‘That noble cabinet’: the British Museum and its links with Cambridge

This week is Museum Week, which seems like an excellent occasion to look at books in the University Library with connections to our national museum – The British Museum – which began life over 260 years ago. Founded in 1753 by King George II, the museum had its origins in the collections of Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753), who left them to the nation upon his death earlier that year. His natural history specimens, plants, books and manuscripts (around 71,000 objects) were soon joined by the libraries of the antiquarian Sir Robert Cotton (d. 1631) and the Earls of Oxford (known as the Harleian Library), and in 1757 George II gave what became known as the Old Royal Library. These four collections became the foundations of the Museum’s holdings, making it more a library than a museum; from its foundation until 1898 the head of the Museum was known as the ‘Principal Librarian’ and what would become known as the British Library was an integral part of the Museum until its separation in 1973. The Museum opened to the public in 1759 in what began life as a private house, known as Montagu House, built after a fire destroyed the first house on the site in 1686.

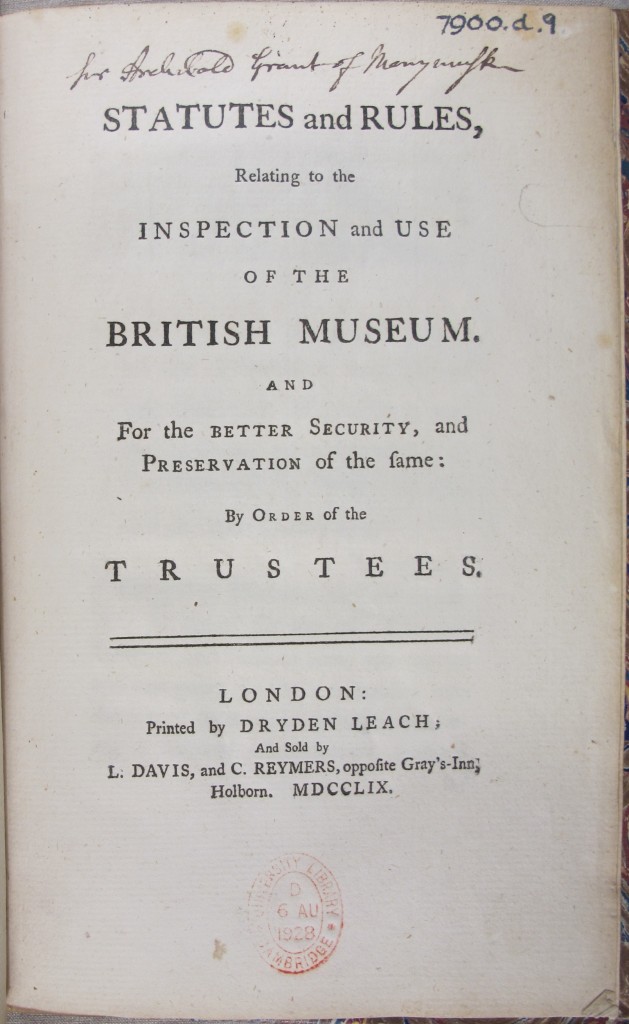

The University Library holds a number of books relating to the early history of the Museum, including the Statutes and rules relating to the inspection and use of the British Museum, printed in the year it opened to the public (1759). The work notes that the Museum was ‘designed for the use of learned and studious men, both natives and foreigners’ and that opening hours were to be 9am until 3pm Monday to Friday between September and April. During the summer months (May to August) the same hours were kept Tuesdays to Thursdays, but on Mondays and Fridays hours were 4pm until 8pm. Although the opening hours were generous, gaining admission was not quite as simple as walking up the front steps. Prospective visitors were to ‘make their application to the Porter, in writing … [with] their names, conditions, and places of abode’ and the Porter was to deliver the Register every night to the Principal Librarian – at this time the physicist Dr Gowin Knight (1713-1772) – or his representative, who would give permission (or not) for tickets to be issued.

