The first slide rule: a discovery in the Macclesfield Collection

Guest post by Boris Jardine.

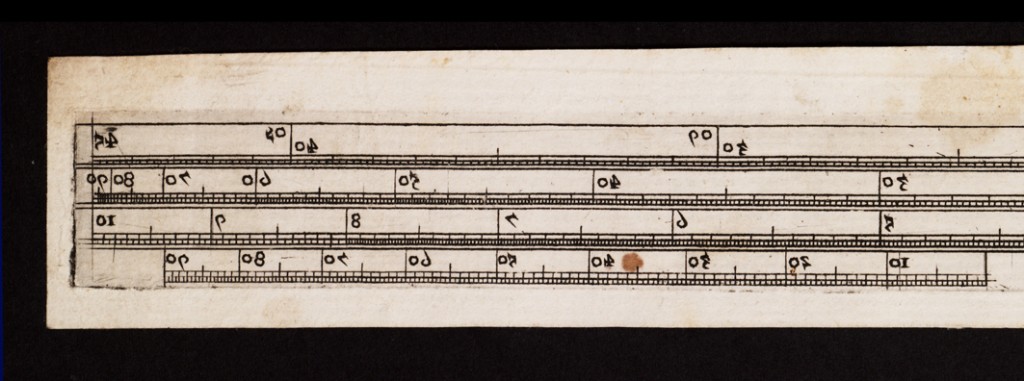

Slide rules dominated the practice of mathematics from their invention in reign of King Charles I to their sudden, electronic-calculator driven demise three centuries later. If you go up into your attic you might even find one discarded by a relative who had just opened a box marked ‘Casio’ or ‘Texas Instruments’. But slide rules were once revolutionary, changing the way that everything from astronomy to brewing was done. They are one of the landmarks in the history of computing – today a matter of gaming and databases but historically just methods of speeding up calculation. Until now the oldest known slide rule was the one made by Robert Bissaker in 1654, held at the Science Museum, London. But the slide rule was invented more than twenty years before that, by the mathematician William Oughtred. Now, a discovery in the Manuscripts Room at Cambridge University Library has given us not just an earlier slide rule – but the very first.

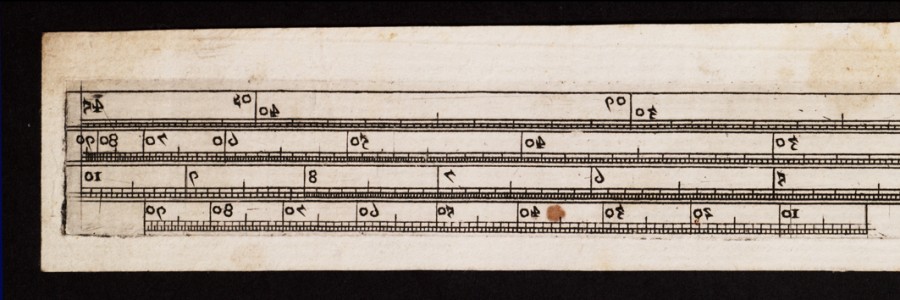

What’s remarkable about the UL rule – and the reason it’s in the UL at all – is that it’s made of paper. It is preserved along with a letter from Oughtred to the craftsman Elias Allen, sent on 20 August 1638 – part of the Macclesfield Collection. In the letter Oughtred describes the slide rule and says that he “would gladly see one of [the two parts of the instrument] when it is finished: wch yet I never have done”. So even though the letter itself dates from 1638, many years after he invented the slide rule, Oughtred had still not got around to having one made. We have to speculate about what happened next, certainly Allen made the two-foot rule, inked it up as if it were a printing plate and then printed an image of it. Was this to send to Oughtred as a prototype? Was this kept as a record for his workshop? Either way the brass instrument is long since lost but the paper version survives – a concrete record of the very first slide rule.

