New acquisitions from Edward Gibbon’s library

On this day in 1737 was born Edward Gibbon: historian, Member of Parliament and author of The history of the decline & fall of the Roman Empire (London, 1776-1788). The University Library holds a number of books from his personal library, and has recently acquired two more, which are discussed in this post.

Brought up in Putney and schooled at Kingston-upon-Thames and Westminster, Gibbon was later sent to Oxford, matriculating at Magdalen College in 1752 where, he later wrote in his autobiography, “My vanity was flattered by the velvet cap and silk gown which distinguish a gentleman commoner from a plebeian student.” Just fourteen “idle and unprofitable” months were spent at Oxford before his father removed him as a result of Gibbon’s conversion to Catholicism. He was sent to Lausanne to be tutored, and did not enjoy the early days of his new life: “From a man I was again degraded to the dependence of a schoolboy…I received a small monthly allowance for my pocket-money…[and] no longer enjoyed the indispensable comfort of a servant. My condition seemed as destitute of hope as it was devoid of pleasure.” However, five productive years were spent in Switzerland and it was a place to which he would later return. From 1758 until 1772 much time was spent at Buriton, his father’s country mansion in Hampshire, and it was there that he wrote his first major work, Essai sur l’étude de la littérature (London, 1761), later published in English (in 1764). A presentation copy of the French edition is among the books of Geoffrey Keynes (the spine is illustrated below left), now part of the Library’s collections. He returned to Lausanne in 1763 and in the following year visited Florence and Rome where, on 15 October 1764, the idea of writing his great work on the history of the decline and fall of the city came to him: “As I sat musing amidst the ruins of the Capitol, while the bare-footed friars were singing Vespers in the Temple of Jupiter, the idea of writing the decline and fall of the city first started to my mind.” The writing of such a work required many books and Gibbon built up an impressive personal library of classical, religious and historical writers. Gibbon noted in his autobiography that “I have gradually formed a numerous and select library, the foundation of my works, and the best comfort of my life, both at home and abroad.”

