His Royal Favour: the Books that Built the Library

The University Library’s latest exhibition looks in detail at the formation and arrival in Cambridge of the Royal Library, a collection that has been at the heart of University research for three hundred years.

First Bishop of Norwich and then Bishop of Ely, John Moore was a voracious collector of books and manuscripts, amassing some 30,000 volumes in his library in Ely Palace in London. Numerous scholars note in their diaries and forewords his generosity to all who wished to use his collection. It was a private library, but in effect also a public resource. When he died, it was fitting that it should have been gifted to a University rather than dispersed or retained in private hands.

This single collection is, along with the early manuscripts and what we now call the Stars (the books held in the medieval library before 1715), the great historic core of the Library. The books are important not only for their texts, but for the simple fact of their age; every item Moore collected is a historical artefact in and of itself. The Library is greatly privileged to have benefited from Moore’s diligent collecting, and the fact that so many iconic books are held within this one collection. The challenge for me as exhibition curator was in selecting just a handful of items to give an impression of the treasures it contains. Telling the story of the collection was fairly straightforward; limiting myself to only around 60 items to do that was much more difficult.

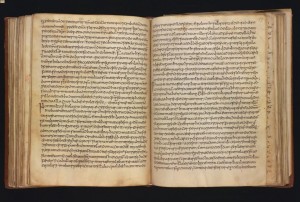

One of the earliest known manuscripts of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People (MS Kk.5.16)

As a medievalist by training, I simply had to include the eighth-century manuscript of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People (the ‘Moore Bede’), written at his own monastery within a decade or two of his death. I also couldn’t leave out the ‘Moore Psalter’, a 13th-century French manuscript with stunning illuminated decoration, in which every spare space is filled with animals and figures both real and imagined. Both of these manuscripts have been added to the Cambridge Digital Library, allowing viewers to leaf through the pages and to zoom in on the glorious decoration of the Psalter.

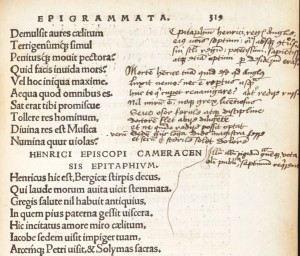

Even though these books have been in the Library for three hundred years, there is still much to discover. Within the last year, a previously unknown poem – an epitaph on King Henry VII – attributed to the philosopher and humanist Erasmus (1466-1536) was noticed in a volume of his epigrams printed in 1518. The beautiful Tudor partbook written in early sixteenth-century England is being studied closely within a project reconstructing the music of some of the most renowned early English composers by bringing together fragmentary manuscripts and digitising them. Students around the world were given the opportunity to learn more about a fifteenth-century manuscript of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales through a Massive Open Online Course run jointly by the Universities of Cambridge and Stanford.

What I hadn’t realised until I began researching this collection around two years ago in preparation for the exhibition was that the great majority of Moore’s printed books remained on open access for users to browse until the 1950s, in the elegant and simple cases on the North and South Front galleries, and indeed were still borrowable with permission. These 300-year-old cases now contain modern books; Moore’s collection is now housed in our best quality secure stacks, and fetched to readers in the Rare Books Reading Room. While most of them remain in the classes they were assigned to in the 1740s, some of the more precious have been removed to other classes including Incunabula, Rel (for fine bindings), Adversaria (for those with extensive annotations) and Syn (those which could only be borrowed with permission of the Library Syndicate). This means that many scholars are working on Moore’s books without realising; the only indication in many cases is the presence of the Royal Library bookplate.

Curating this exhibition has been a true pleasure, and a chance to delve into the lesser-known corners of one of the Library’s core collections. Curator tours are available to find out more about the items on display, and places can be booked here.