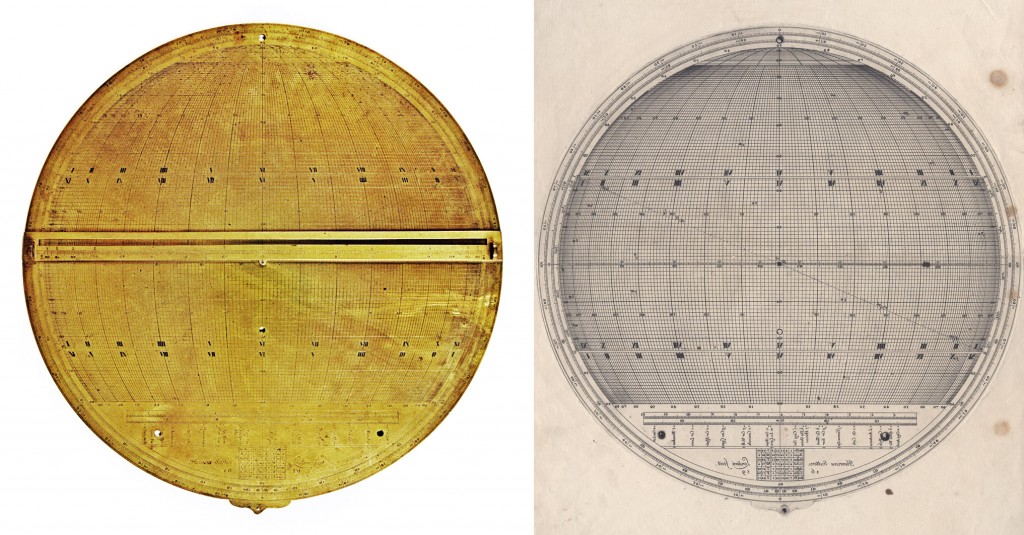

The first thing to notice about the slide rule is that the numbers are all backwards. Most prints are made from reversed printing plates, but the Oughtred-Allen slide rule was printed directly from a ‘normal’ instrument – a practice that may sound strange but was in fact relatively common in the seventeenth century. Allen seems to have been its pioneer – making reverse-printed records of instruments that had taken him a long time to engrave and that, if sold, he would perhaps never see again. Every surviving reverse print is of something important: the first slide rule, a difficult piece of engraving, an important commission. Here, for example, is an astrolabe by the master-craftsman Henry Sutton, alongside the print made directly from it. The beautifully engraved lines make up a grid that depicts the heavens – the course of the Sun through the year and the locations of stars and planets. It is easy to see why Sutton or someone associated with him would have wanted to make a record of this remarkable instrument.

Astrolabe by Henry Sutton, dated 1659, and the reversed print made directly from it. Images © the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford, inv. nos. 51786, 56420.