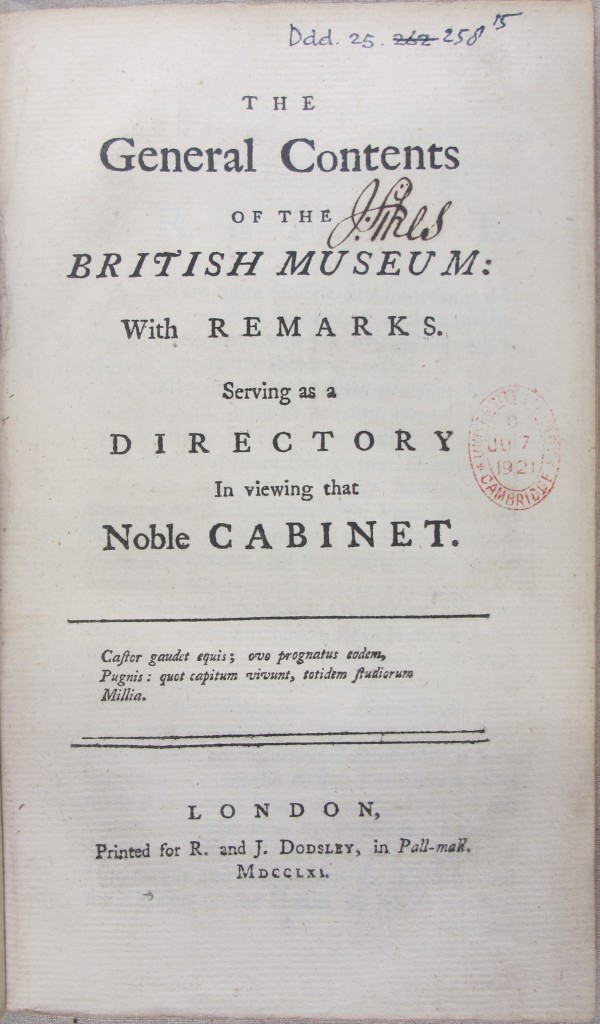

A maximum of ten visitors per hour were permitted and general wandering about the building was not allowed; instead, visitors ‘are first to be conducted through the department of Manuscripts and Medals; then the department of natural and artificial productions; and afterwards the department of printed Books, by the particular officers assigned to each department’, with an hour allowed in each. Also, rather unlike today, the rules stated that ‘no children be admitted into the Museum’. The 1761 edition of The general contents of the British Museum, with remarks serving as a directory in viewing that noble cabinet (1761) forms a sort of early visitor guidebook, listing the contents of the main collections: in the words of its author, ‘a few remarks on the general contents, without enlarging too much on any thing’. It concerns itself particularly with the great collections of books, noting that with the Museum ‘Litterature [sic] is once more recovered from its long Swoon, and now shines in its pristine Lustre’. Of the manuscripts given by George II, it is noted that there are ‘some old and curious manuscripts’ and the Cotton collection – which contained the Lindisfarne Gospels, the unique manuscript of Beowulf and one of the first exemplars of Magna Carta (1215) – which this directory calls ‘that great bulwark of our liberties’ – is said to be ‘ancient and noble’. In 1778 was published a large folio entitled Museum Britannicum: being an exhibition of a great variety of antiquities and natural curiosities, belonging to that noble and magnificent cabinet, the British Museum, which contained a number of engravings of items in the collection by the hands of Jan van Rymsdyk and his son Andreas, who worked in London from the 1760s onwards. The focus here is on objects – natural history specimens, plants, and antiquities – rather than books. Plate 26 shows two Roman pieces: a small cup above and a large gold cup decorated with oxen (from Sir William Hamilton’s collection) below.

