Hour by Hour, Day by Day: Devotions in the Fifteenth Century

The physical dimensions of a Book of Hours give you immediate clues as to how they were used: they are small, often pocket-sized books, intended for personal use, small enough to be held easily in one’s hands at prayers or during liturgical services. As a previous blog post detailed, Cambridge University Library holds a collection of 45 Books of Hours, dating from the early 14th century to the end of the medieval period. The earliest examples known to survive are from the mid-13th century and over the course of the following two centuries varieties of Books of Hours proliferated. There remains no comprehensive conspectus of the contents, iconography, decorative styles or paratextual additions found in these manuscripts (though I have included a bibliography of some useful printed guides or studies and online resources below). As their frequent appearance in the sales catalogues of auction houses attests, Books of Hours survive in the thousands, many of them highly personalised. The task would be vast and complex – though whoever undertook it would surely earn some degree of scholarly immortality and the gratitude of manuscript cataloguers the world over. Any volunteers?

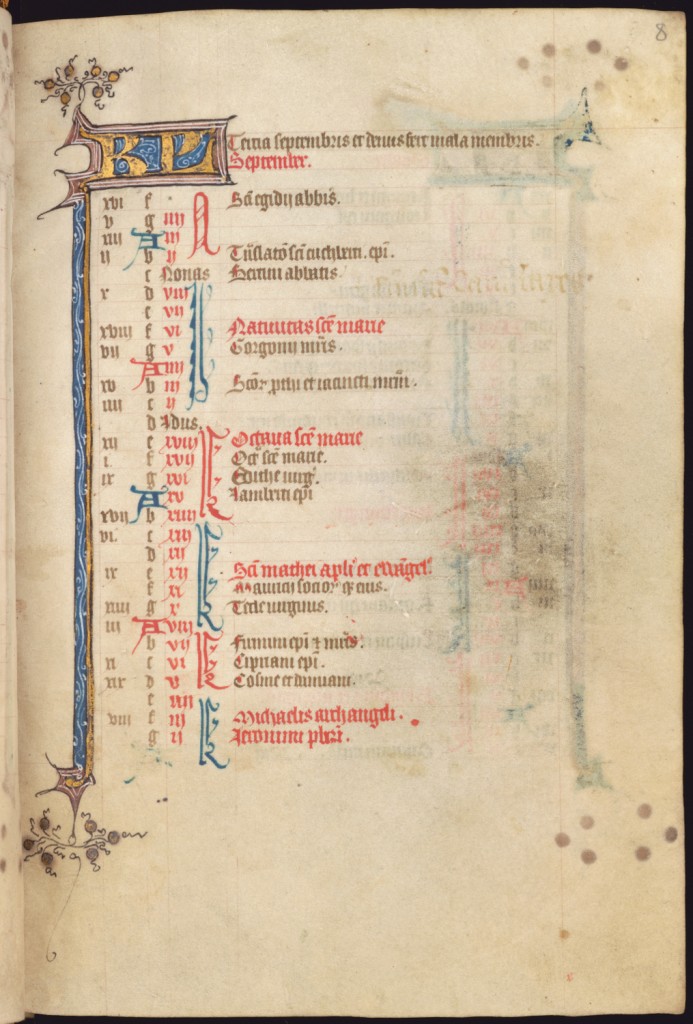

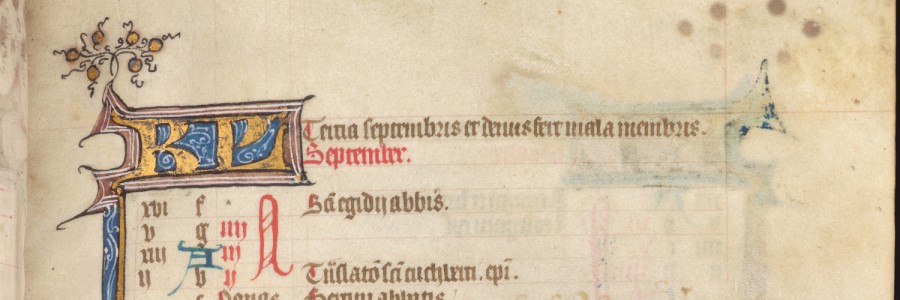

Let’s look in detail at the contents of one of the recently digitised Books of Hours: MS Ff.6.8, an early example of a Book of Hours produced in Bruges for export to the English market, made during the first quarter of the 15th century. Most commonly, Books of Hours opened with a Calendar. A page was devoted to each month. In the example shown above, the left-hand column contains the Golden Numbers used for calculating the date of the Paschal moon and thereby fixing the date of Easter and other moveable feasts; the next column contains letters that denote the day of the week; finally there are stylised letters that denote the ancient Roman system of describing days of the month based on fixed points in the future. Each begins with the ‘Kalend’ of the month, hence the decorated initials ‘KL’ at the top of the page, followed by Ides, Nones and Kalends once more. The events in the Calendar were written in coloured inks to denote the varying importance of certain feast days: major Church festivals and universal saints’ days were written in red (hence, ‘red-letter days’) or sometimes gold, while lesser feasts and saints’ days were in black or brown ink.

