Reading Between the Lines: An 11th-Century Bilingual Psalter

The sixth of our ‘Treasures of the University Library’ talks was given by Dr James Freeman, Medieval Manuscripts Specialist:

A psalter is a book that contains the Psalms; a bilingual psalter is simply one in which the text or parts of it have been translated into another language. Cambridge University Library possesses an unusual and intriguing example of such a psalter, MS Ff.1.23, in Old English and Latin. It was made on the cusp of the Norman Conquest, which not only supplanted the Anglo-Saxon ruling class, but also the native language of this country. Bilingual psalters were being produced throughout the period between the 8th and 15th centuries; there are even examples of trilingual psalters (I have yet to come across a quadrilingual psalter, but please write in if you know of one). The earliest examples contain interlinear glosses – notes between the lines of text, often in smaller handwriting and/or a different script to distinguish them – which rendered selected words into the vernacular. The Vespasian Psalter at the British Library (Cotton MS Vespasian A I) contains such a gloss, in Old English, which has the distinction of being the oldest extant translation into English of any biblical text.

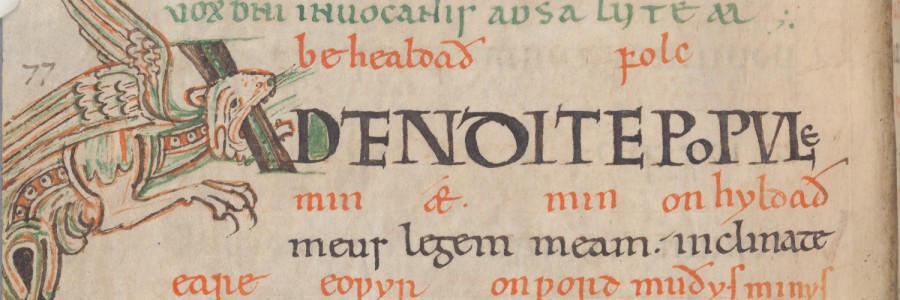

Beginning of Psalm 1 (‘Beatus uir’), in Old English and Latin on alternate lines, with a large initial B tinted in brown and tan, comprising shafts ending in zoomorphic interlaces and bows enclosing looped acanthus leaves and linked by a mask-head, framed by acanthus foliage bars; England, 2nd quarter of the 11th century, MS Ff.1.23, f. 5r

Beginning of Psalm 1 (‘Beatus uir’), in Old English and Latin on alternate lines, with a large initial B tinted in brown and tan, comprising shafts ending in zoomorphic interlaces and bows enclosing looped acanthus leaves and linked by a mask-head, framed by acanthus foliage bars; England, 2nd quarter of the 11th century, MS Ff.1.23, f. 5r

Where the whole text of the Psalms has been translated, the two versions are commonly placed alongside one another in parallel vertical columns or on alternate lines. It is the latter arrangement that is found in MS Ff.1.23. Though not quite as ancient as the Vespasian Psalter, our manuscript bears some relation to it (as we shall see below) and illustrates how the presentation of this genre of manuscript was developing. Moreover, MS Ff.1.23 is an important witness to the complex and vibrant insular religious and linguistic culture of Anglo-Saxon England.