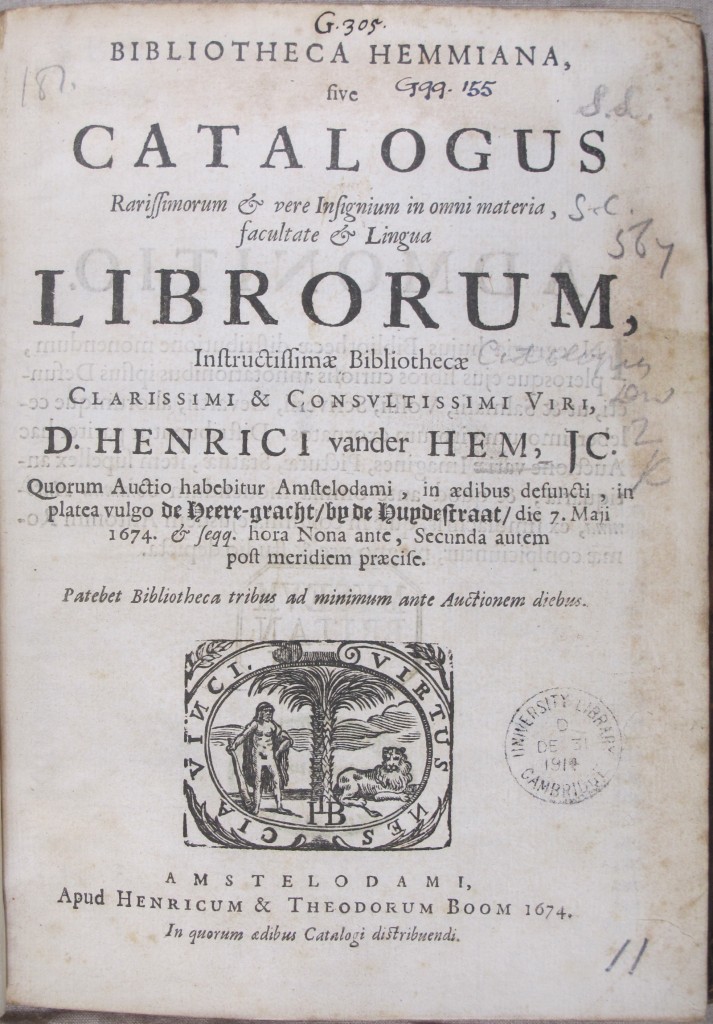

One of the primary connections between Cambridge University Library and the British Museum (Library) is the fact that many duplicates once in the latter are now in Cambridge. Between 1769 and 1832 the Museum held seven sales of duplicate books, and continued well into the twentieth century to pass such books to other UK libraries. The problem with the duplicate sales and transfers was that, because the foundation collections were not preserved as distinct collections, it was often hard to know which collection a particular book might have come from. To add to the confusion, the Museum often re-bound books, taking no care (as was common at the time) to preserve information on fly-leaves concerning the original owners. As a result, many books of impeccable provenance (including Royal books and a number from the library of Thomas Cranmer, amongst others) were ejected from the Museum, finding their way into private collections (though some would later return to the Museum, or end up in other libraries like the UL). A large number of books from Sloane’s bequest were scattered in this way, and a project is now underway to investigate the provenance of his books and to record – when it is known – which of Sloane’s books have found their ways into other public collections. One such book is a seventeenth-century sale catalogue of the library of the wonderfully named Hendrik van der Hem (d. 1674), a Dutch collector resident in Amsterdam.

