Pricking and Pouncing: Alchemical Discoveries in Special Collections

By Anke Timmermann, Munby Fellow in Bibliography 2013-14

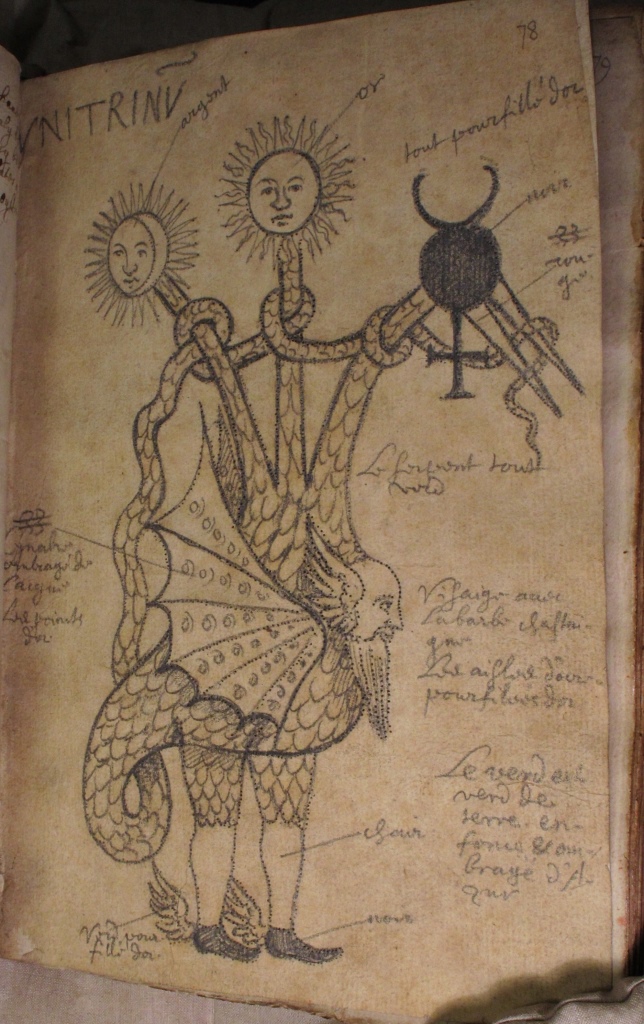

Dragon, man and god combined: a winged messenger of alchemy past. My recent encounter with this personification of alchemical principles in a seventeenth-century manuscript (CUL MS Gg.1.8) was certainly unexpected. Described as a ‘small quarto, on paper, written in the XVIIth century’ containing three works on alchemy, the volume seemed innocuous enough. I was forewarned that I should find ‘allegorical illustrations’, among them this ‘adaptation of an ophite [intended to mean gnostic or esoteric] emblem’.[1] But like many deceptively unassuming manuscripts in Cambridge collections, this volume proved much more intriguing.

Who is this draconic gentleman? As ‘Spiritus Mercurialis’ he would be familiar to some readers of the works of C.G. Jung, where he is reproduced from an unidentified German manuscript of 1600, a rather colourful, red-booted and black-faced version of the Cantabrigian pencil sketch. The image is used on the cover of this recent edition of Jung’s Aspects of the Masculine. To the more versed reader of early modern printed books, however, he is recognisable as an illustration from Giovanni Battista Nazari, Il metamorfosi metallico et humano (Brescia, 1564), f. 28v.[2]

The affinity between Nazari’s work and the mystical-erotic-literary Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (full text available from Project Gutenberg) has been remarked upon variously in literature.[3] This dragon/man also reminds of fabulous illustrations of the apocalypse, military technology, dream visions or unusual books of hours of the Renaissance.[4]

The question of what brought our alchemical messenger creature to Cambridge is intriguing, even beyond the fact that the volume, as part of the two-letter classmarked collections, has a modern binding that does not represent an original collation of its contents. Unfortunately, the origins of this leaf in CUL MS Gg.1.8 are lost, or at least not obvious. But something both noticeable and notable reveals itself upon turning over the leaf: the figure’s outline is pricked, evenly, to create a ghost image on the reverse. When the page is held up against a light the figure appears, ‘illuminated’. The purpose of this pricking is clear: in order to produce an accurate, proportionate copy of this image all one would need to do is to encourage ink or a coloured powder to transfer through these prick holes onto a surface underneath. This method, known as pouncing, has been recently described in detail in the Folger Library’s blog. In a way, then, our allegorical figure travels in the spirit of reproduction. The French annotations surrounding this holy image detail the colours to be applied to finish the copy. An early modern version of joining the dots and drawing by numbers, if you will.

How many copies were actually produced (the page is clean but forcefully drawn, perhaps to avoid abrasion during pouncing?), how accurately the colour instructions were followed, and how they made their way through France, England or indeed Germany into manuscripts that would be perused by Carl Gustav Jung is a story that awaits discovery.

[1] Catalogue of the Manuscripts preserved in the Library of the University of Cambridge by Henry Richards Luard vol. 3 (1858), entry 1403.

[2] This identification would have been much more time-consuming without the help of the Alchemy Website.

[3] See e.g. Didier Kahn, Alchimie et Paracelsisme en France à la fin de la Renaissance (1567-1625) (Geneva, 2007), 128; also pp. 207 and 664 on Nazari’s work and editions.

Hi Anke,

Some random comments:

“an ophite [intended to mean gnostic or esoteric] emblem…”

“The Ophites or Ophians (Greek ophianoi ὄφιανοι, from Greek ophis ὄφις “snake”) were members of a Christian Gnostic sect depicted by Hippolytus of Rome (170–235) in a lost work, the Syntagma.”

Quite a good Wiki article on them:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ophites

See also:

http://rhr.revues.org/5351

Whether the modern practice of serpent-handling is connected with his sect in any way I’m not sure:

http://natzrim.blogspot.com/2012/05/west-virginian-pastor-dies-snake.html

Nazari is a curious name and doesn’t sound especially Italian. A family of Nazarenes perhaps?

http://www.sacred-texts.com/the/iu/iu106.htm

Nice blog :o)

Paul

This is so interesting – I have seen ponced drawings on separate sheets, never in a bound book, Fascinating image.

Pingback: First Monday Library Chat: Cambridge University Library | The Recipes Project