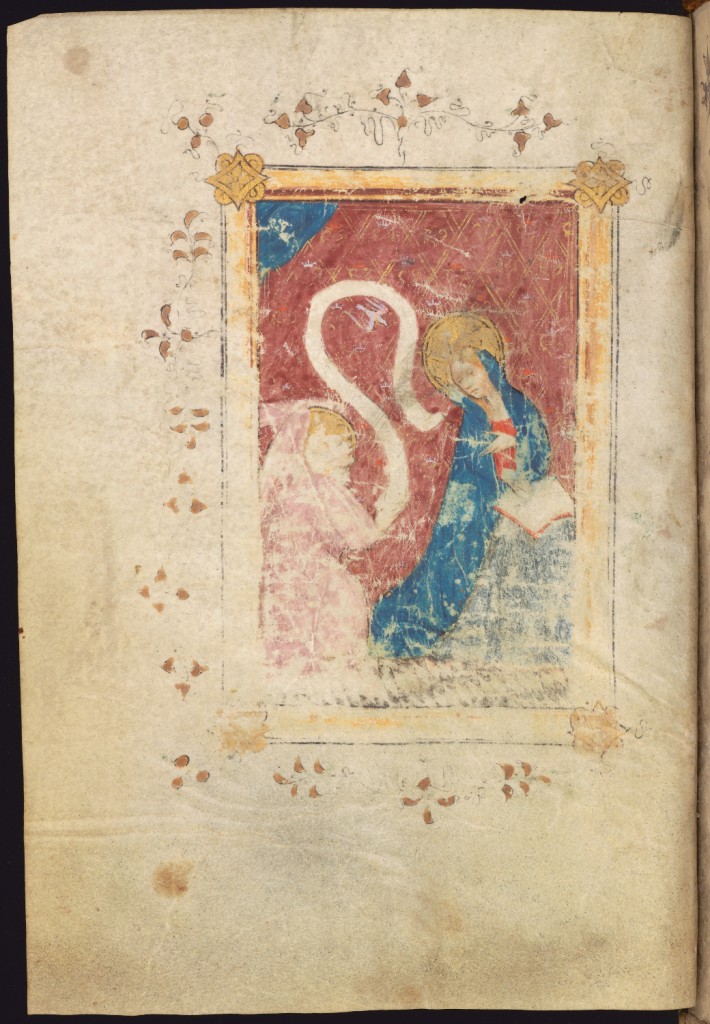

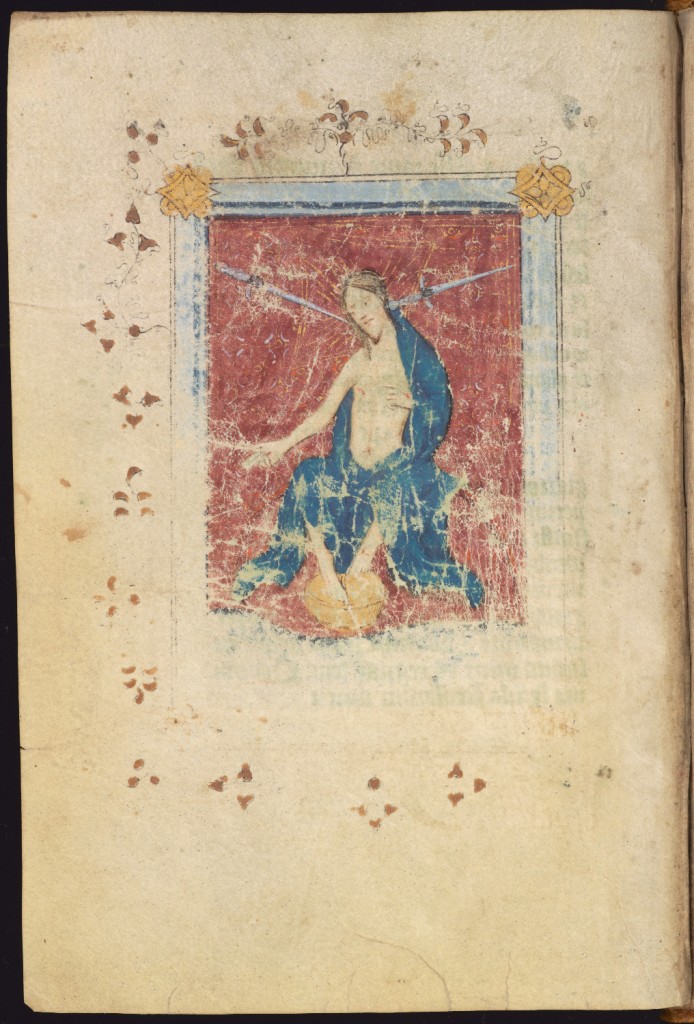

Full-page miniature of the Annunciation, before the beginning of the Hours of the Virgin, MS Ff.6.8, f. 23v

The core text of a Book of Hours was a series of devotions to the Virgin Mary, known as the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary or, more simply, the Hours of the Virgin. Comprising psalms, prayers, hymns and antiphons, they were to be performed throughout the liturgical day at the canonical hours, hence ‘Book of Hours’: these were Matins (during the night or at