A. N. L. Munby’s Christmas ghost stories

A. N. L. ‘Tim’ Munby (1913-1974), who has featured on these pages before, has at least two connections with Christmas. Most importantly, he was born on Christmas Day (in 1913), the origin of his second Christian name ‘Noel’. But two of his ghost stories – one of which first saw print at Christmas 1944 – are also linked to this festive season.

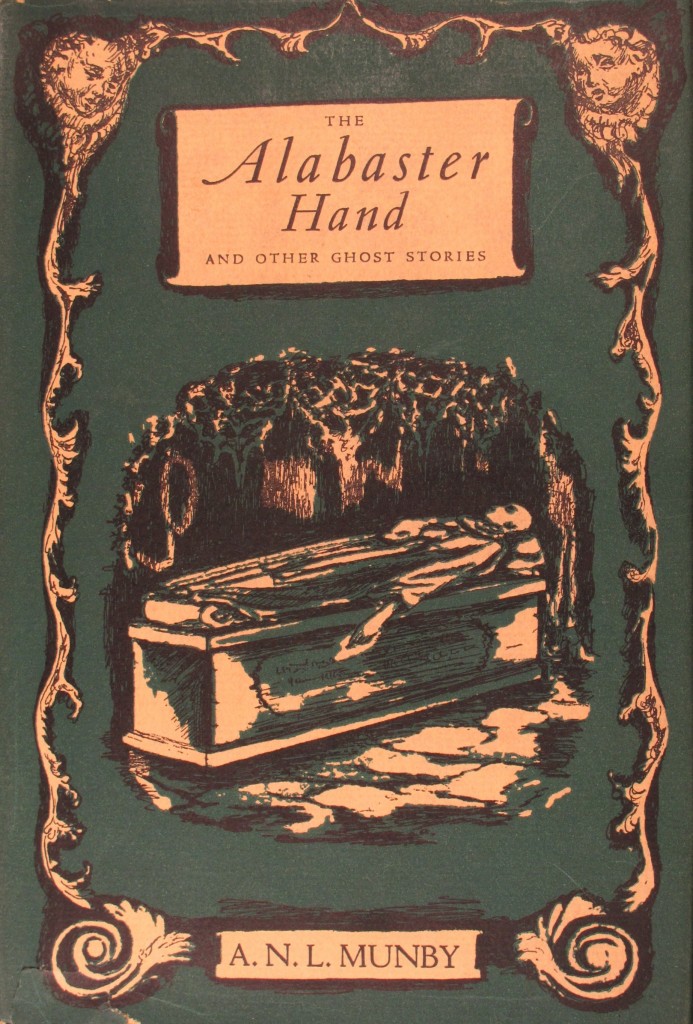

As Librarian of King’s College for nearly thirty years (1947-1974) Tim Munby was a well-known face around Cambridge. The legacy of his work is all around us, from the core of his personal library at University Library to the significant collection of authors’ papers he built up in his own college library, which continues to be added to. His school years were spent in Bristol, before three years as an undergraduate at King’s (1932-1935), a stone’s throw from Gustave David’s stall on the market where his bibliographical skills were honed. Upon graduation Tim became a bookseller in London, working for the well-known firm Quaritch and at Sotheby’s auction house. But in 1940, his life changed significantly when – having joined the Territorial Army some years before – he was sent to France to defend Calais from approaching German tanks. He was soon captured and spent the rest of the war as a German prisoner of war, first at Laufen (1940-41), then Warburg 1941-42) and finally Eichstatt (1942-1945). Life in an officers’ camp was not extremely oppressive, but was tedious and frustrating, and the men had plenty of time to amuse themselves, with books, lectures and theatrical performances. Tim Munby used his time productively and in February 1941 recorded in his diary that he was ‘writing numerous short stories’ – perhaps ghost stories – which would appear in print as The alabaster hand and other ghost stories in 1949. These were written along the same lines as those by his fellow Kingsman, M. R. James (Provost 1905-18), who favoured antiquarian themes often centred around books and libraries. Furthermore, James often read his ghost stories to friends and colleagues in his rooms at King’s at Christmas. Before they were collected together in 1949, several of Tim’s ghost stories first appeared in Touchstone, a prisoners’ magazine printed at the camp in Eichstatt where he was kept between 1942 and 1945. Tim’s copies were presented to the Library by his wife Sheila after his death.

