Cambridge connections: Trinity Hall and the University Library

About sixty years before the University had its own purpose-built library, William Bateman (Bishop of Norwich) founded Trinity Hall in Cambridge. It remains one of the oldest surviving colleges of the University and its Elizabethan library contains books from those early days (including two given by Bateman in 1350). Many links exist between the ancient libraries within the University – of which Trinity Hall’s is one – not least in terms of the movement of individual volumes between collections. A recent post on the Trinity Hall Old Library blog about the college’s incunabula (books printed before 1501) made me wonder if any early books now in the University Library (which celebrates its 600th anniversary in 2016) have connections to Trinity Hall. This post looks at three sixteenth-century volumes once owned by members of the college, whose contents can tell interesting stories about their long histories and connections with our university town.

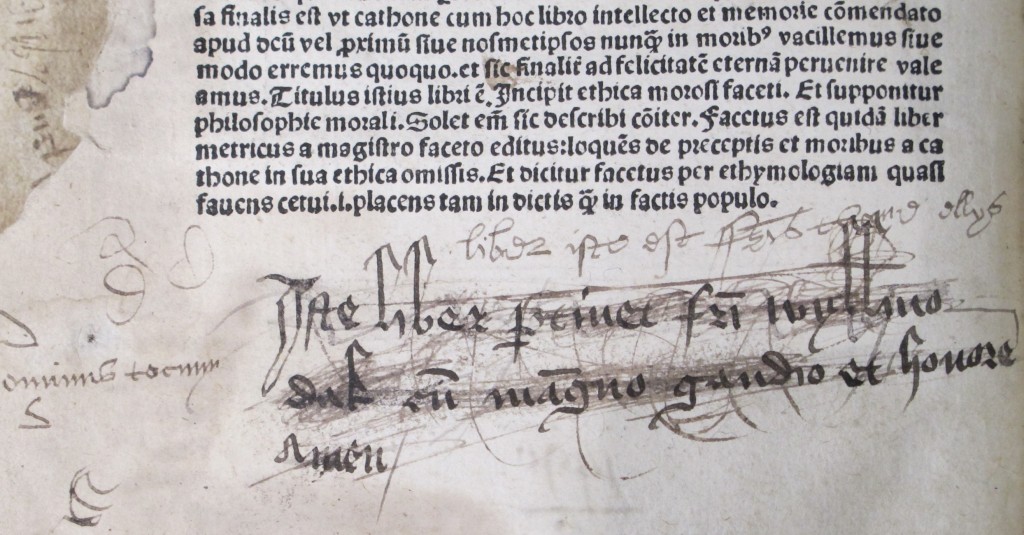

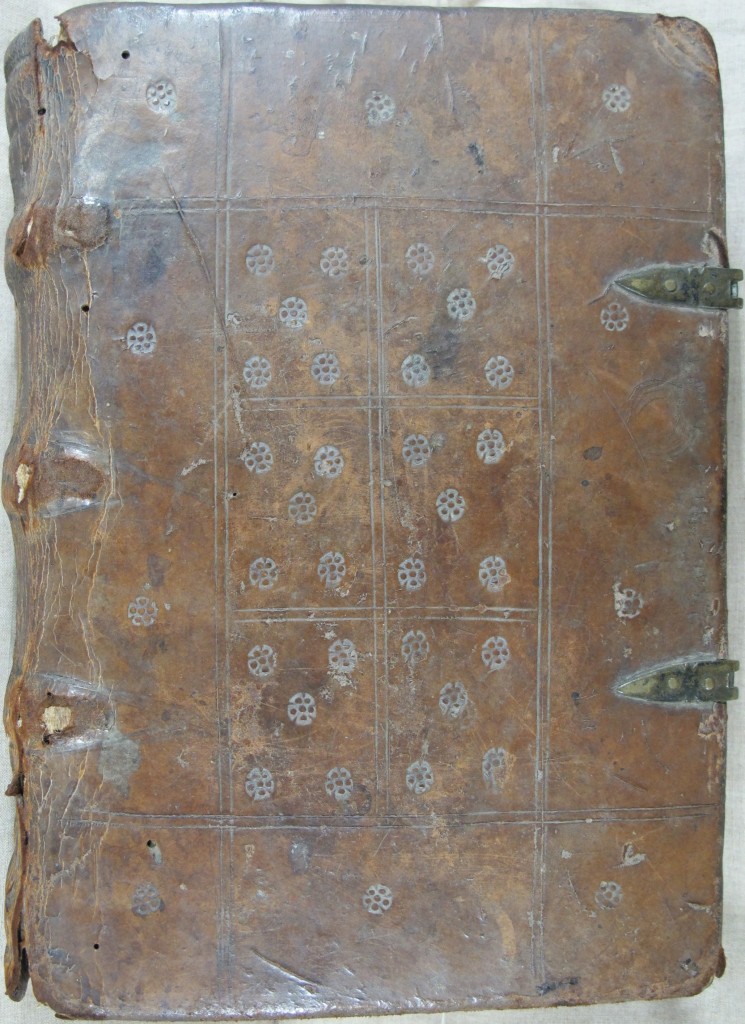

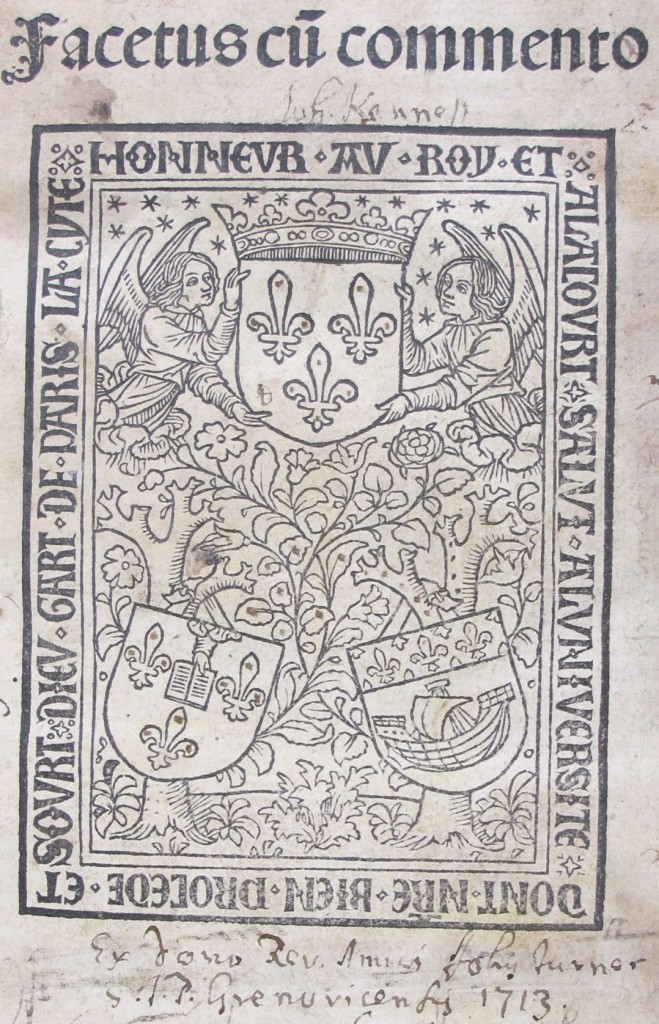

The volume with the earliest connection to Trinity Hall is a medieval blind stamped wooden binding containing five separate works, all printed in the 1490s, and all evidently in Cambridge at a very early date. Two are from