The Great Fire of London

On this day 350 years ago – 2nd September 1666 – began the Great Fire of London, which burned for three days, consuming 13,000 houses, 87 churches and the city’s great medieval cathedral. Fires were a common occurrence in early modern London – at the time largely made up of timber-framed buildings – and a number of observers were clearly unconcerned in its early stages. The Lord Mayor of London, Thomas Bloodworth (who proved fairly useless at overseeing the efforts to quench the conflagration) was said to have remarked on the night of 2nd September that ‘a woman might piss it out’, and the naval administrator Samuel Pepys was awoken by his maid at 3am on 2nd September, noting ‘I thought it far enough off and so went to bed again and to sleep’. The University Library holds a number of books from the period which tell us about the fire, and Pepys’ diary has long been kept in Cambridge, at Magdalene College with his fine library. Along with the record of John Evelyn, Pepys’ words gives us a detailed and personal account of the fire and its aftermath, at times bringing the reader right into the action; after recording the destruction of the church of St Magnus the Martyr that morning (very close to Pudding Lane, where the fire took hold) Pepys noted that:

…poor people [stayed] in their houses as long as till the very fire touched them, and then [ran] into boats … among other things, the poor pigeons, I perceive, were loth to leave their houses, but hovered about the windows and balconys till they were, some of them burned, their wings, and fell down

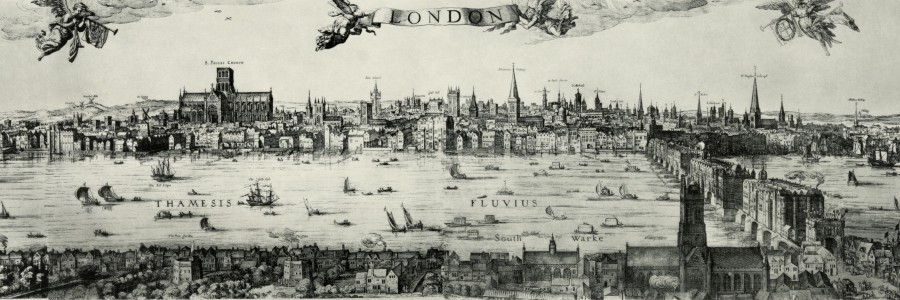

The fire from the south, in Samuel Rolle’s “The burning of London in the year 1666” (London, 1667), shelfmark 8.38.18[1]. St Paul’s can be seen on the left and St Mary Overie (later Southwark Cathedral) in the foreground, with the river Thames filled with terrified people fleeing with their possessions. On the south side of London Bridge can be seen pikes displaying the heads of executed traitors

Later on Pepys travelled to Whitehall where he was the first to impart news of the fire to King Charles II, who ordered the Lord Mayor to pull down houses around the fire to prevent its spread. By the evening of 2nd Pepys recorded the movement of the fire to the west, from his viewpoint on Bankside: ‘[I] saw the fire grow; and, as it grew darker, appeared more and more, and in corners and upon steeples, and between churches and houses, as far as we could see up the hill of the City, in a most horrid malicious bloody flame, not like the fine flame of an ordinary fire’. On 4th comes one of the most famous parts of Pepys’ record – the safe burial of his cheese:

Sir W. Batten not knowing how to remove his wine, did dig a pit in the garden, and laid it in there; and I took the opportunity of laying all the papers of my office that I could not otherwise dispose of. And in the evening Sir W. Pen and I did dig another, and put our wine in it; and I my Parmazan cheese, as well as my wine and some other things.

