Malthus in Cambridge

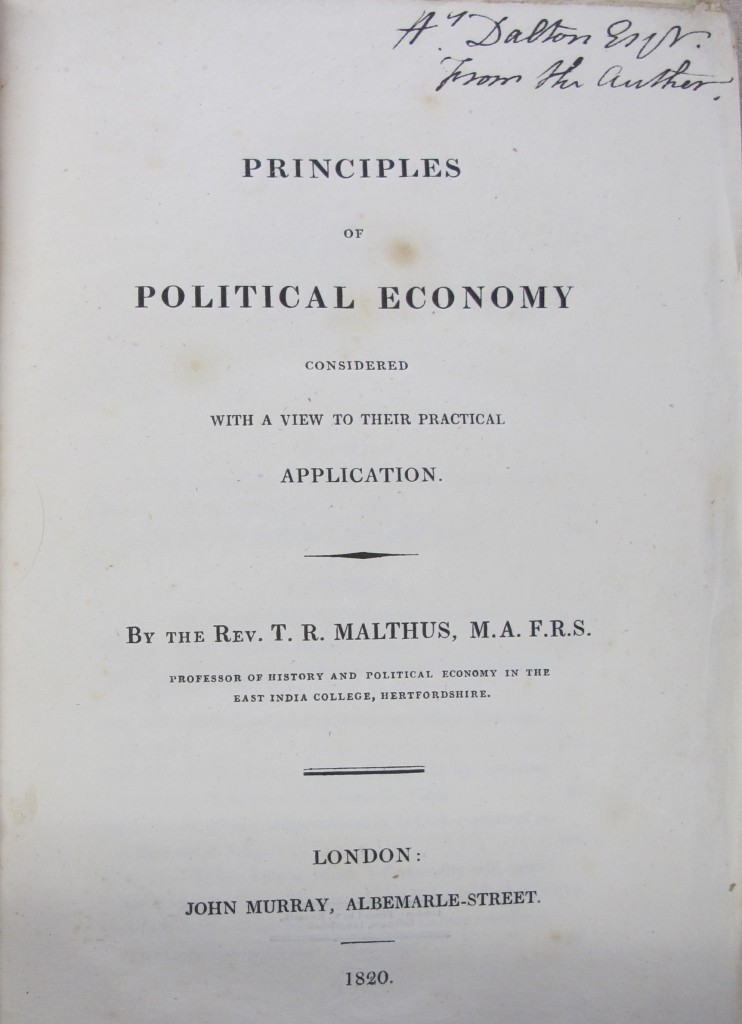

On this day in 1766 – 250 years ago – was born Thomas Robert Malthus, for whom bells rang out in Cambridge yesterday. A scholar, cleric and political economist, Robert (his preferred name) studied at and became a fellow of Jesus College Cambridge, where his family library (which I had the pleasure to catalogue online in 2011) has been preserved since 1949. The library contains about 2000 volumes and was begun by his father, Daniel Malthus (1730-1800), when the family lived at The Rookery, a large house just outside the village of Westcott (near Dorking in Surrey). Robert added greatly to the collection, adding many works relating to his work on political economy, which he used when writing his magnum opus, the Essay on the principle of population, first published in London in 1798. The University Library holds three copies of the first edition, including one in its original blue paper boards which came to the Library in 1868 with the library of Professor George Pryme (the first lecturer on political economy at Cambridge, in 1816) and another in 1982 with the library of Sir Geoffrey Keynes, brother of the economist Maynard Keynes. But probably the most significant copy of Malthus’ work in the University Library is a copy of his 1820 Principles of political economy which, until 1949, formed part of the Malthus family library. In that year, before the library was sent to Jesus College, the descendant of the family who was at that time its custodian – Reginald Bray – gave this copy to the Marshall Library of Economics in Cambridge – via the economist Piero Sraffa – from where it was eventually sent with other rare material to the University Library.

Malthus spent a good part of his career at Cambridge, matriculating at Jesus College in 1784 (on the advice of his tutor Gilbert Wakefield, also a Jesuan) and taking his BA in 1788. He was a fellow of the college 1793-1804, and from 1805 until his death was Professor of History and Political Economy at what is now Haileybury and Imperial Service College (near Hertford).