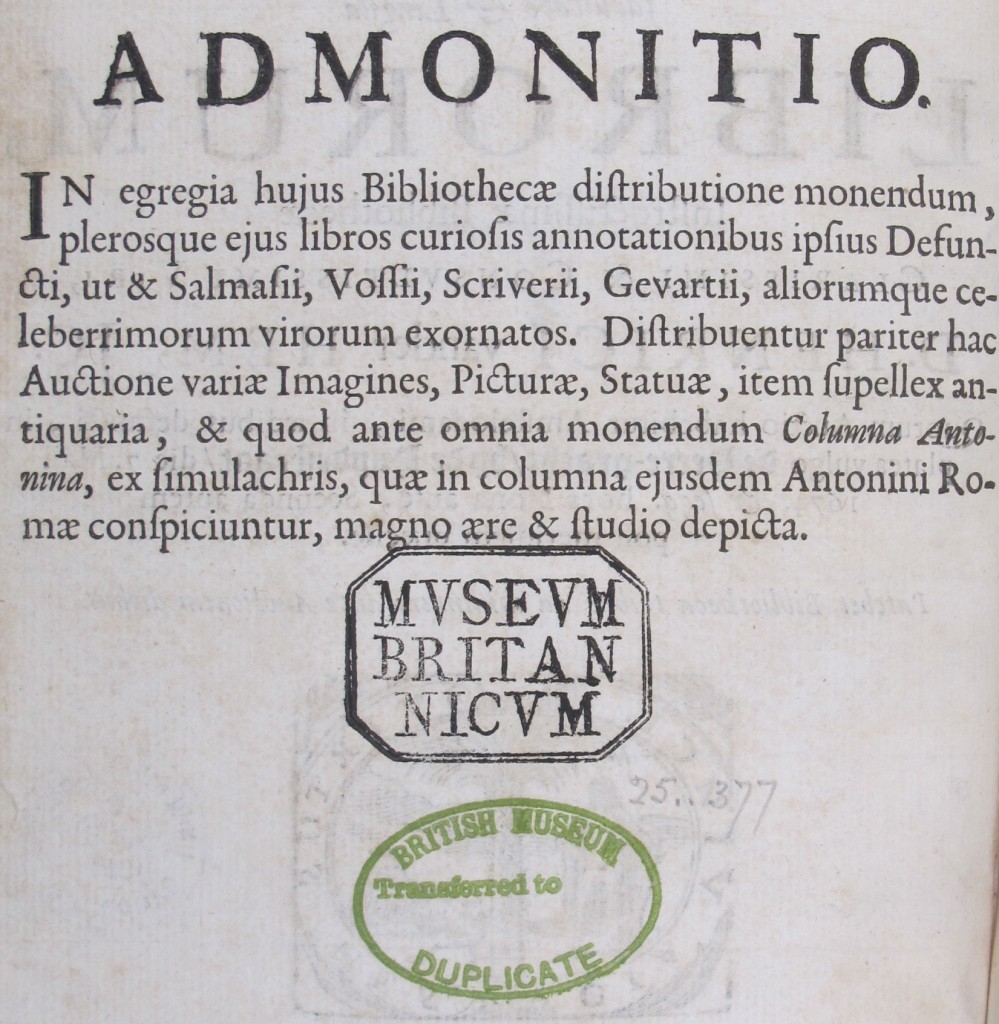

From the online Sloane catalogue, it seems likely that Sloane owned two copies of this catalogue (the one still in the British Library is also thought to have been his, and is priced), but in 1914 it was sent to the UL as a duplicate from the Museum, and now bears the shelfmark Ggg.155. The title page bears Sloane’s characteristic shelfmark, G.305, and the verso of the title page carries the original BM stamp and the duplicate stamp (see below). Sloane also owned the sale catalogue of the library of Laurens van der Hem (nephew of Hendrik), which once sat next to the 1674 catalogue on Sloane’s shelves, with the shelfmark G.304 (still in the British Library). Laurens was a great collector of maps and friend of the cartographer Joan Blaeu, owning a copy of Blaeu’s famous Atlas maior (1660-1663), handcoloured and in 46 beautifully-bound volumes. Now at the Austrian National Library in Vienna the volumes, along with the rest of Laurens’ map collection, were a tourist attraction in Amsterdam long after his death. In 1711 the German traveller Zacharias Conrad von Uffenbach (who also visited Cambridge, and met Sloane in London) visited Amsterdam, meeting Laurens’ daughter and viewing the Atlas. At least one fifteenth-century printed book now in the UL came (via the Museum) from Sloane’s library: an Italian edition of the medical works of the Arabian physician known as Pseudo-Mesue or Mesue the Younger (d. 1015 in Cairo), now at the shelfmark Inc.3.B.29.1[4277]. Pseudo-Mesue, as his name suggests, has been linked with Yuhanna ibn Masawaih (777-857), known as Mesue the Elder. This volume, printed in Modena in 1475, bears Sloane’s shelfmark (A.471) and the cancelled Museum stamp, and was sent as a duplicate by exchange in 1948.

So, there are many connections between our national Museum (and the library which grew out of it) and the University Library. Both institutions have their core collections: Sloane, Cotton, Harley and the Royal Library for the British Museum, and our own Royal Library (the books of John Moore), along with the books of Richard Holdsworth, at Cambridge, reflecting the importance of benefaction for museums and libraries alike.