Cantabrigia Geographia: Cambridge in Maps 1574-1798

In the Map Room at Cambridge University Library it is possible to travel the world through both time and space from the comfort of a single desk. From early giant Burmese fabric maps, cattle trails across America and linguistic patterns across Europe to the new buildings and infrastructure that can be seen in minutiae in the Ordnance Survey’s digital map data, an infinite number of details about the world we live in can be revealed.

Every journey has to start somewhere, and for the latest exhibition in the Entrance Hall display cases at the University Library we decided to stay at home and look at Cambridge through some of the earliest maps of the city to see the changes that occurred from the Tudor period to the end of the eighteenth century.

During this time Cambridge alumni included Francis Bacon, Isaac Newton, John Milton, Samuel Pepys and William Wordsworth to name a few. The maps on display give us a chance to see how the streets and buildings they would have walked past and used daily appeared to them (although as with every map some leeway has to be given for the artistic licence taken by the cartographers who produced them).

It was a year after Francis Bacon entered Trinity College for the first time that the earliest complete map of the town, dating from 1574, was produced. Drawn and engraved by Richard Lyne, a painter, engraver and cartographer who had been employed by Archbishop Matthew Parker (the Master of Corpus Christi College from 1544 to 1553), the map presents a bird’s-eye view of the city revealing features that include the tightly enclosed core of the town centre, the economic and social centre around the Market Place (which was considerably larger than today) and that Garret Hostel Green was an island.

The map was often included in copies of John Caius’ work De antiquitate Cantebrigiensis Academiæ, in which he was attempting to argue that Cambridge University was older than Oxford, although it is likely that it was Parker who paid for its creation.

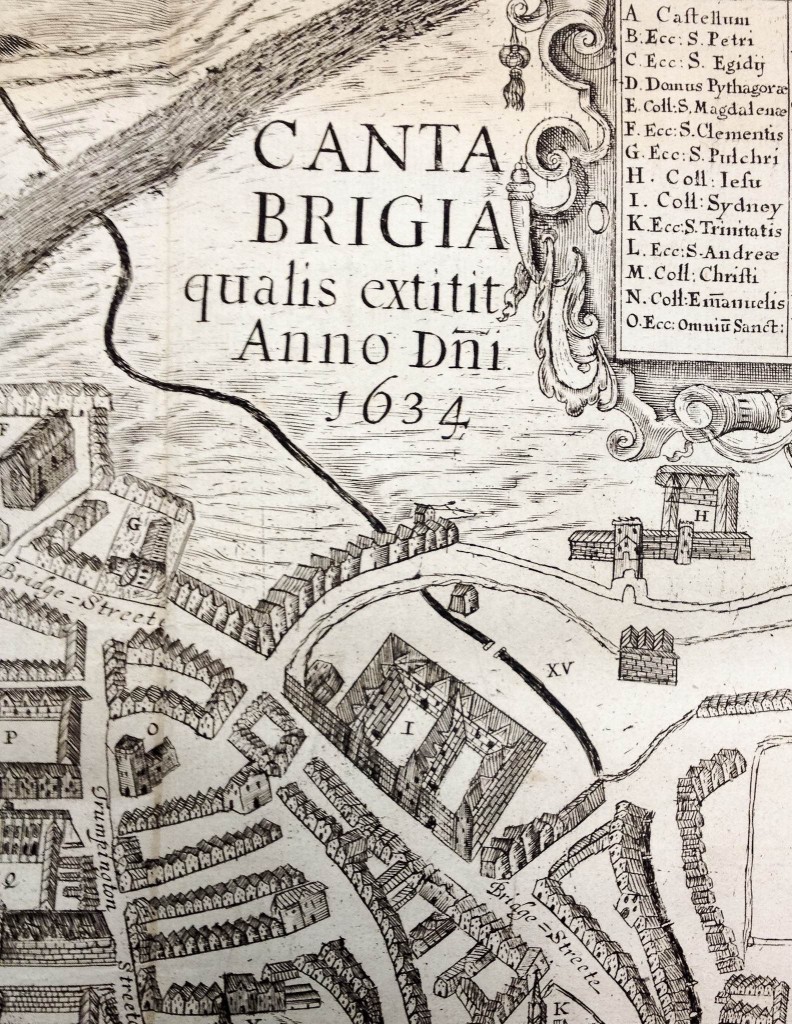

Extract from the 1634 map of Cambridge showing Sidney Sussex college

The second map of Cambridge was published just a year later in the second second book of the six volume folio Civitates Orbis Terrarum, published from 1572-1617 by George Braun and the engraver Frans Hogenberg.