the press of Richard Pynson, an important printer based in London (possibly an early assistant of England’s first printer, William Caxton), and others made their way from Cologne and Paris. The first work in the volume forms the third part (the Facetus) of an eight-part work known as the Auctores octo morales (Eight Moral Authors), a standard collection of Latin textbooks used for teaching in the medieval period, which included Aesop and the Distichs of Cato. This undated edition was printed in Paris by André Bocard, in about 1491-3, and is today exceedingly rare; the third part is recorded in just one other library – the Bodleian. One of the first owners of this copy of the Facetus was William Dakke, who is named in an inscription on the verso of the first leaf: ‘Iste liber p[er]tinet f[ratris] wyll[el]mo dak cu[m] magno gaudio et honore Amen’. Dakke is fairly well documented in Emden’s Biographical register of the University of Cambridge to 1500, which records that he had graduated (at an unknown college) as a bachelor of Canon Law by 1454/5 and that he was vicar of Meldreth church before 1475, as well as rector of Sudborne and Orford in Suffolk from 1475 onwards. His connection with Trinity Hall comes, unsurprisingly, with his expertise in the law, for he served the college as ‘Proctor at law’ in 1474, a post he held for the prior of Ely in 1469/70; surviving records tell us that he was ‘rowed from Cambridge to Ely on priory business’. Dakke died late in 1495 (his will is dated 2 September), leaving the sum of 6s 8d to the church of the Holy Sepulchre in Cambridge (the Round Church) and was buried in Orford church. During his lifetime the book passed by purchase to one Geoffrey Jullys, who bought it from Dakke and gave it to one Thomas Ellys, all of which we know thanks to another helpful inscription (on the recto of the second leaf): ‘emptus a fratre Will[el]mo Dalke [sic] per m[agist]r[um] galfridym Iullys et datus per e[un]d[em] m[agist]r[o] fr[atri] thome ellys filio suo spirituali’.

Since most of the other works in the volume are dated to 1496 or later (i.e. after Dakke’s death), we know that they can only have been bound together later on, perhaps by Ellys, whose name appears in other items in the volume. In 1713 the volume was given by one John Turner to White Kennett, then Dean of Peterborough (and from 1718, Bishop of Peterborough), whose books formed the core of the Cathedral Library. After more than 250 years in Peterborough the volume returned to Cambridge in 1970, on permanent loan with the rest of the Cathedral Library (about 7000 books). One of the most significant collections of early English books in the UL, the Peterborough library is rich in early bindings and marks of ownership.