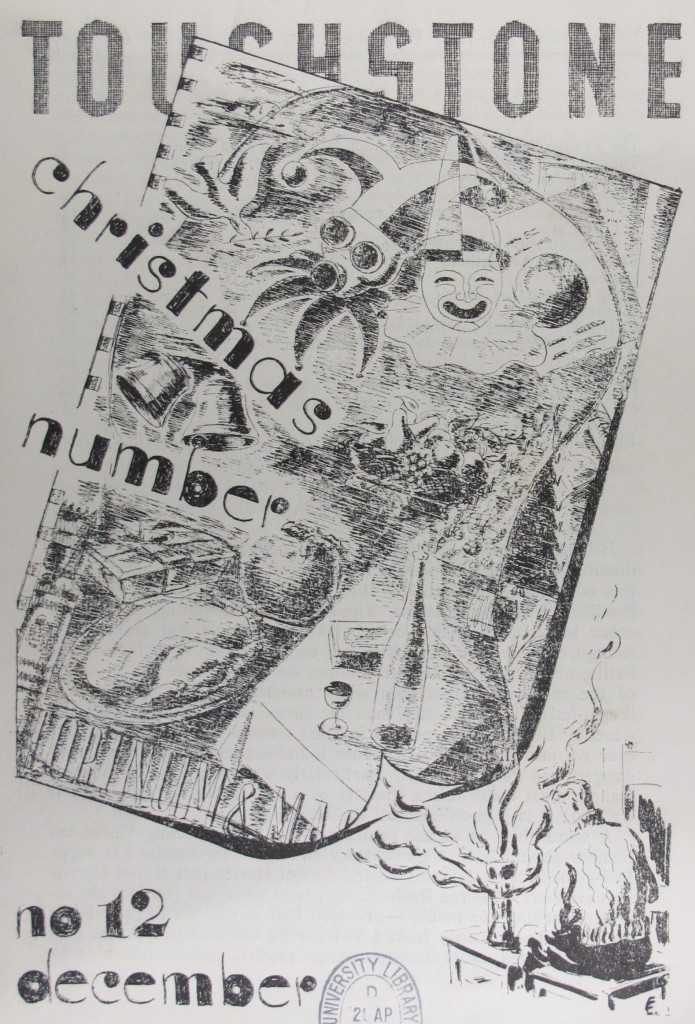

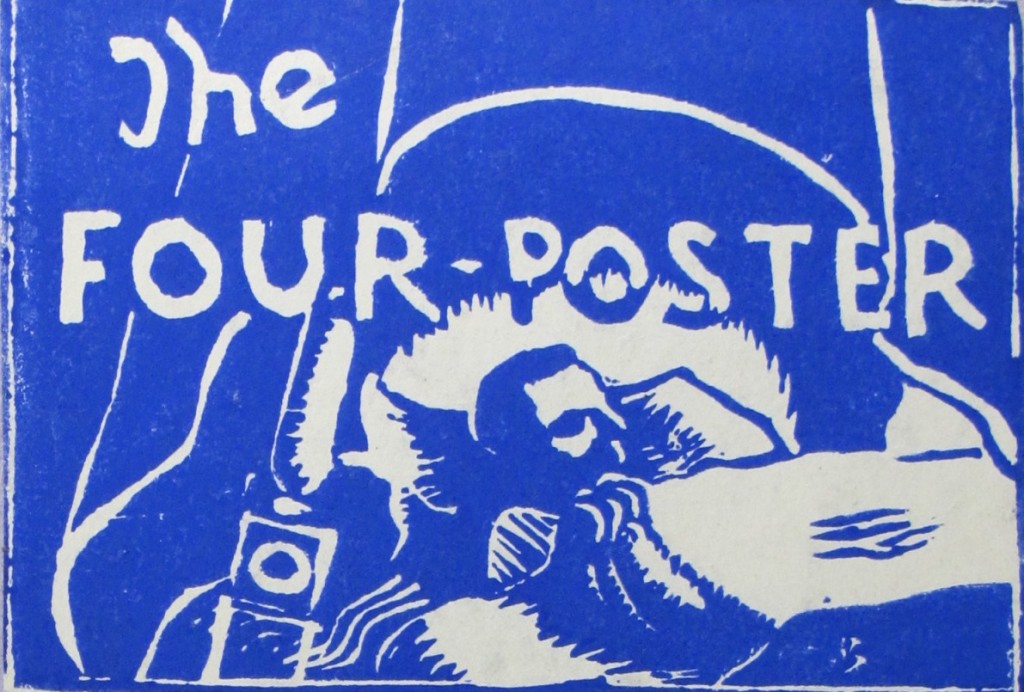

Fifteen issues of the magazine appeared, between autumn 1943 and March 1945, and the twelfth – the Christmas number for 1944 – contained his first printed ghost story. Entitled ‘The Four-Poster’ it concerned spooky goings-on at a country house. Somebody sleeping in the eponymous bed is plagued by a nightmare, in which he finds himself in a churchyard, witnessing a group of men snatching a body from a grave. Afterwards he encounters the shrouded body: ‘…a pair of yellow desiccated arms came up and gripped him behind the neck, forcing his face down to meet its own’. Another occupant of the bed later dies while sleeping in it and it is discovered, when the original eighteenth-century bill for the bed is found, that the bed-curtains had been used in the 1790s to wrap the body of a hanged convict. The maker of the bed was discovered to have been involved in body-snatching, and evidently used the shroud to make the curtains, which had long harboured ‘some baneful influence’. The scene is described well by Munby, who speaks of a high wind which ‘made the hangings of the bed rustle and flutter…[giving] the illusion of people whispering in the room’. The story was illustrated by Robin Bagot (1914-2000), a fellow prisoner born a year after Tim, and who attended Eton and Trinity College. He provided an image of the original bill for the bed’s construction, and one of the bed itself, at the moment of the discovery of the dead man. Shrouded in darkness, light spills in to the room from outside illuminating the prostrate figure on the bed. Along with Munby’s skilful way with words, the image helps to conjure up a quite terrifying story. Twenty-five inscribed presentation copies of the story were printed off separately, and bound in paper covers illustrated with another view of the bed and its unlucky inhabitant. Tim gave a copy to Cambridge University Library in 1960, and there are copies at King’s College Cambridge (ANLM/6/2/1 item 21) the in the Bodleian (which seems to have belonged to the ornithologist John Buxton, also imprisoned at Eichstatt).

The second Christmas-themed story is Munby’s ‘A Christmas Game’, which did not appear in Touchstone, but first saw print in the collected edition of 1949, sadly un-illustrated. It is one of his most terrifying, and centres around the narrator’s father, who brings home an old friend (Mr Fenton) for Christmas. On the evening of Christmas Day itself, ‘the lights were extinguished and a screen was drawn in front of the fire’, so that the father could tell the family a ‘horrid tale’, aided by the son who handed round the room objects which might aid the imaginations of those