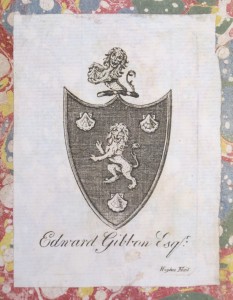

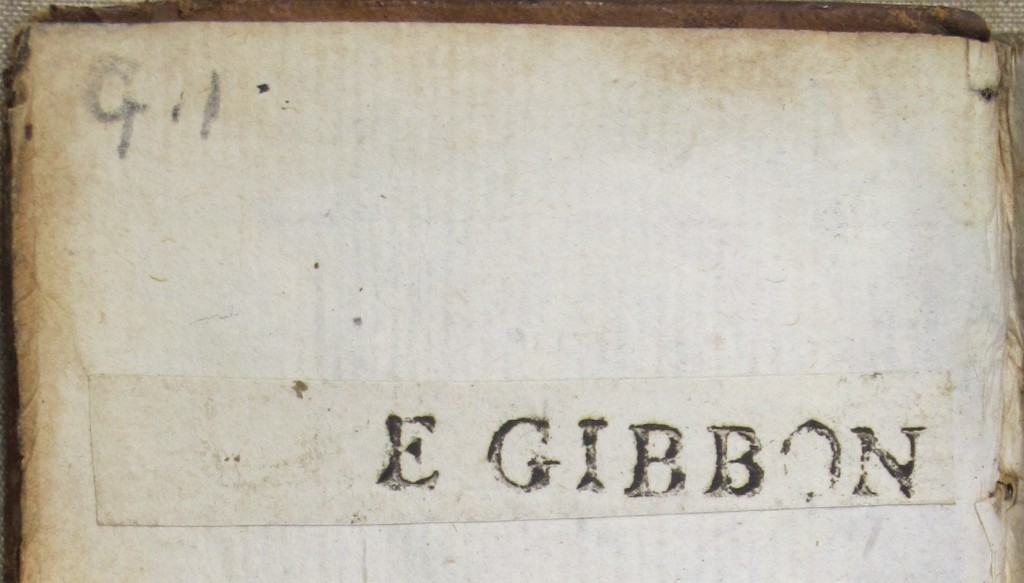

His father died in 1770 and by 1772 Gibbon had left Buriton and taken up residence at Bentinck Street in London, a few minutes’ walk north of Oxford Street. A catalogue of Gibbon’s library here was made in 1777, listing about 2000 titles in 3300 volumes. Books continued to be added throughout the 1770s and 1780s, when Gibbon served as an MP (for Liskeard 1774-1780 and Lymington 1781-1784). But in 1783, Gibbon left London for Lausanne and took just 2000 volumes with him, leaving the remainder at his friend Lord Sheffield’s house in Downing Street. While he worked hard on the final two volumes of his Decline and fall books poured into the house, with £3000 being spent on books alone between 1785 and 1788. A card catalogue was constructed – the word ‘card’ being important here – using the blank backs of 1676 playing cards, and this was kept up to date until 1789, occasionally in Gibbon’s own hand. Gibbon’s books were distinguished by the presence of a fine armorial bookplate or (though sometimes in addition to) a simple printed name-label. By now there were some 6000-7000 volumes at Lausanne, and in 1792 his friend Lord Sheffield became concerned at the ultimate fate of the library, which he feared would be spoiled at the hands of French revolutionaries or dispersed at Gibbon’s death. Sheffield proposed in a letter that the books be left to him and kept together as ‘The Gibbonian Collection’ at his country seat, Sheffield Place in Sussex. Gibbon thought this a ridiculous idea, and much preferred the idea that his books would be dispersed at his death: “I consider a public sale as the most laudable method of disposing of it…If indeed a true liberal public library existed in London, I might be tempted to enrich the catalogue and encourage the institution: but to bury my treasure in a country mansion under the key of a jealous master! I am not flattered by the Gibbonian collection, and shall own my presumptuous belief that six quarto volumes [his Decline and fall] may be sufficient for the preservation of that name.” The following year, 1793, Sheffield’s wife died and Gibbon travelled to London to console his friend, never to see his beloved books again: Gibbon himself became ill, and died on 16 January 1794. Although Gibbon had no great connection with Cambridge, it has come to be that a significant portion of his once great library is now to be found in the libraries of this university. The story of the dispersal and how the books came to be in Cambridge is one with many twists and turns.

In 1783 upon moving to Lausanne Gibbon’s library was split in two, 2000 volumes going with him to form the nucleus of his new collection and the rest (presumably at least 1300 volumes if we know he had 3300 volumes in 1777) remaining in London with Lord Sheffield. At Gibbon’s death in 1794, Sheffield – Gibbon’s executor – sold the Lausanne library to William Beckford (eccentric author of Vathek and collector of immense financial means), who lived at Fonthill Abbey in Wiltshire but “liked to have deposits of books in different parts of Europe”. In Beckford’s own words: “I bought Gibbon’s library to have something to read when I passed through Lausanne. I shut myself up for six weeks from early in the morning until night, only now and then taking a ride. The people thought me mad. I read myself nearly blind”. Beckford later gave the Lausanne library to his physician Dr Frederic Schöll, who sold part of it to one John Walter Halliday, keeping the remainder until 1832, when it was offered for sale in Lausanne. The Halliday portion was later presented by his widow to the Rev. Charles Bedot in 1873, and passed to Bedot’s son, who died in 1927. Most of it was sold to a dealer in 1928 who attempted to sell the collection en bloc, potentially to Magdalen College Oxford, who rejected the rather steep asking price of over £4000. The dispersal of Gibbon’s library finally came (more or less) to an end in 1934 when this portion (1412 volumes) was sold at Sotheby’s in London for a little over £1575. Cambridge is lucky that the collections of two significant buyers at the 1934 sale would later find their way into Cambridge libraries: Victor, third Baron Rothschild (1910-1990), and Geoffrey Keynes (1887-1982). The Rothschild collection of Gibbon’s books, amounting to some 75 titles, is a very small part of the immense and very fine collection of around 3000 eighteenth-century English books – many of them in fine bindings – amassed by Lord Rothschild between 1932 (when he was an undergraduate at Trinity) and 1951 (when he gave much of the collection to his college, the rest following in 1969). The collection fills an entire bay of the Wren Library and chief among those books from Gibbon’s library is his large folio copy of Herodotus (Amsterdam, 1763), which contains some 3300 words of notes in Gibbon’s own hand (now RW.50.15). The interesting tale of its route into Rothschild’s hands is recorded by Geoffrey Keynes in his own autobiography (The gates of memory, 1981). Keynes came across the volume when examining books at Sotheby’s before the sale, and noticed that the copious annotations in Gibbon’s hand had not been mentioned in the sale catalogue. He put in a bid of £10 and, after a short battle with a London bookseller – who was unaware of the folio’s significance – acquired the book for £26. He was later offered £100 for it by the London bookseller Lionel Robinson – who was acting on behalf of Lord Rothschild – but decided to keep it, eventually letting it go for £200.

