A Curious Cure for a Cambridge Book – Part One

As one of the Project Cataloguers for Curious Cures in Cambridge Libraries, I feel incredibly lucky to be able to spend time with the diverse range of manuscripts that fall within the project’s remit. Many of these are medical textbooks and receptaria, of course, but the project also encompasses liturgical, legal, literary and commonplace books that contain medical recipes written into the margins or blank spaces around the text. One such manuscript is Cambridge, University Library, MS Add. 5368 (hereafter Add. 5368), a copy of the Homilies of Origen, produced in England in the late twelfth century.

Origen of Alexandria (c. 185–c. 253) was an early Christian theologian and a prolific writer. He is remembered for producing the first complete critical edition of the Hebrew Bible with parallel Greek text (the Hexapla), for his exegetical writings on Biblical texts, and for his contributions to theological discussions and debates. Origen’s writings were widely circulated during his own lifetime — and their popularity extended into western Europe in the Middle Ages thanks to another early Christian writer, Rufinus of Aquileia (c. 344/345–411). Origen had written his works in Greek and Rufinus brought many of them to a wider audience by translating them into Latin. Add. 5368 is a copy of one such translation, of Origen’s Homilies on Genesis, Exodus and Leviticus, the first three books of the Bible.

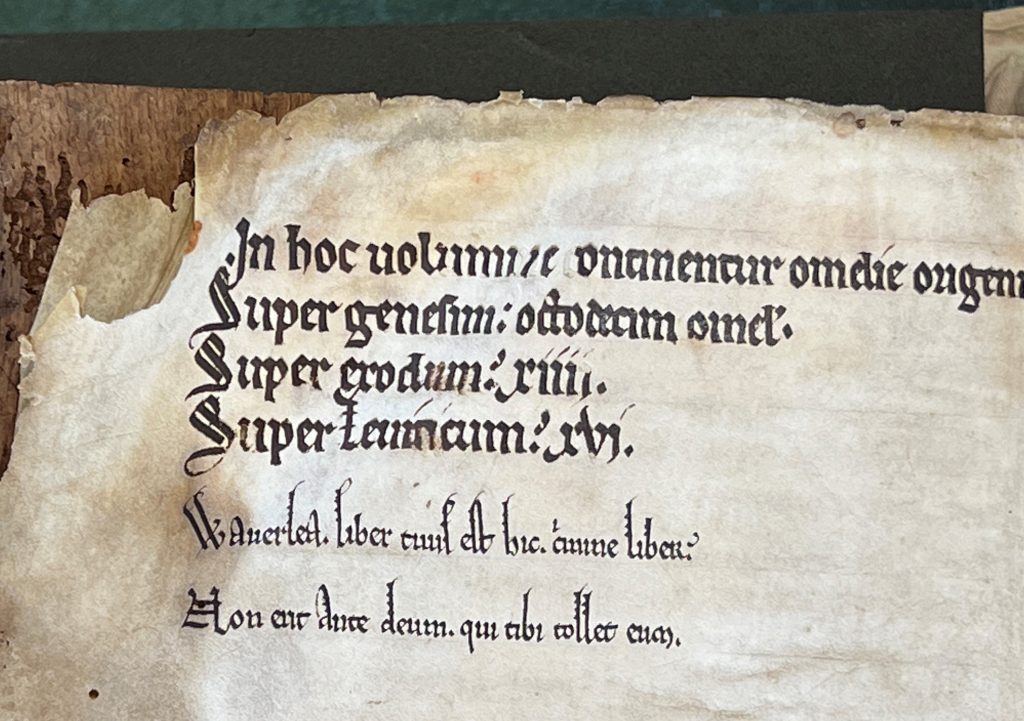

The manuscript was made for, and possibly by, the Cistercian monastic community at Waverley Abbey in Surrey. Waverley’s ownership inscription and warning to potential thieves is still present on one of the opening flyleaves: ‘Waverlea, liber tuus est hic, crimine liber | Non erit ante deum qui tibi tollet eum’ (Waverley, your book is here. Anyone who steals [it] from you will not be free from sin before God). Waverley was founded in 1128 by William Giffard, bishop of Winchester c. 1100–1129. William invited thirteen monks from the Cistercian abbey of L’Aumône in France, a daughter house of the Cistercian headquarters at Cîteaux, to fill his new foundation and to live as one abbot and twelve monks in imitation of Jesus and his twelve apostles. Despite its status as the first Cistercian foundation in England, Waverley was not a rich abbey and suffered from several natural disasters and various ecclesiastical and secular power struggles.

In 1536, Waverley was identified as an early candidate for dissolution due to its poor finances and low number of monks. Within a few months, its inhabitants were dispersed and the abbey’s land and property given to William Fitzwilliam, 1st Earl of Southampton (?1490–1542). Add. 5368 probably left Waverley when the abbey’s possessions were distributed or sold. What happened to the volume over the next few hundred years is unknown. It resurfaced in March 1913, when it was sold by the Cope family of Bramshill House in Hampshire to the bookseller P.M. Barnard, who in turn sold it in May that year to Cambridge University Library, where it has remained ever since.