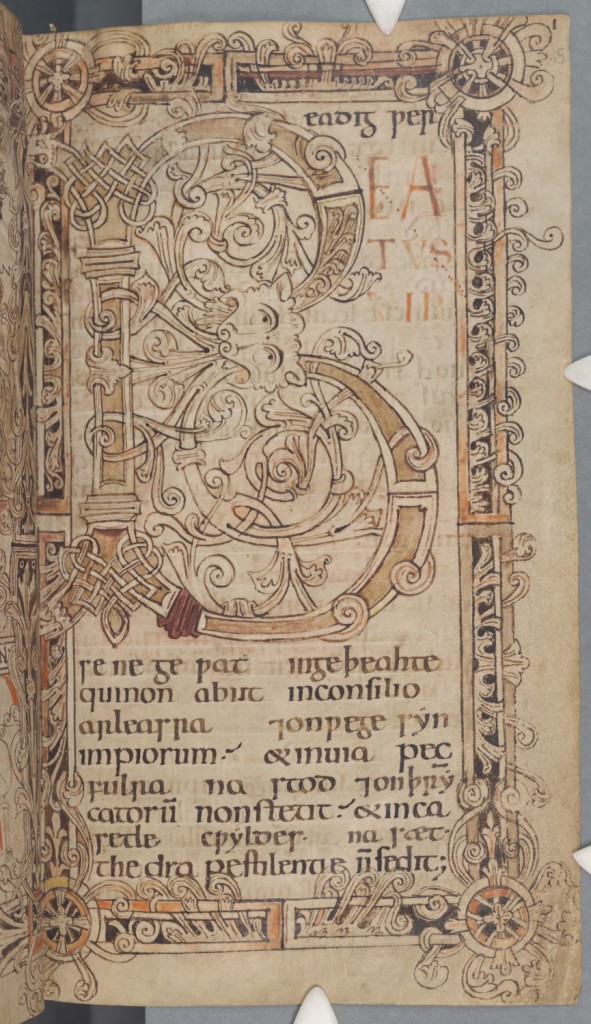

Litany of the saints, with St Kenelm’s name located on the penultimate line of the left-hand column, and picked out in tinted majuscule script, and St Budoc’s name in the lower part of the right-hand column; MS Ff.1.23, f. 274v

Litany of the saints, with St Kenelm’s name located on the penultimate line of the left-hand column, and picked out in tinted majuscule script, and St Budoc’s name in the lower part of the right-hand column; MS Ff.1.23, f. 274v

The core part of this manuscript – the text of the Psalms, followed by the canticles, litany of saints and prayers – was copied in the second quarter of the 11th century, apparently by a single scribe. He was almost certainly a monk, an Englishman, and therefore one of the last generation of native speakers of Old English – but where was he working? Scholars remain divided on this question: the manuscript offers conflicting clues that have yet to be satisfactorily resolved. In the litany of saints, the scribe picked out the name of St Kenelm in a majuscule script (essentially a medieval version of capital letters), with each letter tinted with dots of red pigment. Evidence of this Anglo-Saxon saint’s importance to the scribe or the community in which he lived, this suggests that the manuscript emanated from St Kenelm’s burial place, Winchcombe Abbey in Gloucestershire.

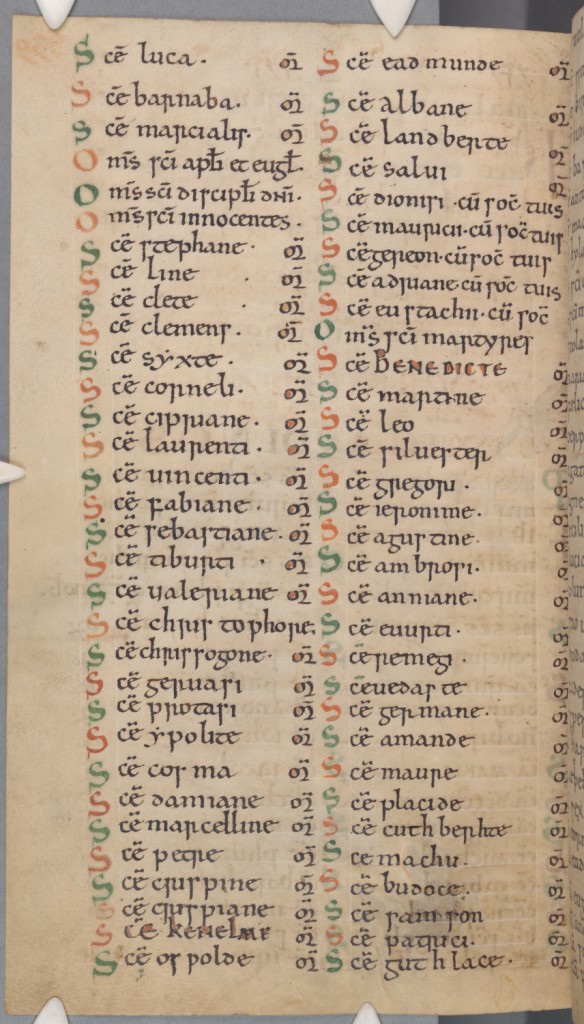

Litany of the saints, with the names of East Anglian saints in the lower part of the left-hand column; MS Ff.1.23, f. 275r