Keynes’ own acquisition of books at the sale was part of his desire to publish as complete a catalogue as possible of Gibbon’s library, based on the various original catalogues and surviving books (it appeared in 1940 as ‘The library of Edward Gibbon’ and a second edition was issued in 1980). Keynes saw this project as “a worthwhile objective to assemble the foundation on which one of the greatest intellectual efforts of any human mind [the Decline & fall] had been based.” It was just one of many such projects taken on by Keynes throughout his long life, based on his collecting habits; from complete author collections assembled by his own hand, he would compile bibliographies of John Donne, William Blake, Jane Austen and Rupert Brooke (whom he knew), to name but a few. Keynes eventually owned about 25 books from Gibbon’s library, most acquired at the 1934 sale but others picked up in later years. The majority of these (for he gave away at least one of Gibbon’s books to an institutional library) came to the University Library with his collection of about 8000 volumes after his death – aged 95 – in 1982. Books from Gibbon’s library remain desirable to many collectors and often come up for sale: at least five titles are currently on offer with booksellers in the UK and USA and even David’s bookshop here in Cambridge have sold two or three volumes in the last few years. Coincidentally, our two recent acquisitions came from the library of a friend of Keynes – Cosmo Gordon (1886-1965) – whose books have been offered for sale by the London bookseller Bernard Quaritch in two catalogues (one in 2010 and the most recent in March this year). Gordon was an undergraduate at Cambridge, along with Keynes, in the early years of the twentieth century, and Keynes spoke warmly of his debt to his friend in his autobiography: “Cosmo and I found our tastes and interests were always in harmony and I came to love his particular sense of humour and gentle goodness, as well as to respect his unusual style of scholarship and general culture.” The recent catalogue of Gordon’s books contained five books from Gibbon’s library, of which two are now in the University Library.