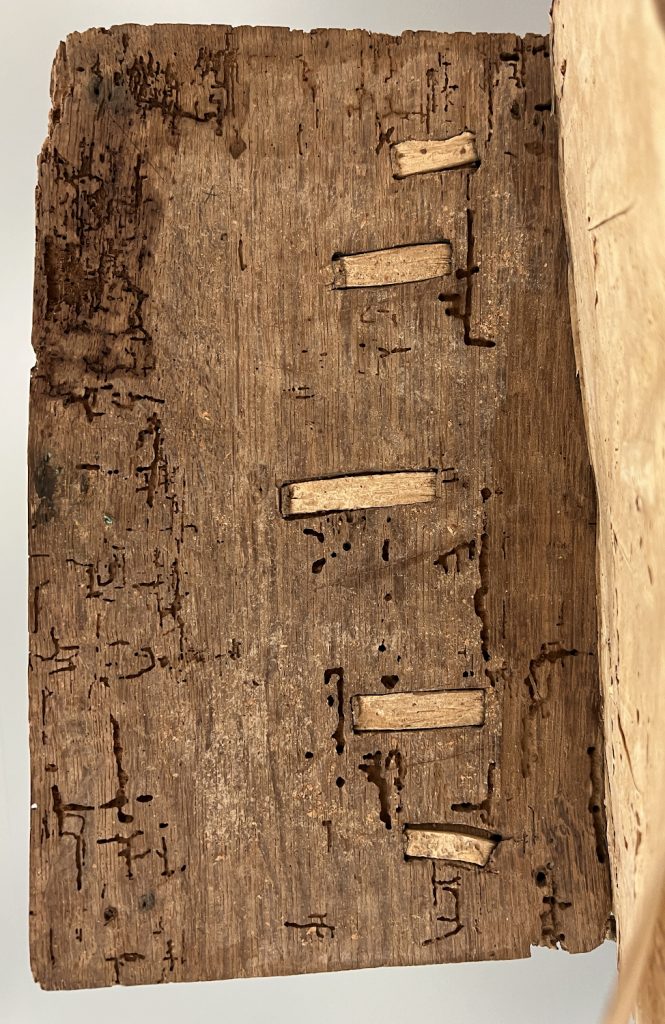

Working with Add. 5368 in its present state is not a typical cataloguing experience. The volume retains part of its medieval binding, and what remains is rather damaged. There is no cover material or leather, no right (back) board, the final few leaves of parchment have been lost, and the front (left) board is not particularly stable. However, the volume does present an excellent chance to study a medieval binding at close-hand and to examine features of the medieval sewing and construction that are usually hidden by covers and pastedowns in more complete examples.

Indeed, close inspection of this beautiful and delicate volume revealed something remarkable. Above the ownership inscription is a brief summary of the contents of the volume written in a rich dark ink. Owing to the way in which the manuscript has degraded over the centuries, the surface of the page has become unstable and some of the letters are beginning to lift from the page.

Typically, pigments become friable and crumble into powder as they break down in response to damage or improper storage conditions. Here, however, the ink is instead peeling away from the surface of the leaf in complete penstrokes or even whole letters. Some damage is to be expected in books that have lasted for hundreds of years, often surviving fires, floods, damp, political and ecclesiastical upheaval, and handling by countless readers in the process. Fortunately, Cambridge University Library’s expert, in-house Conservation & Collection Care department can repair some of this wear-and-tear, stabilise books prior to photography, and ensure that the manuscripts may safely be studied and displayed for centuries to come. Such treatment is an integral part of digitisation and cataloguing projects led by Cambridge University Library, including Curious Cures.

As soon as the peeling letters were spotted, I notified the Conservation team and Add. 5368 was taken into their expert care. The cause — and an appropriate treatment — can only be determined through a full assessment of the volume, which will be the conservators’ first task. They explained that such lifting usually occurs as a result of the use of a relatively thick ink on parchment that has subsequently become wet or been exposed to humid conditions for a long period. Parchment is hydroscopic: it absorbs and releases moisture depending on its environment. As it dries, it contracts, and this can cause the ink to lift from the surface of the page. Indeed, Add. 5368 contains several patches of water and humidity damage that were sustained before the manuscript was purchased by the Library in 1913. This may have set the peeling process in motion. A typical response may be to put the manuscript under a microscope and apply fish glue or isinglass to the backs of the lifting letters, with a very fine one- or two-hair brush, in order to secure them once more to the page.

The treatment of this manuscript will be documented by the Curious Cures Project Conservators, Marina Kruger-Pelissari and Rachel Sawicki, with photography by the Digital Content Unit, and will feature in a forthcoming blog post – so stay tuned to see one of the Curious Cures manuscripts receive a curious cure of its own!

Sarah Gilbert, Project Cataloguer, Curious Cures in Cambridge Libraries

This is truly amazing. Glueing them back? What an amazing work. I try to imaging how this works out on party’s? ‘What do you do for a job?’ ‘I glue letters back in a book.’

And the binding is beautiful. Not often you see a romanesque (or karolingian?) Binding so well preserved without covering. Those endbands (i’ve lost the English words for this type…). And the laced thru sewing supports.

Just an amazing book. Love to read more in the future.

Thank you Astrid. We’re glad you enjoyed it.

A 1 or 2 hair brush! Makes me think of the micro miniature sculpturist Willard Wigan.