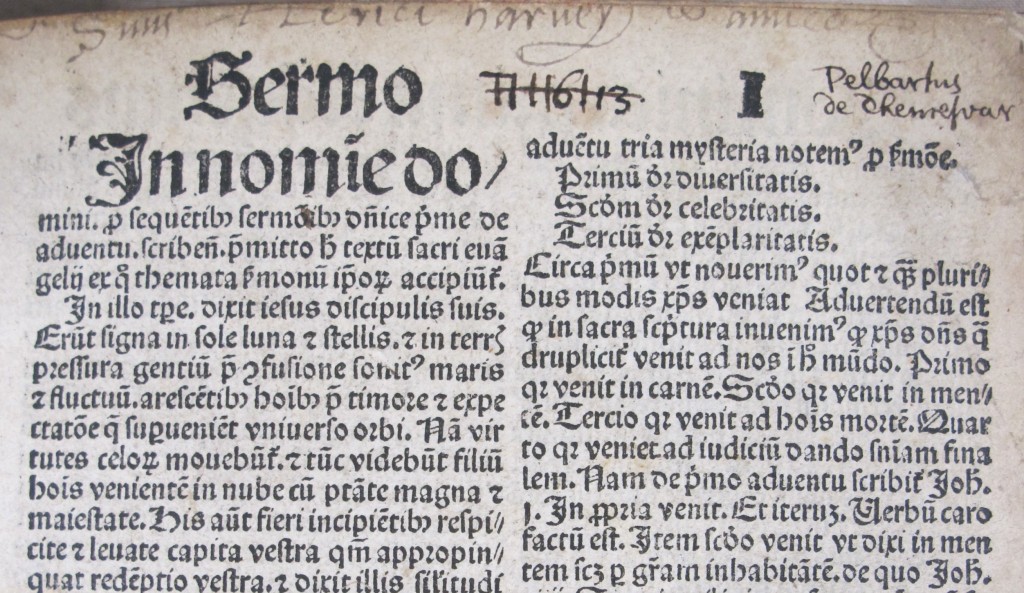

William Dakke’s connection to Trinity Hall was a fairly tenuous one, but another volume now in the UL links us with the most important individual in the college: the Master. It is an edition of sermons by the Franciscan theologian Pelbartus Ladislaus de Temesvár (1430-1503), born in Hungary, and was printed in the town of Haguenau in 1498 (then German, but now part of France). The earliest owner of the UL’s copy was one Henry Harvey (d. 1585), Master of Trinity Hall, who – in humanist style echoing the great collector Jean Grolier – inscribed the second leaf ‘Sum He[n]rici Haruey et amicor[um]’ (i.e. it belonged to ‘Henry Harvey and his friends’). Again, Harvey’s career within the University is well documented: he took his bachelor of laws degree from Trinity Hall in 1538, his doctor of laws degree in 1542 and – after serving variously as Archdeacon of Middlesex (1551-4), Vicar-general of London and Precentor of St Paul’s Cathedral (1554) – he became Master of the college in 1559, succeeding William Mowse, who was mentioned in the previous blog post. His career continued to flourish: he became Vice-Chancellor of the University in 1560 (in the same year, he gave three books to the King Edward VI School at Bury St Edmund’s) and held prebendaries of Salisbury Cathedral (1558-72), Lichfield Cathedral (1559-61) and Ely Cathedral (1567-85). He was important in the legal world, most notably in 1567, when he established the London premises of Doctors’ Commons (a society of civil lawyers).

His was a time of great upheaval in the University, as a result of the turbulent years of the reformation, which saw – within a generation – England’s separation from the Roman church under Henry VIII, a period of extreme Protestantism under his son Edward VI, a return to Catholicism with Mary I and finally the restoration of Protestantism with Elizabeth I. To succeed in this troublesome period one had to be very careful, and Harvey’s immediate predecessor as Vice-Chancellor (Andrew Perne) was an extreme example of this: he changed his allegiance so frequently that Cambridge wits, it was said, translated ‘perno’ as ‘I turn, I rat, I change often’. Harvey was himself involved in seeking out banned books in the University during Mary’s reign, as ‘Commissioner for detection of heretical books’ in 1556, but he was presumably well-regarded enough to be offered the Mastership in the year of Elizabeth’s accession. It is unknown where the volume went after Harvey’s death in 1585, but in 1913 it was bought by Stephen (later Sir Stephen) Gaselee – then Pepys Librarian at Magdalene – on Gustave David’s market stall in Cambridge. Gaselee included it as no. 100 in his List of the early printed books in the possession of Stephen Gaselee (Cambridge, 1920) and eventually gave it to the UL in November 1934, just two weeks the official opening (by King George V) of the present building. He eventually gave a total of 311 incunabula and remains the Library’s second most prolific donor of fifteenth-century printed books, after King George I (whose gift of Bishop Moore’s library in 1715 included 470 incunabula).

