A binding for the organist John Bull (1562/3-1628)

The virtuoso composer, musician and organ builder John Bull (who probably spent some time at the University of Cambridge) died on this day in 1628. The University Library is also lucky to possess a volume which once belonged to him, on which more below. Little about his early life is known, but he was born in 1562 or 1563 (which we know from a portrait of Bull at Oxford, dated 1589, which puts him in his 27th year), possibly in Somerset, though London and Herefordshire have also been proposed. He had an illustrious early career in music, being appointed to the choir at Hereford Cathedral in 1573 and that of the Chapel Royal in the following year, before returning to Hereford as Organist in 1582. He received a degree from Oxford in 1586, a doctorate in 1592 and was, from 1596 (in addition to Organist at the Chapel Royal) the first Gresham Professor of Music in London, thanks to Elizabeth I herself, who is said to have admired his work. After her death he worked for James I but came to grief in 1607, losing his position after pre-maritally fathering a child with a lady by the name of Elizabeth Walter, whom he later married. By 1613 he had fled the country, having provoked the wrath of the Archbishop of Canterbury and James I with his adultery, and he was appointed Assistant Organist at Antwerp Cathedral in 1615, before becoming principal Organist in 1617. He was still in the city in 1628 and, though the date of his death is not recorded, it was probably 12th or 13th March, since he was buried on 15th.

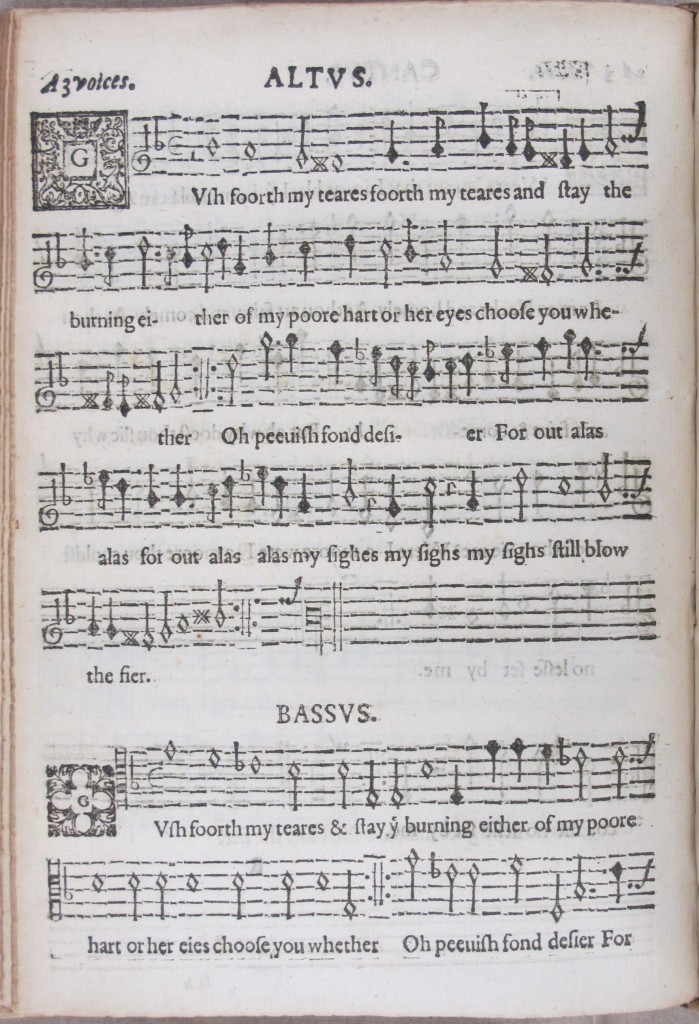

Bull is also believed to have had some connection to Cambridge, perhaps with King’s College. No University records mention him, but he appears in a minute in the journal book of the common council of the City of London (dated 23 March 1597), affiliated to King’s College. Some of his surviving music for keyboard is collected together in the so-called Fitzwilliam Virginal Book (MS Mu 168), one of the primary sources for our knowledge of Elizabethan and Jacobean music. Bequeathed to the Fitzwilliam Museum by its founder in 1816, the volume contains nearly forty pieces by Bull, alongside others by his contemporaries Giles Farnaby, Thomas Morley and the great William Byrd. Its contents have been recorded and Bull’s pieces can be found here.

