Capability Brown at 300

A guest post by Katy Layton-Jones, School of Historical Studies, University of Leicester

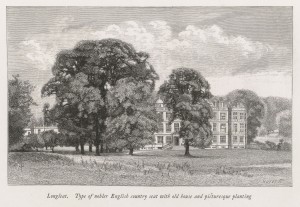

Baptised three hundred years ago, Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown (1716–1783) remains one of the most influential figures in British garden history. Brown’s vision was to have a dramatic effect, not only on the particular estates he shaped, but upon the perception and reception of British topography in general. His work can be seen in some of the finest country estates and his principles of comfort and elegance were to influence landscapes as diverse as suburban gardens and municipal public parks. Capability Brown: landscapes in line and ink, a new online exhibition by Dr Katy Layton-Jones of Leicester University, largely based on printed sources from Cambridge University Library’s collections, is now available via the U.L.’s Virtual Exhibitions webpage. The exhibition features views of some of Brown’s best-known landscapes, including Longleat, Chatsworth, Blenheim, Stowe and Audley End.

Wealthy landowners recently returned from the Grand Tour of Europe sought to replicate the classical landscapes they had seen idealised in paint. Although only a tiny minority had both the estate and the money necessary to realise his schemes, improvements to road infrastructure meant that a growing number of middle-class travellers could inspect Brown’s work in the capacity of ‘polite tourists’. By the end of the century, the expanding publishing industry was serving the largest audience of Brown’s landscapes – the armchair traveller. While verbal accounts were helpful, most popular by far were illustrated volumes. A legion of artists served this market, travelling and recording Brown’s landscapes in pencil, oil, watercolour and ink. The result is a rich record of Brown’s landscapes as they were viewed by his contemporaries and by successive generations.

Some of the earliest accounts of Brown landscapes are to be found in gazetteers, county histories and annals of individual families. This genre of literature was well established by the time Brown and his peers began their radical transformation of country estates. Nonetheless, the rapid expansion of the publishing industry, along with a growing fascination for British antiquities and topography, produced an increasingly diverse market for such accounts. The popularity of such histories endured long after many of the estates for which Brown worked had been redeveloped or sold, and continues in the guidebooks produced by organisations such as the National Trust and English Heritage.

Highbrow histories and antiquarian studies were slowly succeeded by publications for modern travellers, in the form of picturesque tours, handbooks, road books, and eventually, railway guides. For those still unable or unwilling to travel, an increasing number of elaborate engravings reproduced the sights encountered for vicarious consumption, often alongside an author’s personal appraisal of their aesthetic appeal. Within such a format, Brown’s landscapes reached new readers, but also came under renewed scrutiny.

The close relationship between landscape architecture and landscape painting ensured that Brown’s work attracted the attention of artists as well as tourists and publishers. While many derivative views were produced by professionals and amateurs alike, the beauty of improved estate gardens and parks led many of the most influential and innovative artists to paint them, either speculatively or under commission. This was perhaps unsurprising as the landscapes themselves had so frequently been inspired by art. Brown and his fellow architects fuelled a cycle of influence between art and reality that reshaped the nation’s approach to both the natural and the man-made world.

As literacy levels increased across Britain, so too did the potential market for accounts of Brown’s landscapes. New publishing genres evolved that exploited technological innovations, such as steel engraving (1824), steam presses (1830s), and Knight’s colour printing process (1838). Expensive multi-volume works continued to be published, but alongside them popular magazines, slim pamphlets and paper-bound guidebooks proliferated. As formats changed so too did the tone and many descriptions became more journalistic and sometimes critical in their approach. Beyond the publishing world, views of country houses and parks found their way onto entirely new consumer products, including mass-produced souvenirs. This explosion in image production and circulation ensured that Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown became, and remains, one of the most famous and influential names in British landscape architecture.

Pingback: Capability brown at 300 _ cambridge university library special collections brown university departments