From Andalusia to Cambridge

This year the University Library celebrates the three hundredth anniversary of the acquisition of the Royal Library; this gift from King George I brought to the Library the largest and most valuable single collection ever to be acquired. Collected over many years by the scholar John Moore, it contained over 30,000 volumes, including almost 1800 manuscripts. In fact Moore’s library had the reputation for being the best collection in private hands at the time.

The Royal Library contained some of the Library’s manuscript treasures and notable early English printed books, some from Caxton’s Press. Less well known is that among the Royal Library manuscripts there were over sixty Islamic texts in Arabic, Persian or Turkish. How these came to be in John Moore’s possession is not altogether clear, but some at least, could have been from the collection of the French scholar of Arabic Isaac Casaubon (1559–1614) whose library was inherited by his son Meric and, after his father’s death, sold on to other collectors.

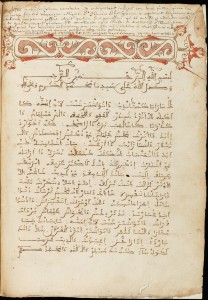

The Islamic manuscripts are wide in scope including religious texts but also examples of poetry and history. Especially interesting and unusual is the copy of ‘El breve compendio de nuestra santa ley alçunna’ (MS Dd.9.49). A contemporary catalogue of Moore’s library described it as ‘the Book concerning the Rites of the Mahometan Religion written by a Moor in African Letters but Spanish Language’. This text is indeed a compendium of Islamic law written by Baray de Reminjo with the help of a young scholar known as Mancebo de Arévalo. The treatise was composed in Spain in the third decade of the 16th century and is written in Aljamiado.

Aljamiado is a term used to describe texts transcribed from European languages, in this case Spanish, into Arabic script. It was used in Spain as an everyday language by the Muslim population there, Arabic itself being reserved for more academic or religious texts. This form of Spanish written in Arabic script seems to have originated in the 15th century but was most commonly in use in the 16th and it played an important role in preserving the traditions of the Moriscos in Spain. They were the Islamic communities of Spain who were forced to convert to Christianity or face expulsion. Some of the Moriscos, however, kept their original beliefs in secret, in part, through the use of texts in Aljamiado.

Another interesting feature of this particular manuscript is that details of its former ownership are written in a Latin note at the head of the first leaf of text. This throws some light on its long journey from Spain to England. The Latin text describes the manuscript’s donation from Engelbertus van Engelen (1660-1723), a Dutch scholar based in Utrecht. In April 1703 he gave the manuscript to the Hebrew scholar Henry Sike (1669-1712) also active in Utrecht in the same era. Sike was a German oriental scholar of some note, born in Bremen, but who also worked in various Dutch university cities and became prominent in the movement to study New Testament apocrypha. Sike became known through mutual friends in Utrecht to Richard Bentley, the Master of Trinity College, Cambridge, who facilitated his appointment as Regius Professor of Hebrew in Cambridge in 1704. As well as being a friend of Bentley he had other colleagues at Trinity, including Newton. But he also had his detractors and critics and he eventually committed suicide in his rooms in Nevile’s Court in Trinity in 1712.

Sometime after Sike’s death, the manuscript was bought by Moore in a parcel of other manuscripts from his estate, and hence it entered the Royal Library collection. The details of how the manuscript travelled from Spain to the Netherlands in the first place remain unclear, but the Dutch cities where Arabic studies flourished at that time were in close proximity to the Spanish Netherlands. Also, the expulsion of the Moriscos from Spain resulted in the dispersal of the Muslim population into other countries in Europe and such refugees would very likely have taken some of their books along with them.

Images of the whole manuscript can be found in the Digital Library.