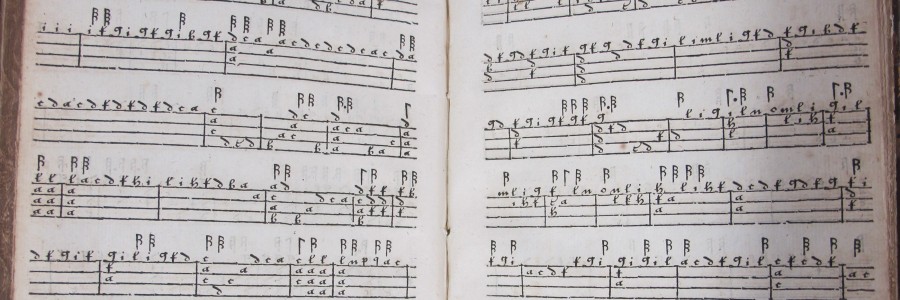

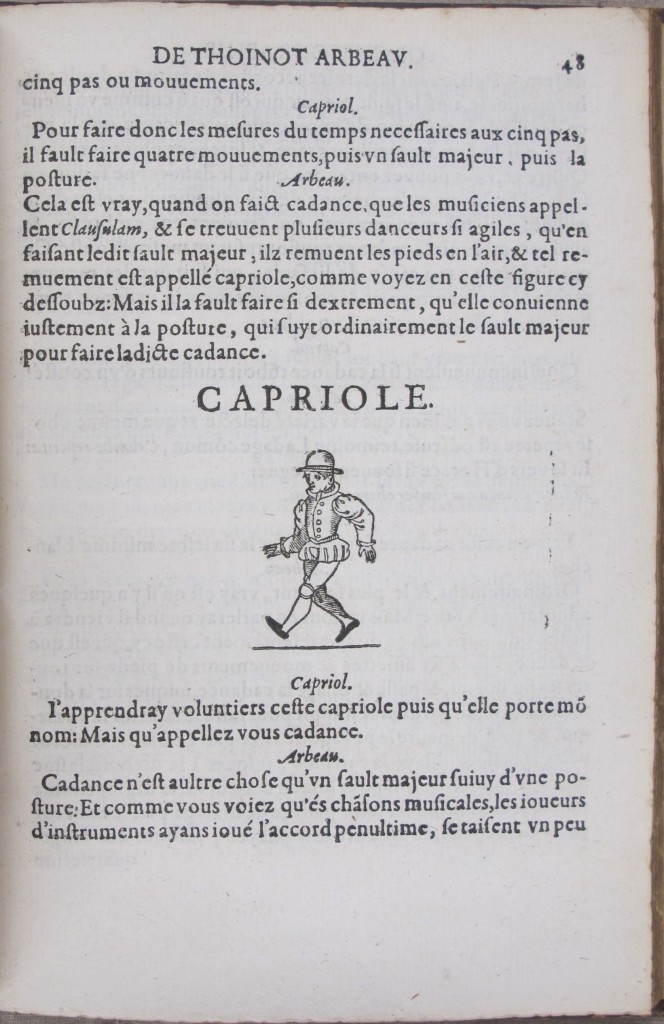

In the University Library is a volume of three musical works which once belonged to John Bull himself. It contains (1) Anthony Holborne’s The cittharn schoole (London, 1597), which contains music for the cittern (similar to a modern-day mandolin) and is one of just two copies recorded in this country; (2) Claudius Sebastianus’s Bellum musicale (Strasbourg, 1563), which recorded recent developments in polyphonic music in contrast to the more traditional use of plain chant; and (3) Jehan Tabourot’s Orchésographie (Langres, 1596), the only recorded copy of this edition in the UK. Orchésographie first appeared in 1589, printed in the French town of Langres (80km north of Dijon, Tabourot’s birthplace in 1519). It speaks of appropriate behaviour in the ballroom and on the interaction of musicians and dancers, giving a number of dance tabulations in which the steps appear alongside the musical notation. The binding containing these three works is calf, executed in London around 1600 (certainly after 1597, the date of Holborne’s work, and before 1628), and is covered in gold: the background is decorated with tiny stars, the centre of both boards is occupied by a large arabesque cartouche (the corners are similarly decorated), and the titles of the works within are given at the head of the front cover, along with the name ‘I. Bvll Dr.’ at the foot. Even the textblock has been decorated, with gauffered edges, and the spine is very heavily gilded too. According to Dr Mirjam Foot the binding is by the so-called ‘MacDurnan Gospels Binder’ (see The Henry Davis gift: a collection of bookbindings, 1978: vol. 1, pp. 38 & 47), though he died probably in the 1580s when his tools were acquired by John Bateman, a royal binder. Other elaborate bindings, evidently made for Bull, survive elsewhere, notably in the Fitzwilliam Museum, where a manuscript of Bull’s music (known as ‘The Bull Manuscript’ [Fitzwilliam MS Mu 782] and not to be confused with the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book) also carries his name on the front cover, but this time in a lengthier formula: ‘Iohn Bvll docter of mvsique organiste and gentleman of Her Ma[jest]ies moste honourable chappell’. A third volume, the so-called My Ladye Nevells Booke (BL MS Mus. 1591) – an important source of William Byrd’s music and evidently compiled in his circle in the 1590s – is in a very similar binding (though without Bull’s name), and is likely to have been bound in the same London workshop. The volume passed at some point before 1649 to Richard Holdsworth (1590-1649), Master of Emmanuel College, who left a complicated will with many clauses which might have seen his library of 10,000 volumes offered either to Emmanuel and to the University. After a long legal wrangle the books were given to the University Library in 1664, where they remain one of the most significant collections ever received. Quite how Bull came to have such beautiful books – if he commissioned them himself, or was given them as gifts – is not known, but they provide a window onto the sumptuous world of Elizabethan music-making and its connections to Cambridge.

A ‘capriole’ (meaning ‘to caper’) is a dance move, but the name is also given to a character (a student of dance) in Orchesographie, where he engages in a dialogue with the author (fol. 48)

Dear Madams, Dear Sirs,

As a former colleague of the late Christopher Hogwood, I hereby request you to inform me if the following manuscript from his collection is presently part of your library:

GB-CAMhogwood M1902,

a pair of instrumental partbooks, resp. dessus, bass, Suites by F./C. Dieupart ca. 1700.

Hoping this message reaches you, I thank you in advance for informing me about this matter.

with kind regards,

sincerely,

Bob van Asperen

Em. Prof. of Harpsichord

Conservatory of Amsterdam

Netherlands

Professor van Asperen,

Thank you for your enquiry. I have asked our Music Department about this, as I believe the material we purchased from Professor Hogwood’s library is still with them. They will be in touch with you directly.

Best wishes,

Liam Sims (Rare Books Specialist, Cambridge University Library)

My colleague tells me it is now in the British Library, and that she has replied to you directly.