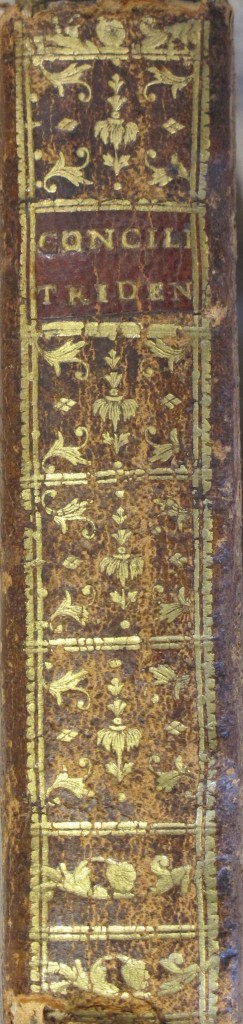

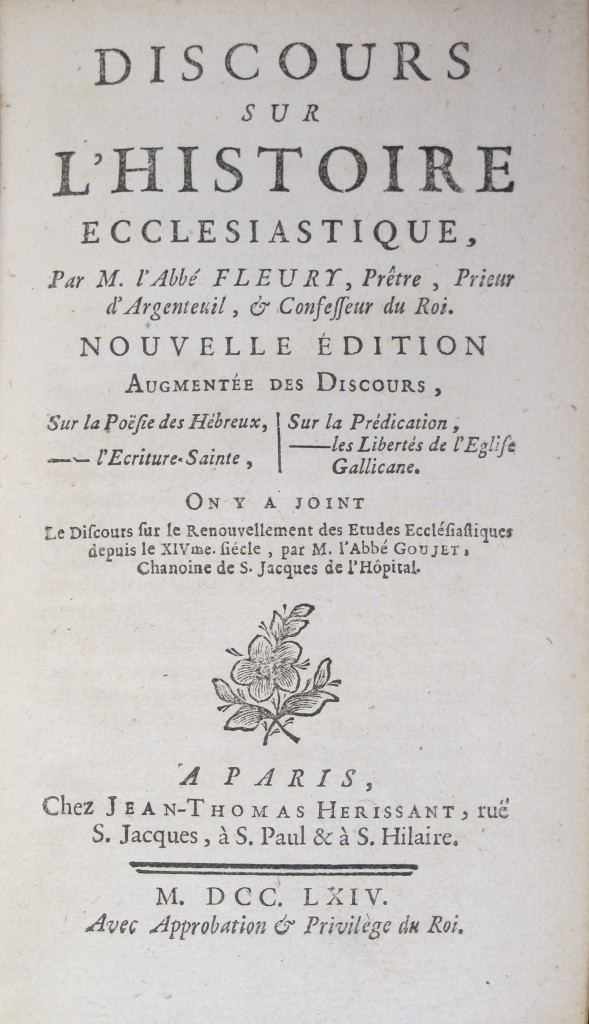

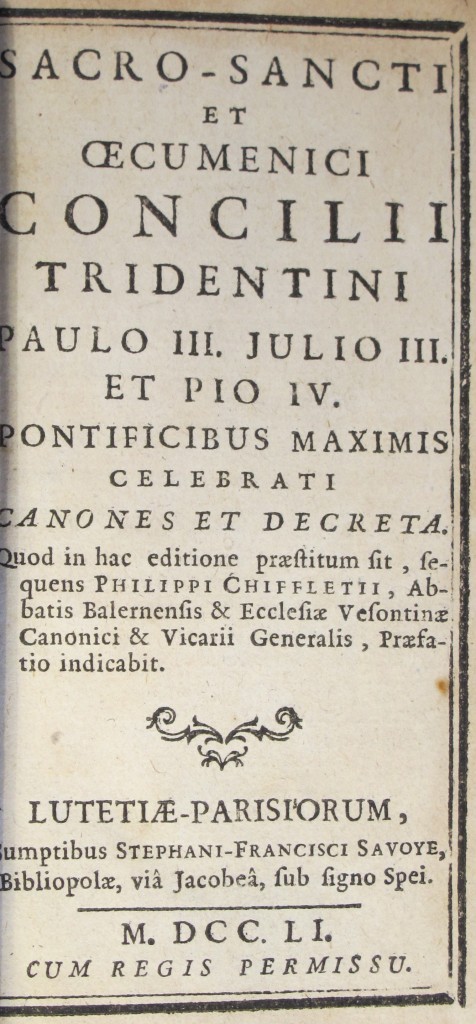

Both were printed in Paris in the mid-eighteenth century and concern ecclesiastical history. The first, Claude Fleury’s Discours sur l’histoire ecclesiastique (Paris, 1764), was one of those volumes Gibbon took with him from London to Lausanne in 1783. It contains his fine bookplate and was among the portion of books sold to Beckford, and which passed to Scholl, then Halliday, before being sold at Sotheby’s in 1934 (lot 74). Only one other copy of this edition is recorded in the UK, at Lambeth Palace. The second, Sacro-sancti et œcumenici Concilii Tridentini (Paris, 1751) – a work on the mid-sixteenth-century Council of Trent – contains Gibbon’s more primitive name-label and took the same route to Sotheby’s in 1934 (lot 146). Again, only one other copy of this edition is known in the UK, at Aberdeen University.

These two new additions, along with the two-dozen books from Keynes’ library, a few books scattered among other collections in the Library – including one of Gibbon’s own copies of the first volume of the first edition of his Decline & fall (S520.b.77.1) and a three-volume folio edition of Eusebius’ Ecclesiasticae historiae in Greek & Latin (Cambridge, 1720: Cam.a.720.1-3) with his bookplate – and the Rothschild Collection at Trinity, make Cambridge an important centre for the study of Gibbon’s literary work and, almost three centuries after his birth, we are certain that our new acquisitions will be of interest to those studying Gibbon’s life and work.