The map depicts Cambridge from the west – a different orientation to Lyne’s map. However, closer inspection reveals strong resemblances between the two – both give prominence to college buildings over the non-collegiate structures within the town. It is likely that both were drawn by the same draftsman or alternatively that this map was carefully copied from Lyne’s so as to appear to be a new map without including any new information.

The Bird’s-eye style means that these early plans have little reference to the accurate proportions and relative positions that we would expect from a modern map. They do, however, present a picture of the architecture of the town and give a sense of scale to the size of the buildings that a map in a more modern scientific style cannot reproduce.

The final map of this type to be shown is that produced in 1634 and often used to accompany Thomas Fuller’s History of the University of Cambridge since the Conquest (1655). Although presenting a largely inaccurate view of Cambridge’s buildings, representations of Sidney Sussex College (founded in 1594) and the stone bridge built at King’s College in 1627 are shown on a map of the city for the first time.

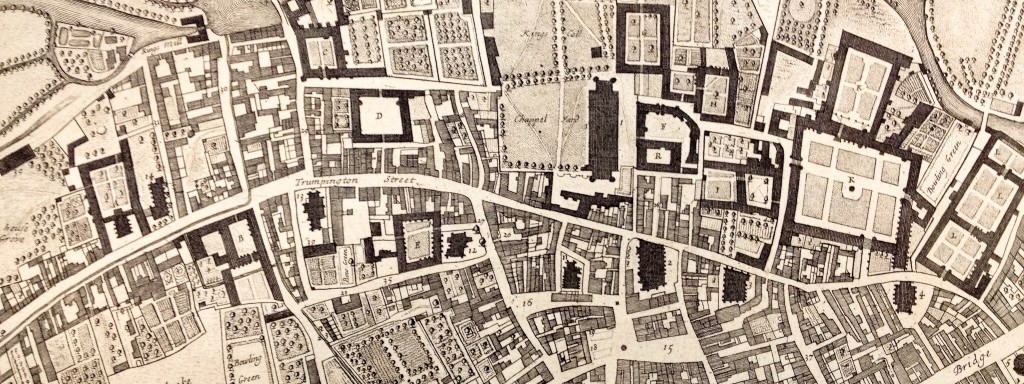

The centre of Cambridge from Loggan’s map of 1688

The first map of Cambridge to present the city as if seen vertically from above in a style that resembles the standards and accuracy we would expect in a modern map was published in 1688 by David Loggan.

The Market and Petty Cury area of Cambridge from Custance’s map, 1798

Included in his Cantabrigia Illustrata (published in 1690 alongside many illustrations of the town and colleges compiled over a ten-year period before his appointment to the role of official engraver to the University) Loggan’s plan shows a much greater density of construction within the town that had been built to cope with the larger population levels and increased commercial activity, as well as the remodelling and new building that had occurred at Trinity, St Catharine’s, Gonville and Caius, St John’s, Emmanuel and Christ’s Colleges.

The final map in this display was produced by William Custance in 1798. Custance was a builder, land agent, surveyor and enclosure commissioner who by 1801 was living in Chesterton and was employed by many Cambridge colleges to compile maps and provide surveys and valuations of them.

His map gives a very clear picture of Cambridge just before the major changes that were to take place in the early part of the nineteenth century. It is notable that although the outline of the city had changed little from the earliest maps of the town, further intensification of building can be seen, especially in the centre of the town where virtually all open land has now been built on.

The exhibition will remain on view in the Library’s Entrance Hall cases until Saturday 26 September and all are welcome to visit (Monday-Friday 9.00-19.00, Saturday 9.00-17.00). Please contact the Map Department (maps@lib.cam.ac.uk) for further information