midnight), Lauds (dawn), Prime (mid-morning), Terce (late morning), Sext (noon), Nones (mid-afternoon), Vespers (evening) and Compline (before bed), however the exact timings in a pre-mechanised age naturally varied, not least with the changing seasons or the customs of different religious foundations.

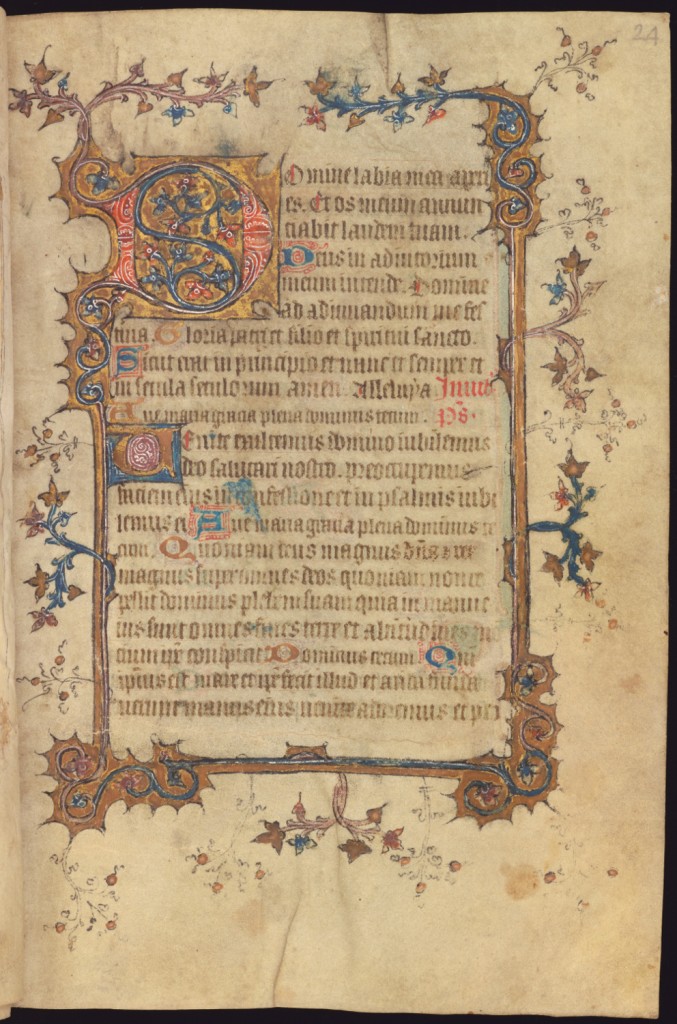

Opening of the Hours of the Virgin (Matins), with coloured initial D on gold ground, with four-sided frame of cusped burnished gold, purple and blue bars with short ivy leaf scrolls and gold studded black sprays, MS Ff.6.8, f. 24r

