Castles in the air: two works of Renaissance and Baroque Iberian poetry

Thanks to a recommendation of Dr Rodrigo Cacho, Reader in Spanish Golden Age and Colonial Studies, the Rare Books department of Cambridge University Library has recently acquired two rare volumes of seventeenth-century poetry, both printed in Lisbon.

These two books represent a very important addition to the early modern Iberian poetry collection of the UL. Sá de Miranda (1481-1558) and Manuel de Galhegos (1597-1665) –often spelled ‘Gallegos’– were Portuguese authors who composed literary works in their own language and also in Spanish. Both authors represent two different moments, the Renaissance and the Baroque periods, in the literary and cultural exchange between Spain and Portugal during the 16th and 17th centuries. This link became stronger between 1580 and 1640 when Portugal was united to the crown of Castile after King Sebastian died without heirs and his uncle, Philip II of Spain, successfully imposed his dynastic claim. Several Portuguese poets also wrote in Spanish; one only needs to think of Luis de Camões and his production in both languages.

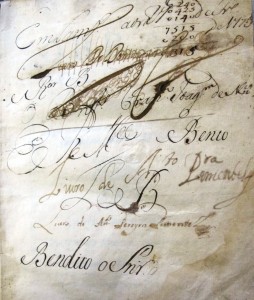

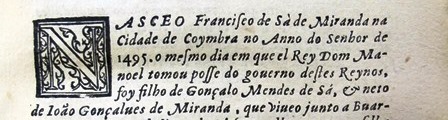

The first recent acquisition, As obras do doctor Francisco de Saa de Miranda, printed in 1614, is the rare second edition of the collected works of Sá de Miranda, who has been described by the scholar Aubrey Bell (1881–1950) as the “champion of humanism in Portugal”. The first edition had been published in Lisbon in 1595, but it was far from complete: this second edition includes the earliest biography of the author, and seventeen additional works. It is listed in the Manual del librero hispano-americano by Antonio Palau y Dulcet under the reference 283214. The UL copy is a quarto bound in contemporary limp vellum, with remains of ties; it presents several contemporary and later inscriptions, some of them scored, on the first flyleaf.

It is decorated with a woodcut vignette on the title page, and with woodcut initials and headpieces throughout the text.

Sá de Miranda is one of the most significant Portuguese authors of the Renaissance. His poems and plays contributed to the introduction of the new cultural wave that originated in Italy and pioneered, alongside Spanish poets such as Garcilaso de la Vega, the development of classicist metrics and genres: sonnets, elegies, epistles and pastoral poems.

The second edition of his works acquired by the UL is a stepping-stone in the canonization of Sá de Miranda. As previously mentioned, the volume contains a biography of the author (probably authored by the poet’s brother-in-law Gomes Machado de Azevedo) and adds more texts to the first edition published in 1595. The collection is organized by genre, beginning with the Italianate and classical forms followed by more traditional Iberian compositions, such as esparsas, cantigas and vilancetes. A final section is devoted to a selection of poems published for the first time. This 1614 edition displays the versatility and complexity of this author who stood at the crossroads of modernity and tradition, employing Spanish and Portuguese as well as learned Renaissance models and the popular ballads of the Middle Ages. Among Sá de Miranda’s works one finds sublime sonnets such as ‘O sol é grande, caem co’a [calma] as aves’, which contains a reflection on the passage of time and the absurdity of human existence, set in an all-to-familiar natural space which is picked apart by the poet:

The sun is large: the birds calmly descend

from the air in this season, which tends to be cold.

Oh, that the water that falls from above would stir me,

not from sleep, but from grave cares.

Oh things, all futile, all changeable,

what heart trusts in you?

Time passes, one day follows another,

much more uncertain than ships in the wind…

(English translation from Dreams of Waking: An Anthology of Iberian Lyric Poetry, 1400-1700, by V. Barletta, M. L. Bajus and C. Malik, Chicago/London, 2013, p. 99)

The same anguish can be found in his popular lyric, voiced in a more concise and intense fashion, as in his vilancete ‘Ó[s] meus castelos de vento’,

Oh, my castles in the air,

you have caused such sorrow,

how easily you have disappeared…

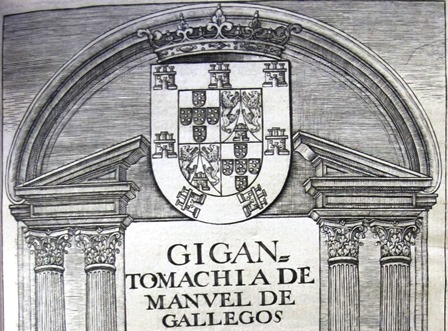

The second recently acquired volume is Gigantomachia by Manuel de Galhegos, printed in Lisbon by Pedro Crasbeeck, from a Portuguese printing dynasty originating in Antwerp, in 1628. Bound in eighteenth-century cat-paw sheep – a kind of binding that looks as if little inked feline feet had walked over its covers – it is the first and only edition of this Spanish heroic poem.