Litany of the saints, with the names of East Anglian saints in the lower part of the left-hand column; MS Ff.1.23, f. 275r

However, other names listed in the litany point in a different direction: Sts Æthelthryth, Sexburg and Eormenhild, all of whom were East Anglian saints. Just across the page from their names is that of the Breton St Budoc, known only in one other English manuscript: the Metrical Calendar of Ramsey Abbey (now Oxford, St John’s College, MS 17), copied around 1110-11 but derived from an exemplar made in the late 10th century. Another rare saint included in MS Ff.1.23, Wenburg, is likewise found in a single other manuscript, another psalter made for use at Ramsey (British Library, Harley MS 2904). In that manuscript (and others from Ramsey), St Kenelm is similarly commemorated.

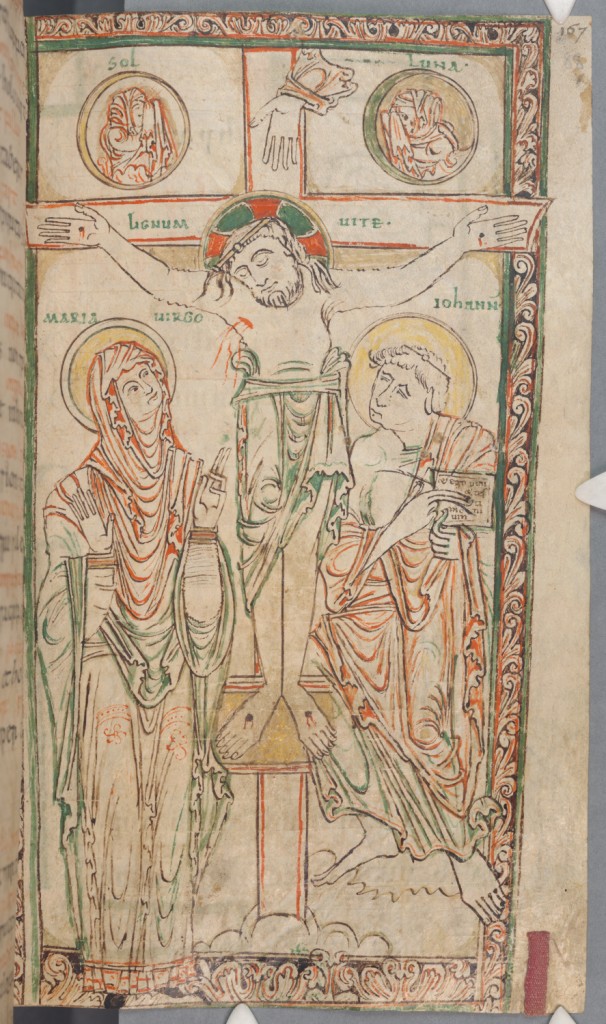

Full-page miniature of the Crucifixion, in ink and tinted with brown, orange, green and yellow, framed by acanthus foliage bars; MS Ff.1.23, f. 88r

Full-page miniature of the Crucifixion, in ink and tinted with brown, orange, green and yellow, framed by acanthus foliage bars; MS Ff.1.23, f. 88r

There is also the question of the artwork in the manuscript: specifically, a series of four full-page miniatures, executed in pen and tinted with muted earth tones. Of particular relevance here is the miniature of the Crucifixion. Around Christ on the Cross are depicted, above, weeping personifications of Sol and Luna, with the hand of God blessing Christ; to the left, the Virgin Mary; to the right, St John, writing on a tablet ‘Et ego vidi et testimonium’ (‘And I saw and bore witness (that this is the Son of God)’, John 1:34). This miniature is comparable to the near-contemporary example found in the ‘Ramsey Psalter’ (Harley MS 2904) mentioned above. Might MS Ff.1.23 have come not from western but eastern England, not from Winchcombe but Ramsey Abbey?

