege of being part of the community of professionals who are looking after these precious objects and playing a crucial role in generating a new form of knowledge.

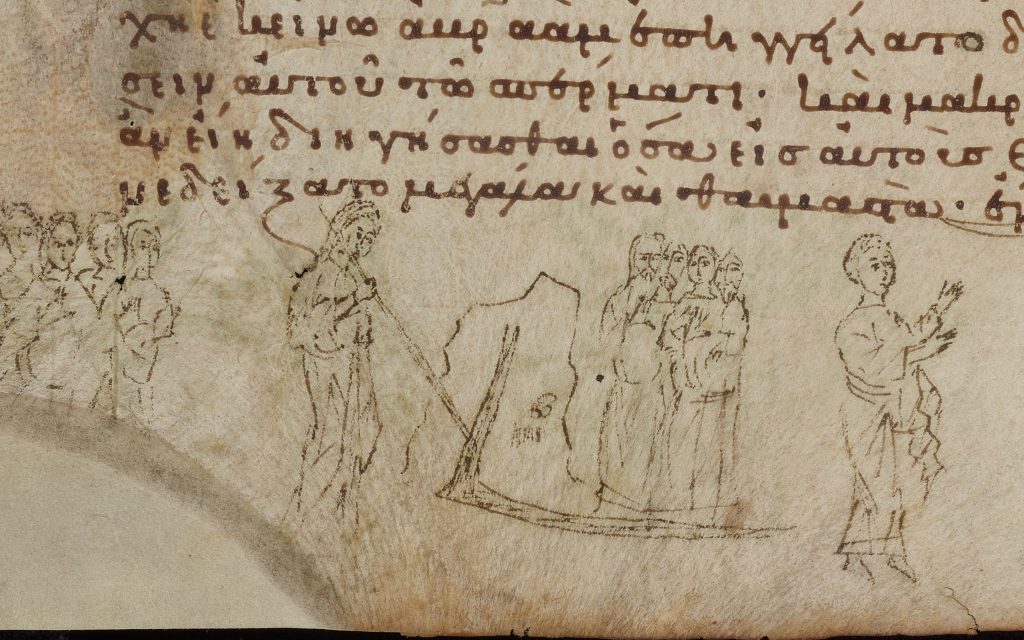

King’s College MS 45: Life of Barlaam and Joasaph is an exceptional manuscript already online (see https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-KINGS-00045/1). What interested me in this case is that this 12th-century manuscript offers us a good example of cultural stratification and it represents the overlapping of different cultures, a recurring feature of the Greek manuscripts collection.

Indeed, this manuscript transmits the Eastern concept of Buddhism to Western culture, by narrating a Christianised version of the life of the Buddha. In other words, we are seeing the end of a line of a succession of adoptions and alterations via Persian, Arabic and Georgian versions. These lead, in the 11th century, to the Greek translation of the story by Euthymios Hagioreites, a Georgian monk. Alongside the text, we can see a layer of illustrations appearing on 90 pages, portraying 134 different scenes. Interestingly, these illustrations start as simple drawings in ink and in the midst of the manuscript began to be completed with paint, suggesting that the artist broke off work in the course of the task and never returned to it. Also, rather than having a designated space on the page, these illustrations are fitted into the standard margins.

The different states of completeness of the illustrations in this manuscript offer us an ideal case study for the use of specialist photography such as multispectral imaging. I hope it might be possible to investigate this manuscript further. Taking advantage of non-invasive imaging techniques could help us to understand the object more deeply and to determine the pigments used or to reveal the underlying layers of the illustration.

It’s fascinating to think about how we intervene in the manuscripts’ timeline today, adding another layer to the intense cultural stratification which started centuries ago with scribes transcribing texts, using the technologies of their time. When creating an archival image, we are transcribing the nature of the object into a new technology. The digital surrogate represents the first stage of a new life for the object itself, that in the future could lead to fruitful new immersive contexts. In these future spaces, whose history is rooted in a primordial environment of paper and parchment, digital technologies offer a new continuity of memory. Reflecting on this reminds me of an interesting article a friend shared with me some time ago from the New York Times Magazine, by the Nigerian-American writer Teju Cole:

Photography is inescapably a memorial art. It selects, out of the flow of time, a moment to be preserved, with the moments before and after falling away like sheer cliffs. (..) Photography is about retention: not only the ability to make an image directly out of the interaction between light and the tangible world, but also the possibility of saving that image. A shadow thrown onto a wall is not photography. But if the wall is photosensitive and the shadow remains after the body has moved on, that is photography.

(..) When the photograph outlives the body — when people die, scenes change, trees grow or are chopped down — it becomes a memorial. And when the thing photographed is a work of art or architecture that has been destroyed, this effect is amplified even further. A painting, sculpture or temple, as a record of both human skill and emotion, is already a site of memory; when its only remaining trace is a photograph, that photograph becomes a memorial to a memory. Such a photograph is shadowed by its vanished ancestor.

This article has inspired me to interrogate the role of cultural heritage photography and its moral purpose in particular. We need to recognise that digitisation processes are becoming increasingly more important. It is not only a way of creating a digital surrogate of the original artwork and so reducing handling of the fragile object. It also changes our cultural experience. We are now able to study the object through an image that is the result of a meticulous imaging protocol, which aim to reproduce the colours consistently and correctly. Naturally, this is almost impossible for the human eye, in the variable lighting conditions of a reading room.

Moreover, digitisation both meets and stimulates demand from users, whether they are working in the same library or on the other side of the world. Digital files can facilitate new interpretations and understanding of the object itself, accelerating new types of collaboration between communities of students, academic researchers, artists, cultural heritage professionals and general public.

I think that now more than ever, we need these digital surrogates to fulfil our deep need to stop precious objects from disappearing from the woven threads of memory. At the exact moment we’re framing an everyday situation, we’re imprinting that moment in our memory by the act of digitising it. That is a way to reassure ourselves that nothing is ever really gone.

References:

Cole, Teju, ‘Memories of Things Unseen‘ New York Times Magazine (14 Oct 2015).

Geismar, Haidy, Museum Object Lessons for the Digital Age (London: UCL Press, 2018). Available for free download

MacDonald, Lindsay (ed) Digital Heritage. Applying Digital Imaging to Cultural Heritage (Amsterdam etc: Butterworth Heinemann/Elsevier, 2006).