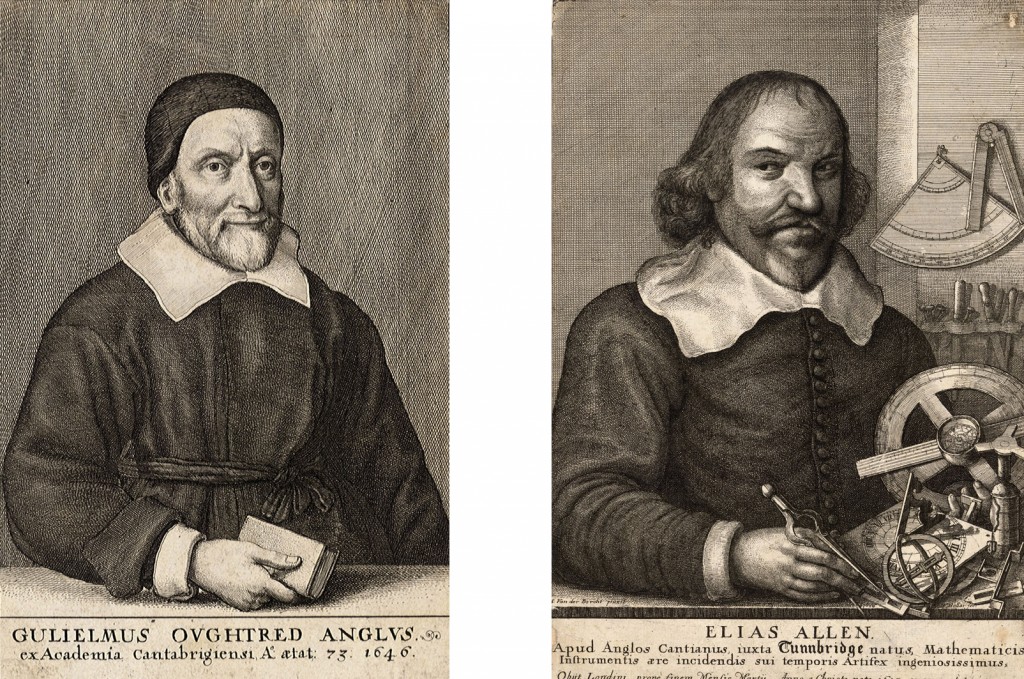

Returning to the UL slide rule, why might it have taken Oughtred so long to have his new invention made by Allen? He is known to have thought up the principles of the slide rule in the 1620s, and he published an account of the instrument in 1633. One possible reason for the delay can be inferred from looking at the portraits of both men, above. In one we see a bookish, sober scholar, in the other a worldly, cosmopolitan businessman. Oughtred invented instruments for his own use, and for the use of those already expert in the underlying mathematics. Why? Because, in his own words, “the true way of Art is not by Instruments, but by Demonstration: and that it is a preposterous course of vulgar Teachers, to begin with Instruments, and not with the Sciences, and so in-stead of Artists, to make their Scholars only does of tricks, and as it were Juglers”. The “true way”, thought Oughtred, was by the study of books like his Clavis Mathematicae [Key of Mathematics], which could act like “Ariadne’s thread”, guiding its readers through the “intricate Labyrinth” of the subject. This is why a copy of the Clavis is the only additional detail in Oughtred’s portrait. Allen, meanwhile, was a successful artisan whose business relied on meeting demand for an ever-increasing range of instruments. Hence the 1638 letter from Oughtred to Allen begins, “I have here sent you directions (as you requested me being at Twickenham) about the making of the two rulers”. Oughtred, perhaps fearful of turning the capital’s mathematical practitioners into “doers of tricks”, only thought of having his invention made when prompted by Allen, as much as a decade after the moment of inspiration.

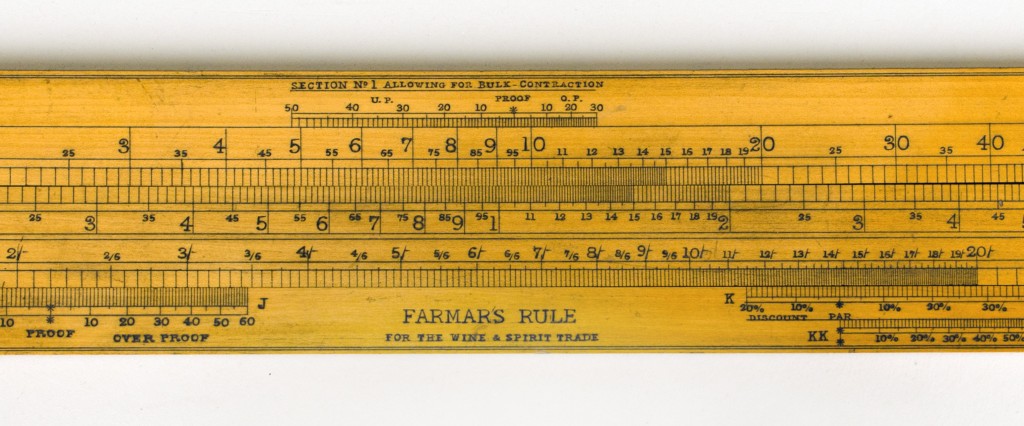

Doers of tricks or not, mathematicians and workers in a wide range of fields have been grateful for Oughtred’s invention. As time went on specialist slide rules were developed for every subject imaginable, fit for brewers, distillers, chemists, printers, gunners, astronomers, photographers, musicians and even sewage inspectors. During the Cold War slide rules were even made to calculate radiation exposure over time. Though eventually replaced by the pocket calculator, the slide rule is one of the most important instruments in the history of computing, and the UL printed rule gives us a glimpse of the moment it was first made.

‘Farmar’s Rule for the Wine and Spirit Trade’ (detail). Image © the Whipple Museum of the History of Science, Cambridge, Wh.2330.