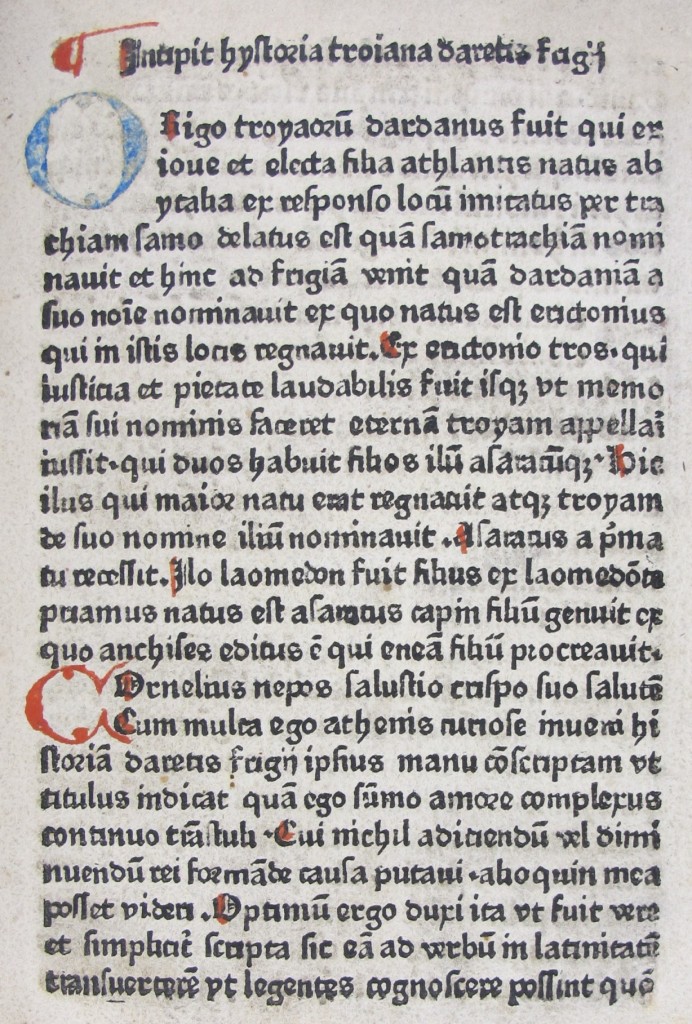

The third and final book I would like to discuss is the earliest of the three, both in terms of its date of printing and the text it contains. It is a slim volume of about twenty leaves, containing a history of Troy by the mysterious ‘Dares Phrygius‘, whom Homer tells us was a Trojan priest. Although the text is traditionally linked to the pre-Homeric period – and therefore to the very origins of European literature – the version of the text printed here is one which was ascribed to the 1st century BC writer Cornelius Nepos (though it is more likely to have been compiled five centuries later) and which circulated widely in the medieval period. The UL’s copy was printed in Cologne by an unknown printer known simply as the ‘Printer of Dares’ at an unknown date not after 1472. By 1659 it was in the Benedictine Abbey of Georgenberg at Kärnten (Austria) and at some point, probably in the first half of the nineteenth century, it was acquired by Edward Vernon Utterson (d. 1856), who had it bound with his arms in gilt on the boards. Utterson was educated at Eton, matriculated at Trinity Hall in 1797, took his bachelor of laws degree in 1801 and was called to the Bar in 1802, becoming a barrister at Lincoln’s Inn. He was elected a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1807 and was one of six Clerks in Chancery from 1815 until 1842. He had a great love for books – centred around English literature, and Italian, Spanish and French chivalry-romances – and was one of the eighteen founder members of the Roxburghe Club in 1812, the world’s premier bibliophile society. He did not just collect early books, but edited and printed facsimiles himself: at his home (Beldornie Tower) on the Isle of Wight – he set up a printing press, called the Beldornie Press, which operated for a few years early in the 1840s. Many of his productions were printed in extremely limited editions and are consequently exceedingly rare today. The UL holds just one of these, which was printed in sixteen copies: a facsimile of Samuel Rowlands’ Good newes and bad newes, originally printed in 1622. Utterson had a considerable library, from which the ‘principal portion’ was auctioned at Sotheby’s in April 1852 (perhaps a result of the death of his wife in 1851).

Among the 1950 lots were a fourteenth-century manuscript of Rolle’s Pricke of conscience, a fifteenth-century manuscript of Lydgate, Caxton’s Recuyell of the histories of Troye (the first book printed in English), the first edition of Shakespeare’s Sonnets (1609; now in the Folger Shakespeare Library and one of just five copies to survive) and the 1623 ‘first folio’ of his plays. After Utterson’s death, aged 80 in the summer of 1856, the remaining books were sold at Sotheby’s on 20 March 1857, where this edition of Dares Phrygius was lot 480 (sold to the bookseller Bohn for £2 14s). At an unknown point after that sale it was bought by Henry Bradshaw, University Librarian at Cambridge from 1867 until his death in 1886 – and a great collector for the Library of early printing – who presented it to the UL in 1885.

With just three volumes we have traversed nearly five centuries of collectors and collecting in Cambridge and seen the ways in which members of Trinity Hall have made their mark in the world of books and – noticeably – the law. These books are all to be found in the University Library’s Rare Books Department, where they may be consulted by anyone with a Library Card.

![Utterson's arms on Inc.5.A.4.4[410]](https://specialcollections-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Utterson-894x1024.jpg)