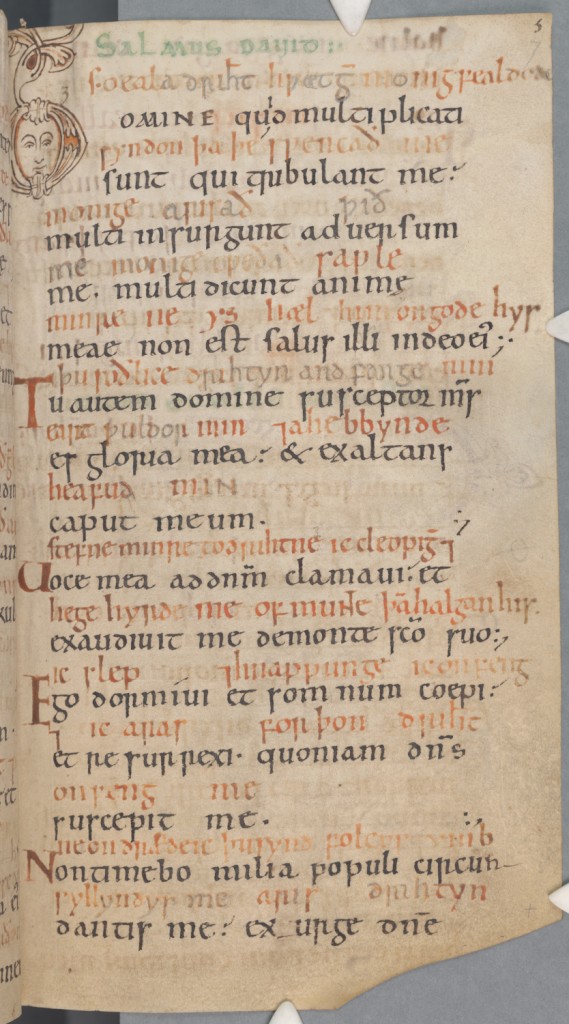

Beginning of Psalm 3 (‘Domine quid multiplicati’), with foliate initial D enclosing a human face, and Latin title written in green ink above, with alternate lines of Old English and Latin written in insular minuscule script in red and brownish-black ink; MS Ff.1.23, f. 7r

Beginning of Psalm 3 (‘Domine quid multiplicati’), with foliate initial D enclosing a human face, and Latin title written in green ink above, with alternate lines of Old English and Latin written in insular minuscule script in red and brownish-black ink; MS Ff.1.23, f. 7r

Let us put the question of this manuscript’s provenance to one side for a moment, in order to take a closer look at its contents. MS Ff.1.23 contains the complete text of the Psalms in both Latin and Old English. It is unique among the nine surviving Old English/Latin Psalters, because the handwriting used for both is of the same scale. The scribe distinguished the two from one another in other ways: by type of script and ink. He began by copying the Latin text in a continental style of handwriting, Caroline minuscule; the Old English, meanwhile, he wrote out in a variant of that script used in England, insular minuscule. As his large and rather clumsy handwriting indicates, our scribe lacked the finer skills of penmanship; indeed, after the first three pages, he abandoned the continental script entirely, thereafter copying both the Latin and Old English in the presumably more familiar and comfortable insular version.