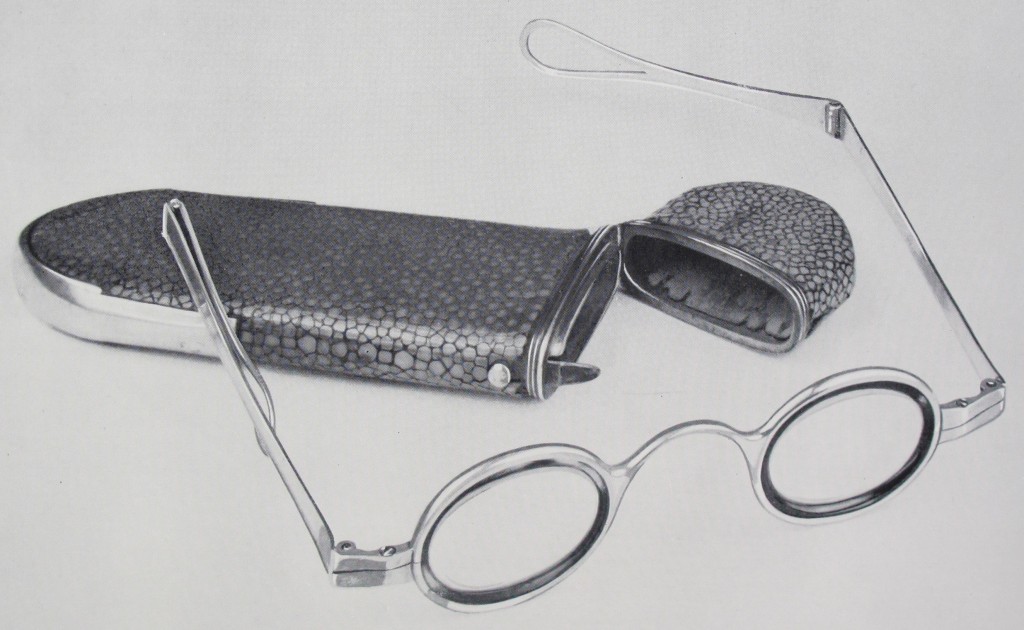

Edward Gibbon’s spectacles, c. 1770. Sold in the Sotheby’s sale on 20 December 1934, they were bought by Lord Rothschild, who in 1961 gave them to Tim Munby (Librarian of King’s College). They were sold in his sale (Sotheby’s, 5 April 1976, lot 669) along with one of Gibbon’s own copies of the Decline and fall, and both remain in private hands. Illustration from J. H. Doggart, “Gibbon’s eyesight”, pp. 406-11 in Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society vol. III, part V (1963).

Further reading:

Edward Gibbon: Autobiography (London, 1907)

Geoffrey Keynes: The library of Edward Gibbon (London, 1940), esp. the introduction (pp. 11-36). Second edition Godalming, 1980.

Geoffrey Keynes: The gates of memory (Oxford, 1981), pp. 246-251

[Rothschild]: The Rothschild Library: a catalogue… (Cambridge, 1954), vol. 1, pp. 235-246

[Sotheby’s]: Catalogue of the library of Edward Gibbon (London: sold 20 December 1934)

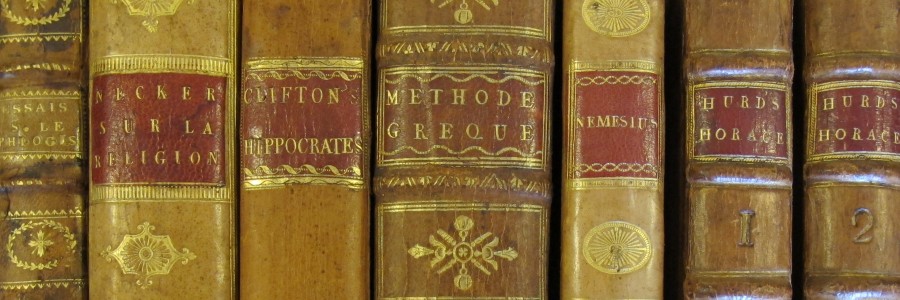

The book spines pictured at the head of this post are all eighteenth-century bindings from Gibbon’s library now in the Keynes Collection, from L to R: Keynes.R.3.20, R.3.22, R.3.21, R.3.28, R.4.16 & R.3.15-16

Hello. I would love to get a list of all of Gibbon’s books used in writing the decline and fall. Do you have such a catalogue available? Thanks, Vincent

Thanks you for your comment Vincent. The thing to find is the second edition (1980) of Geoffrey Keynes’s ‘The library of Edward Gibbon: a catalogue edited and introduced by Geoffrey Keynes’, which can be found quite cheaply for sale online. It lists all the books known to have belonged to Gibbon, thanks to several surviving manuscript catalogues and Gibbon’s own card catalogue, and talks about the sources he’d have used for his History. Liam Sims (Rare Books Specialist).