The engraved architectural title page shows the arms of the dedicatee, Dom Antonio de Menezes, a Portuguese general who fought in the Portuguese Restoration War.

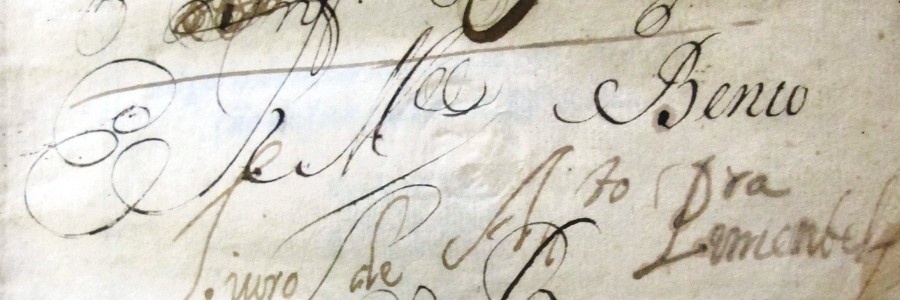

This copy has a rich provenance history, starting with an oval stamp of the library of the monastery of Alcobaça, once one of the most important monastic libraries in Portugal. (You can read more about it on Dr Elizabeth Evenden’s very informative Anglo-Iberian relations blog). It also contains the engraved armorial bookplate of the politician and historian A. Canovas del Castillo (1828–1897), on the verso of the front free endleaf.

There are two additional monogrammed bookplates, including one of Ricardo Heredia y Livermore, Conde de Benahavís, a Spanish bibliophile, whose library of more than 8000 volumes was sold in Paris in 1891.

The poetry of Manuel de Galhegos is embedded in the literary renovation that took place in the 17th century. After the works of the Spanish poet Luis de Góngora, Polifemo and Soledades, had achieved great recognition between 1610s and 1620s, a new aesthetic trend known as cultismo (‘learned poetry’) developed. In these poems, Góngora used obscure classical cultural references, complex syntax and a Latinate vocabulary. Polifemo and Soledades are extreme manifestations of baroque poetics, as well as displaying innovative trends to which the most prestigious genre of classical literary theory, the epic poem, had been subject after the Renaissance. Epic texts would now often be focused on mythological fables inspired by Ovid, and the format of such works would be much shorter than the usual lengthy structure of the heroic poem. This kind of text is often referred to as epyllion, and Góngora’s Polifemo was one of the most influential examples of this trend.

Galhegos’ Gigantomachia is his first known published poem and contains an extensive epyllion organized in five books which deals with the battle between the Giants and the Olympic Gods. The book also includes a shorter epyllion, a silva devoted to the myth of Anaxarete, which is often considered by scholars to be Galhegos’ masterpiece. Despite his works not reaching the level of dense and obscure complexity found in Góngora, there are clear links between Gigantomachia and Polifemo and Anaxarete and Soledades, respectively. The author highlights the influence of Góngora in the dedication ‘To the Reader’ found in the first pages of Gigantomachia,

My muse, oh learned reader, cries because she is aware that Luis de Góngora sings in his Polifemo using such an elevated style, erudition, new and ornate ideas, and with an energy which matches that of Virgil, to such an extent that no other author could be able to achieve the same quality when describing a giant nor the wittiest mind in the world could produce such an array of puns (¶3v).

Galhegos is true to his word; his Gigantomachia does not reach the same stylistic heights as Polifemo and Soledades. The text, however, is a much underrated poem of the Spanish canon and deserves more attention than it has received thus far. Despite its flaws, Galhegos’ work is an excellent example of the literary connections between Portugal and Spain as well as of the growth of baroque aesthetics. Epic poetry becomes more descriptive and erudite; filled with precious images and imaginative interludes:

The greenest emerald, the most inflamed

ruby generated by Phoebus in the Orient,

the best diamond, the shiniest pearl

cried out by the day in his tender infancy;

provided the ground on which she was standing

with such light that would lead you to believe

that, thanks to the reflections of their beautiful lights,

she was stepping victorious among stars. (I.21)

Sá de Miranda and Galhegos are two welcome additions to the Iberian collection of the UL. Both copies have interesting traces of use and provenance. The successive marks of ownership in Gigantomachia, in particular, are a fascinating insight into the fate of a book in Portugal and Spain from the early modern period to the private libraries of the greatest Spanish bibliophiles in the nineteenth century.

These books help us to rethink the Spanish and Portuguese early modern poetic canons, which have often been artificially isolated from each other. They also stimulate a revision of so called secondary authors, such as Galhegos, who in his time was celebrated by Lope de Vega in Laurel de Apolo (1630) as the ‘Lusitanic Orpheus’.

Rodrigo Cacho and Sophie Defrance