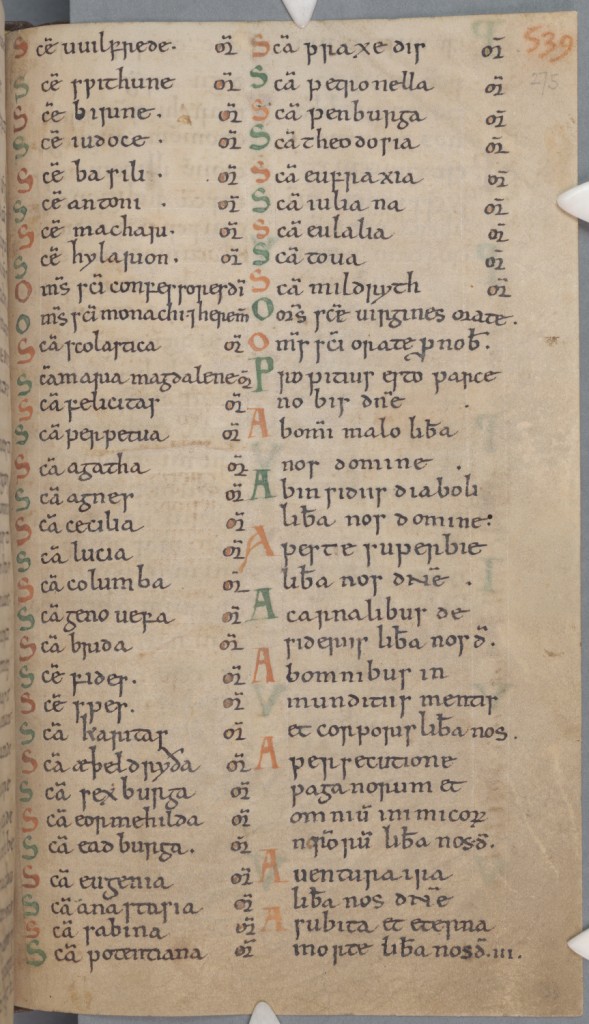

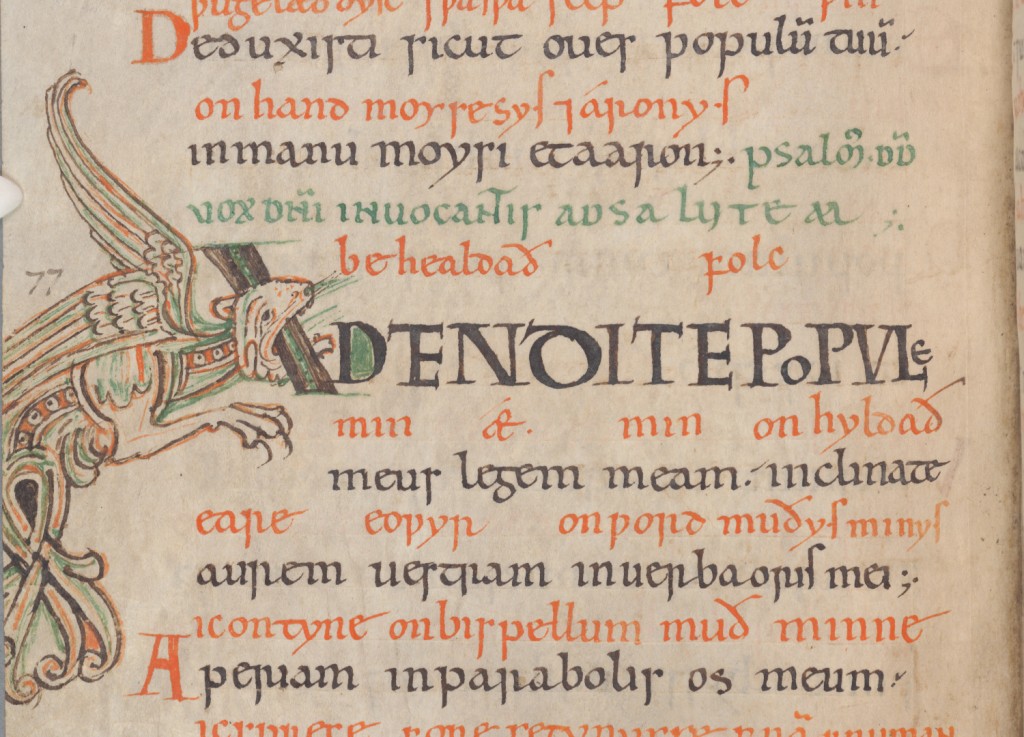

Beginning of Psalm 78 (‘Adtendite popule’), with zoomorphic initial A with biting dragon hybrid; MS Ff.1.23, f. 131v (detail)