Wenceslaus Hollar’s image of St Paul’s aflame, from the title page of William Sancroft’s “Lex ignea: or, the School of righteousness” (London, 1666), shelfmark Hhh.943[1]. Notice the classical additions by Inigo Jones, in the centre, the loss of which was lamented by Evelyn

The destruction of St Paul’s, a great symbol of London, was particularly sad. On 4th September John Evelyn, another great book collector, recorded that ‘the stones of Paules flew like granados [grenades], the Lead mealting down the streetes in a streame, & the very pavements of them glowing with a fiery rednesse, so as nor horse nor man was able to tread on them’ and on 7th recorded the full magnitude of its destruction, worth quoting at length:

I was infinitly concern’d to find that goodly Church St. Paules now a sad ruine, & that beautifull Portico (for structure comparable to any in Europ, as not long before repaird by the late King) now rent in pieces, flakes of vast Stone Split in sunder … It was astonishing to see what imense stones the heate had in a manner Calcin’d, so as all the ornaments, Columns, freezes, Capitels & projectures of massie Portland stone flew off, even to the very roofe, where a Sheete of Leade covering no lesse than 6 akers by measure, being totaly mealted, the ruines of the Vaulted roofe, falling brake into St. Faithes, which being filled with the magazines of bookes, belonging to the Stationers, & carried thither for safty, they were all consumed burning for a weeke following … Thus lay in ashes that most venerable Church, one of the antientest Pieces of early Piety in the Christian world.

The loss of the cathedral was all the more awful for the city’s booksellers, whose trade had long been clustered around its churchyard. The Stationers’ Company (the ancient livery company which controlled printing in the city) removed its stock of books to the vaults for safety, as did many booksellers, never thinking that the building would go up in flames too. Pepys records the losses of the booksellers on 26th September:

I hear the great loss of books in St Paul’s Church-yarde, and at their Hall [the Stationers’] also, which they value about £150,000; some booksellers being wholly undone, among others, they say, my poor Kirton. And Mr Crumlu [Samuel Cromleholme] all his books and household stuff burned; they trusting St Fayth’s [the chapel underneath the main floor of the cathedral], and the roof of the church falling, broke the arch down into the lower church, and so all the goods burned. A very great loss.

Such wholesale destruction of the booksellers’ stock caused prices to rocket. In April 1667 Pepys’ new bookseller, Starkey, persuaded him that the rarity of a book worth 8 shillings pre-fire (Rycaut’s The present state of the Ottoman Empire, dated 1667 but published in the year of the fire) was a good enough reason to pay 55 shillings for it now (nearly £3), there being only a couple of dozen copies left. Pepys was clearly taken in and agreed to the sale, being pleased that he had acquired the last available copy of six with fine hand-colouring (the others having been snapped up by the King and the Duke of York, among others). Only five copies are recorded in institutional hands today (though surprisingly it is not in the British Library), of which one is in the University Library, among the books of James Yorke, Bishop of Ely (d. 1808).

In the aftermath of the fire it was decided to use the opportunity to create an elegant new city from the ruins, comparable to Paris or Rome in the grandeur of its sweeping boulevards. Plans were submitted by a number of eminent men of the day, including Robert Hooke, Christopher Wren and John Evelyn himself, but these came to nothing after it became clear that working out who owned which bits of land and how much they ought to be paid for them was going to be an impossible job. Nonetheless, the new city – built on the old street plan – had wider streets and houses of brick and stone, which made it much safer when it came to the spread of fire. Its new cathedral, designed in the baroque style by Christopher Wren, was a fitting monument to the city’s regrowth.

A number of public events are taking place to mark this anniversary. Exhibitions have been put together at the Museum of London (Fire! Fire!) and the Royal College of Physicians (‘To fetch out the fire’: reviving London, 1666), whose buildings in the city were destroyed in 1666, with the loss of part of the College’s library. A number of events are taking place at St Paul’s itself and on 4th September a vast wooden replica of the city, 120 metres long and moored on the Thames, will be set alight.

![The shell of St Paul's, with Inigo Jones' portico, drawn by Thomas Wyck c.1673 [public domain]](https://specialcollections-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Wyck-St-Pauls.png)

Great info.!

Thank you for pointing out the effects on the booksellers. We really don’t know all of what was lost, do we.

Indeed. One collector lost his entire library and Pepys recorded that he died soon after, people said of a broken heart. And there’s a book at Emmanuel College (http://www.emma.cam.ac.uk/library/special/highlights/?) – a c.1520 Book of Hours – which was found under the Dean’s stall in the burned-out cathedral.