He was also a man of the cloth, serving as curate of Albury (Surrey) and rector of Walesby (Lincolnshire). His work on political economy, represented by his first great work – An essay on the principle of population – influenced the law concerning poverty and unemployment. In it he argued that, since population multiplies geometrically and food arithmetically, the population will eventually outstrip the food supply. His work would go on to inspire later economists, among them two other great Cambridge men: Charles Darwin and John Maynard Keynes (whose own library is now at King’s College). The Essay was reprinted six times by 1826, during which time he published a pamphlet entitled Observations on the effects of the Corn Laws (1814) and, as we have seen, Principles of political economy (1820).

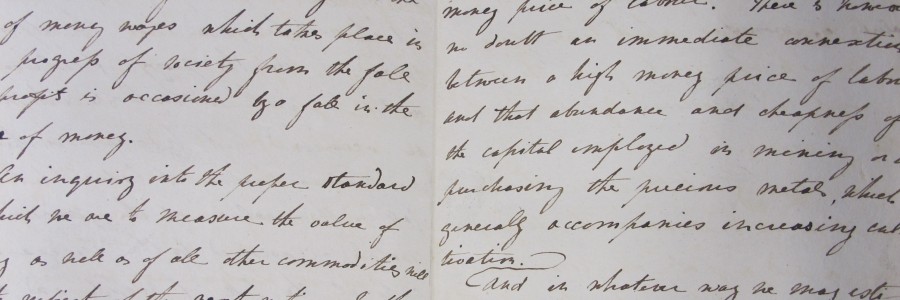

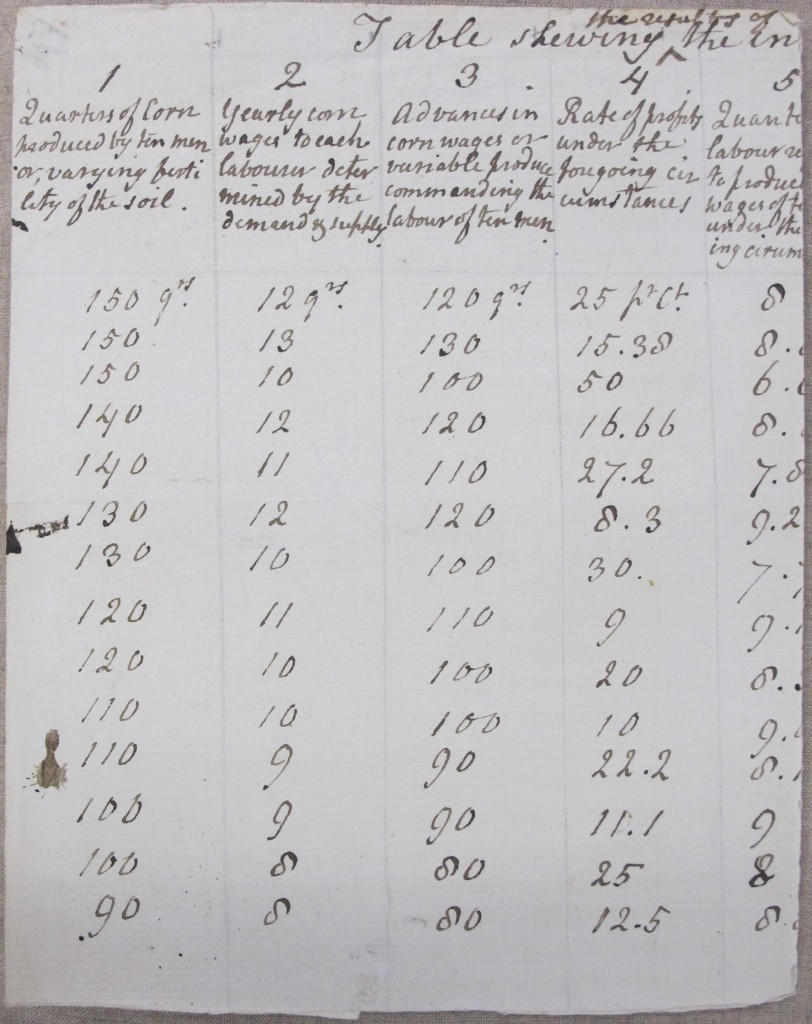

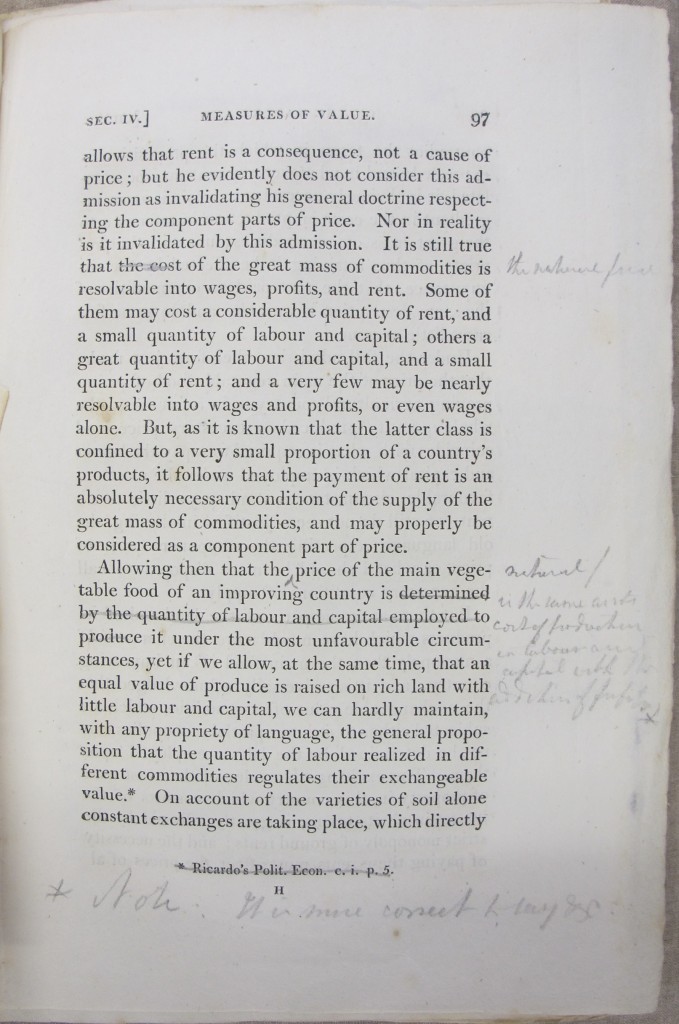

Malthus’ heavily annotated copy of this, now in the University Library, is now in rather poor condition, but its printed pages are covered in Malthus’ pencilled notes, and there are many extra leaves of notes in ink slipped inside (as in the example at the head of this post), all in his own hand. In either 1820 or 1821 the author presented it – as we see from his inscription on the title page – to Henry Dalton, brother of Jane Dalton (herself a cousin of Robert’s father Daniel), who inherited Jane’s substantial library at her death in 1817 and who died in 1821. Malthus himself died suddenly in Bath in 1834 and is buried in the Abbey there.

The significance of the volume was realised early on for it was used for Henry allowed it to be used for the posthumous 1836 second edition, which the title page proclaimed was ‘with considerable additions from the author’s own manuscript’. But after this it seems to have fallen into obscurity with the rest of the Malthus Library until 1928, when a note inside tells us it was rediscovered library at Dalton Hill – the family home. In that year the manuscript notes were copied by the Scottish political economist James Bonar, whose Malthus and his work appeared in 1885. Another slip of paper reveals that twenty years later the volume was given by Reginald Bray to the Marshall Library (on 7 July 1949), and a letter from Bray to Sraffa ten days later confirms that the separate pile of manuscript notes by Malthus, evidently slipped into the book, had become separated. These were evidently reunited with the book, and the two now sit within a conservation box in the University Library. The notes and letters alongside the book turn it into a veritable archive of Malthusian scholarship and, in this 600th anniversary year of the University Library, its long journey to the University Library reminds us of Malthus’ importance to generations of scholars, not only in Cambridge, but more widely.

Pingback: Malthus in Cambridge | Quincentenary Library Blog