This programme of lay worship took its cue from that followed by the monasteries. The ‘essential’ texts were those derived from the Breviary, the liturgical book that contained the complete text of the Divine Office performed by monks and nuns (who themselves used Books of Hours for private devotional reading). The same structure was followed by the Hours of the Virgin and others found in these devotional books – the Hours of the Cross, the Holy Spirit or Holy Trinity, for example – however their overall length varied. Reflecting their liturgical derivation, they begin with a verse and response, the Gloria, antiphon, short extracts from the Psalms and hymns, interspersed with further verses, responses and prayers.

Full-page framed miniature of the Last Judgement, before the beginning of the Penitential Psalms, MS Ff.6.8, f. 98v

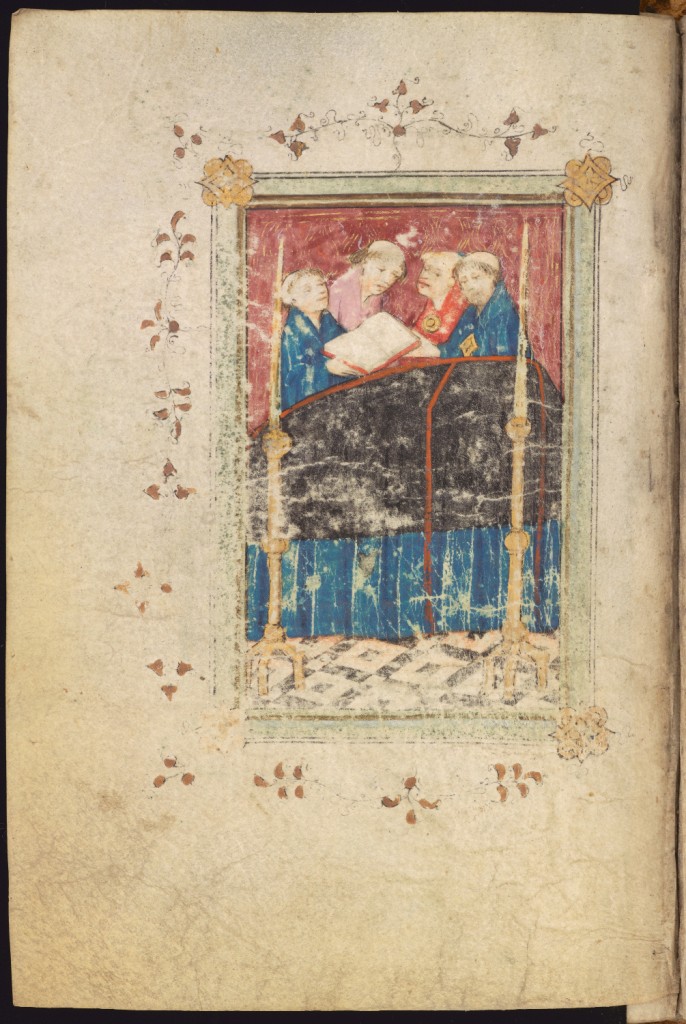

In addition to the Hours of the Virgin, these included: the Calendar, the Suffrages of the Saints (short devotions and appeals for intercession), the Penitential Psalms (expressions of grief, guilt and hope for forgiveness), the Litany (an appeal for mercy and help from the saints), the Office of the Dead (prayers to be said over a coffin at a funeral service and privately in preparation for one’s own death).

Full-page framed miniature depicting a funeral service, before the beginning of the Office of the Dead, MS Ff.6.8, f. 109v

These sections were often marked out in some way by decoration – full-page miniatures, elaborate ornamental initials, borders – that served to guide the reader through the text, provide them with images to meditate or reflect upon, and display their wealth and social status.