Dr Boris Jardine was Munby Fellow in Bibliography at Cambridge University Library 2014-15. In March 2016 he will begin a Leverhulme Early-Career Research Fellowship with the title ‘The Lost Museums of Cambridge Science, 1865–1936’.

Really fascinating post about a truly great discovery

Pingback: Whewell’s Gazette: Year 2, Vol. #32 | Whewell's Ghost

Pingback: What We’re Reading: Week of Feb. 27 | JHIBlog

As a slide rue historian and a board member of the Oughtred Society, I find this article on Oughtred’s slide rule pattern for his engraver – Elias Allen – to bee a very important discovery. This is the first presentation of Oughtred’s slide rule known to me. Oughtred was protective of his design, in fear that his competitor – Richard Delamaine – would steal his idea.

However, this is not the ealiest slide rule (or slide rule scale design) known. The British Museum has in its collection a very important circular slide rule with a spiral scale executed on brass disk by Johannes Hulett in 1635. The disk is engraved near its center with: ‘Johannes Hulett Circulariter sed Vitato Circuitu’ and dated 1635. It has a 10 turn spiral calculating scale with a scale length of about 3.8 meters. . . .Johannes Hulett was a 1633 graduate on New Inn Hall (now St. Peter’s College at Oxford University). Hulett lived in Oxford where he was an instrument maker and a teacher of mathematics for private students. It is known that both Oughtred and his forner student turned compeditor, Richard Delamaine, designed circular slide rules by 1630. Since Hullett resided in Oxford and Oughtred in Cambridge and Delamaine in London, this is a difficult issue to sort out. Perhaps there are more letters deep in the files in Cambridge and Oxford that will help sort this out.

Being a Yankee, I am not familiar with the connections between Oxford and Cambridge in the 1630s.

Perhaps Boris Jardine can dig deeper into the Special Collections at Cambridge University to sort out possible connections between Oughtred, Delamaine and Hulett.

Hi Ed,

Many thanks for the comment — this adds a lot to the story. You’re absolutely right that there are earlier uses of the logarithmic scales on instruments, and that the principle of the slide rule is present in the Hulett instrument. You probably also know of the Allen ‘circles of proportion’ at the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford, circa 1634: http://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/collections/imu-search-page/record-details/?TitInventoryNo=40847 (incidentally Anthony Turner recently pointed out to me that a print made from this instrument survives in the collection at Marsh’s Library in Dublin).

The specific principle that I think is genuinely novel with the 1638 paper rule is the application of two logarithmic scales directly to one another. This had been proposed by Oughtred in two 1633 publications, but the earliest example known was the 1654 rule at the Science Museum. So I feel the UL paper rule still counts as a first — though again I think you’re correct to qualify this with reference to the circular rules.

As for Hulett, I wonder… the fact that the Oxford Circles is also an Oxford instrument is particularly intriguing, and I’ll certainly try to follow up these highly obscure characters!

Many thanks,

Boris

A vernier device for more precise reading of spiral scales was invented by Oliver Steffens.

Thank you for this! Liam Sims, Rare Books Specialist.

Very fascinating!

Your will find more information on analog calculating devices in my two-volume-book (available in German and English):

Bruderer, Herbert [2020a]: Meilensteine der Rechentechnik, De Gruyter Oldenbourg, Ber-lin/Boston, 3. Auflage 2020, Band 1, 970 Seiten, 577 Abbildungen, 114 Tabellen, https://www.degruyter.com/view/title/567028?rskey=xoRERF&result=7

Bruderer, Herbert [2020b]: Meilensteine der Rechentechnik, De Gruyter Oldenbourg, Ber-lin/Boston, 3. Auflage 2020, Band 2, 1055 Seiten, 138 Abbildungen, 37 Tabellen, https://www.degruyter.com/view/title/567221?rskey=A8Y4Gb&result=4

Bruderer, Herbert [2020c]: Milestones in Analog and Digital Computing, Springer Nature Switzer-land AG, Cham, 3rd edition 2020, 2 volumes, 2113 pages, 715 illustrations, 151 tables, translated from the German by John McMinn, https://www.springer.com/de/book/9783030409739

Thank you for this!