listening. The story concerned a traveller in North America who was set upon by local Natives, who removed his scalp (at which point in the story the son passed round an old piece of fur rug, greeted with ‘much giggling and with exclamations of disgust from my aunts’) and gouged out his eyes. These were represented by two peeled grapes, but when handed to Mr Fenton, they induced ‘an inarticulate half-strangled cry of disgust’ before he threw them in the fire, where the narrator – just for a second – sees that they had become real eyes. That night a strange figure is seen in front of the fire, scrabbling in the grate for the eyes, and soon after, Mr Fenton dies of fright in his bed after seeing a figure (invisible to everyone else) in his room.

Fourteen of Tim’s ghost stories were gathered together and printed in 1949, by Elliott Viney (another fellow prisoner), and summaries of each are available online here. The collection appeared in paperback in the 1960s and ’70s and the stories remain popular today, especially at this time of year: a new edition appeared in 2013, Munby’s centenary year, when a conference (the proceedings of which have just been published) was held at King’s College in his memory.

There was at least another surviving copy of the limited edition of the ‘Four Poster Bed’, which of course belonged to the printer Elliott Viney (1913-2002) and was shown to me by him in c.2000, and had a page of Tim Munby’s manuscript and an illustration by O.R. Bagot tipped in. I have searched for Robin Bagot’s copy at Levens Hall in Westmorland but never found it; the Bodleian copy must almost certainly have belonged to John M. Buxton (1912-1989), Fellow of New College, and whose run of the camp magazine ‘Touchstone’ is also in the library in Oxford.

Elliott told me that they had the use of the Bishop’s printing press at Eichstatt, and a good supply of Swedish paper, which accounts for the excellent quality of their products.

Captain Munby’s exploits at Calais are told in military histories of that folorn hope, with his men led into the French Fort Nieulay prior to its final bombardment and surrender. There is another curiosity of their literary endeavours in that Munby’s ‘Lyra Catenata’ were only printed in 1948 in a limited edition (by Viney); but John Buxton’s volume of verse written in captivity ‘Such Liberty’ was printed by Macmillan in 1944, though with no clear explanation of how they obtained his copy. It all rather pointedly underlines the bizarre nature of their captivity, trapped in the endless tedium of a kind of public school in exile, compared with the unspeakable experiences of prisoners elsewhere, and finding themselves at the end of the war having done ‘nothing’ but survive.