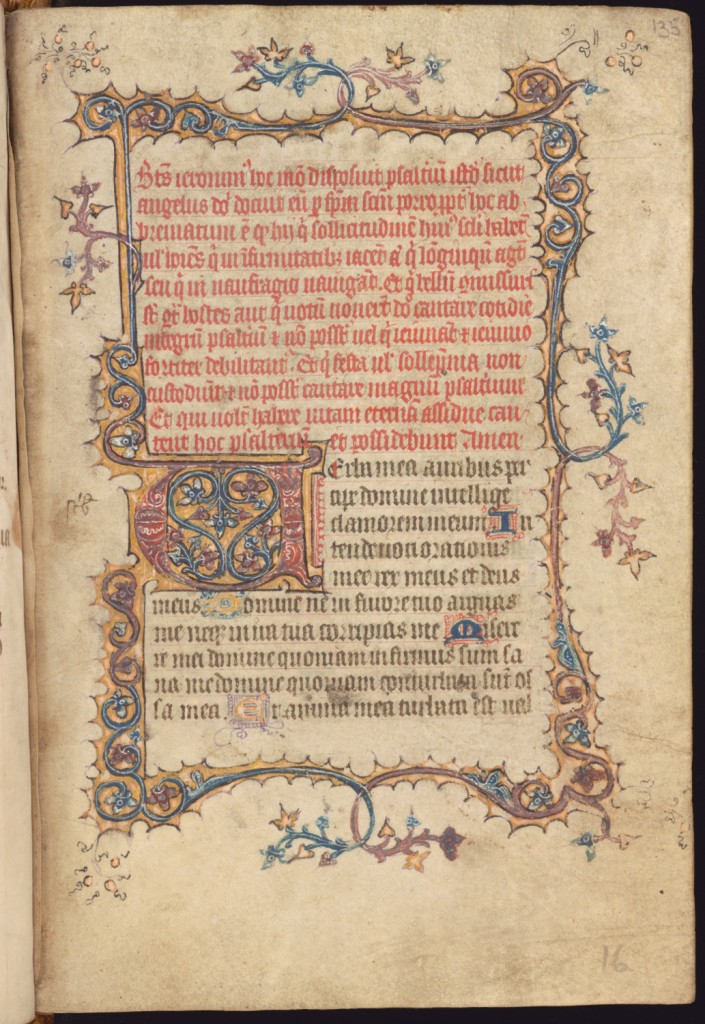

Opening of the Psalter of St Jerome, with coloured initial U on gold ground, with four-sided frame of cusped burnished gold, purple and blue bars with short ivy leaf scrolls and gold studded black sprays, MS Ff.6.8, f. 135r

Further accretions occurred over the centuries, with ‘secondary’ and ‘accessory’ texts being added to complement the essential texts and expand the devotional duties of the laity. In MS Ff.6.8, we also find the Hours of the Passion (ff. 75r-84v) and the Psalter of St Jerome (ff. 135r-142r), an anonymous collection of 183 verses from the Psalms intended for use by the sick and attributed to St Jerome.

If you visit the Cambridge Digital Library and browse through the rest of MS Ff.6.8 and through MS Ii.6.2, paying particular attention to the once blank endleaves and reverse sides of the miniatures, you will notice other additions to these manuscripts. These were made by some of the people who owned these books during the 15th and 16th centuries – several of whom can be identified by name – and they offer revealing insights into their daily lives, familial relationships and devotional concerns. A forthcoming blog post will explore these annotations and additions in further detail.

Brief list of useful introductory resources:

Erik Drigsdahl (†) and Peter Kidd, CHD Center for Håndskriftstudier i Danmark, Tutorial on Books of Hours (http://manuscripts.org.uk/chd.dk/tutor/index.html).

Eamon Duffy, Marking the Hours: English People and their Prayers, 1240-1570 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006).

Glenn Gunhouse, Hypertext Book of Hours (http://medievalist.net/hourstxt/home.htm).

John Harthan, Books of Hours and their Owners ([London]: Thames & Hudson, 1977).

Nigel Morgan and Paul Binski, ‘Private Devotion: Humility and Splendour’, in The Cambridge Illuminations: Ten Centuries of Book Production in the Medieval West, ed. by Paul Binski and Stella Panayotova (London: Harvey Miller, 2005), pp. 163-233.

University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center, Three-Part Guide to Books of Hours (http://www.hrc.utexas.edu/enews/2010/may/booksofhours.html).