His royal favour: science, communication and livres d’apparat.

The current exhibition His royal favour: The books that built the Library celebrates the outstanding collection of John Moore, Bishop of Ely, (1646–1714). Bought by King George I after Moore’s death, the collection was offered to Cambridge University Library in September 1715. One of the books on display is a copy of Memoir’s [sic] for a natural history of animals, containing the anatomical descriptions of several creatures dissected by the Royal Academy of Sciences at Paris, published in London in 1688.

Claude Perrault (1613–1688)

Memoir’s [sic] for a natural history of animals, containing the anatomical descriptions of several creatures dissected by the Royal Academy of Sciences at Paris

London: J. Streater, 1688

M.14.41, pp. 2–3 (Royal Library)

The Memoir’s was a translation, produced by the Royal Society of London of an extraordinary work, printed by the Imprimerie royale in Paris in the 1670s: Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire naturelle des animaux. The two volumes of the publication represent a real 17th-century scientific “communication project”.

Under the supervision of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Louis XIV’s Minister, a team of the best artists and printmakers working for the Cabinet du Roi had been commissioned to produce a number of detailed illustrations of the scientific works undertaken under royal patronage. Some of these series of prints were published as books. These were not commercialised, but offered as prestigious gifts to foreign princes and ambassadors. One of their functions was to broadcast the work of one of the newly-created French scientific institutions. The Académie des Sciences had been founded in 1666 by Louis XIV, once more at Colbert’s suggestion, to encourage French scientific research, including zoology and anatomy. Some of the descriptions of the animal studied by the Academie had been published between 1667 and 1669 (Description anatomique d’un cameleon, d’un castor, d’un dromadaire, d’un ours, et d’une gazelle, for instance, published in Paris in 1669, found at the classmark K.8.47 in the University Library, is attributed to Perrault by Barbier in Dictionnaire des ouvrages anonymes), but the first volume of the presentation copy of Histoire des animaux appeared in 1671, with the description of 13 different species of exotic animals. (classmark Rel.aa.67.1 in the University Library). A second volume, published five years later, added the descriptions of 16 more species. (Rel.aa.67.2)

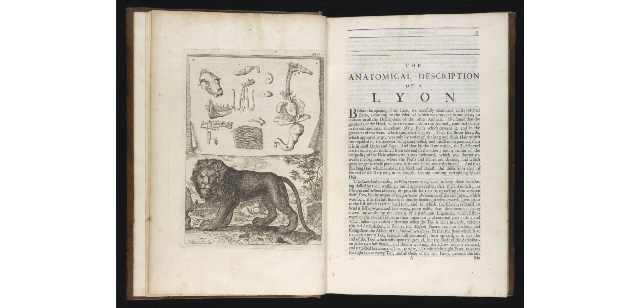

The books were bound in a typical royal presentation fashion: red morocco leather, with a gilt centrepiece with the arms of the French King, framed by decorations and borders of dentelles and blind rolls. In the format of elephant folios, they are beautifully illustrated with vignettes and cul-de-lamps decorations, and full-page zoological plates, showing the animal and its organs on the top half and the live animal in its natural habitat on the bottom half of the page.

The title page listed no author but displayed a royal symbol with a crown and fleurs-de-lis: this was, before everything else, a royal enterprise. The anonymous author, Claude Perrault (1613-1688), was one of the founding members of the Académie des Sciences, and the brother of the famous author of fairy tales Charles Perrault. Claude’s rigorous descriptions and his meticulous scientific method were seminal for the development of comparative anatomy in France. The first volume is also bound with Jean Picard’s La Mesure de la Terre, a 30-page essay where Picard described his material, and exposes his measurement of the arc of the meridian running between Paris and Amiens. Some of his very precise calculations were used by Newton to verify his own theory of universal gravitation. Most of the illustrations were the work of Sebastien Leclerc (1637-1714), a succesful engraver and a protégé of Colbert. The frontispiece to the first volume shows a visit, at that time still imaginary, of the King and Colbert to the Academy, where a group of academicians are gathered to watch the dissection of a fox. In the background, there is a scene depicting some architectural work in progress – Perrault was also a famous architect, celebrated for the construction of the East Wing of the Louvre.

Frontispiece of the Memoires …, a fictitious visit of the Academie by King Loui XIV and Colbert, and a showcase for various French artistic and scientific accomplishments.

A true livre d’apparat, the French volumes of the Mémoires… were indeed extremely hard to obtain. Alexander Pitfeild, who translated the books into English in 1688, noted that most of the copies were given away to “persons of the greatest quality,” and that very few copies were actually available. Moore, obviously a “person of the greatest quality”, owned a copy of the original as well as the English translation, both of which are now kept in Cambridge University Library Royal Collection. The immense size of the Mémoires… (it is more than half a metre high) means it is too large to be displayed in an exhibition case.

Don’t forget: His royal favour, which marks the 300th anniversary of the gift by George I to the University of Cambridge of 30,000 books and manuscripts that transformed the University Library for ever, is on display until