Beginning of Psalm 78 (‘Adtendite popule’), with zoomorphic initial A with biting dragon hybrid; MS Ff.1.23, f. 131v (detail)

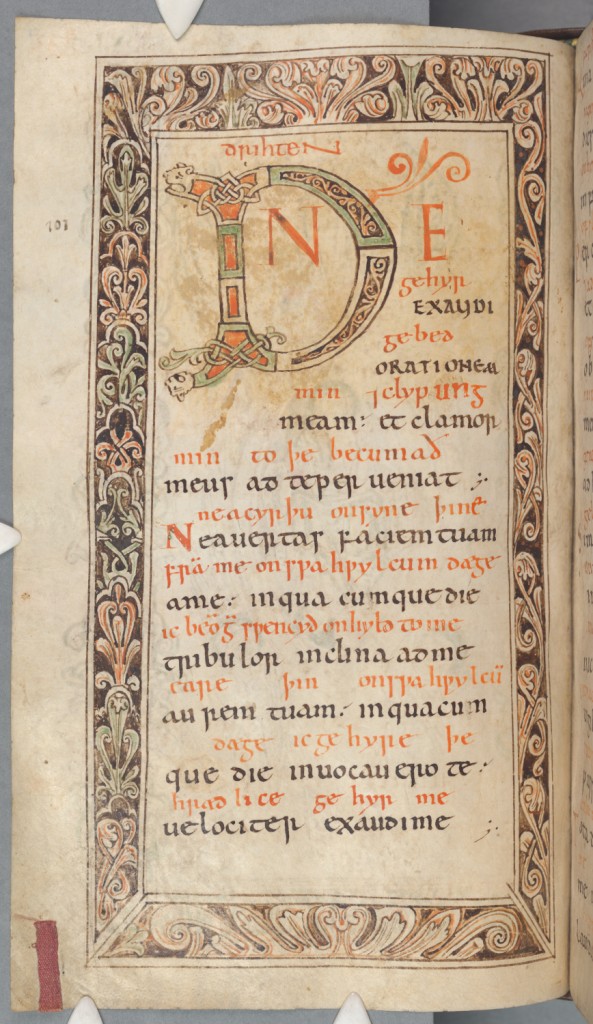

The scribe was more consistent in his use of different inks: throughout the manuscript, he copied the Latin text in a brownish-black ink and the Old English in red ink. Though now faded in many places, often to a somewhat watery orange, the Old English text would originally have sprung off the page. Red ink was commonly used in medieval manuscripts for headings or titles or to denote passages of text of particular importance. It is from the Latin word for red, ruber, that the terms for this practice and for the text so written – ‘rubrication’ and ‘rubrics’ – ultimately derive. In MS Ff.1.23, bright red lines of Old English precede rather dull brownish-black lines of Latin on every page. The visual effect is one in which the vernacular text of the Psalms possesses a more imposing presence on the page than the Latin text.

Beginning of Psalm 101 (‘Domine exaudi orationem meam’), with large initial D tinted in brown, green and orange with zoomorphic interlaces, framed by acanthus foliage bars; MS Ff.1.23, f. 171v

Beginning of Psalm 101 (‘Domine exaudi orationem meam’), with large initial D tinted in brown, green and orange with zoomorphic interlaces, framed by acanthus foliage bars; MS Ff.1.23, f. 171v

There is textual evidence, compelling and complementary to the visual details, to support the contention that the Old English Psalms possessed an at least equal importance to the Latin in this manuscript. Numerous errors of transmission in the Latin text shows that our scribe did not know the language well. Mirroring his comfort with insular handwriting is his familiarity with the vernacular rendering of the Psalms. The Old English text could, and probably did, stand alone as a translation: the reasonably consistent spelling of the words reflects a stable pronunciation of this text, which one would expect from a native speaker at ease with reading or reciting this version.

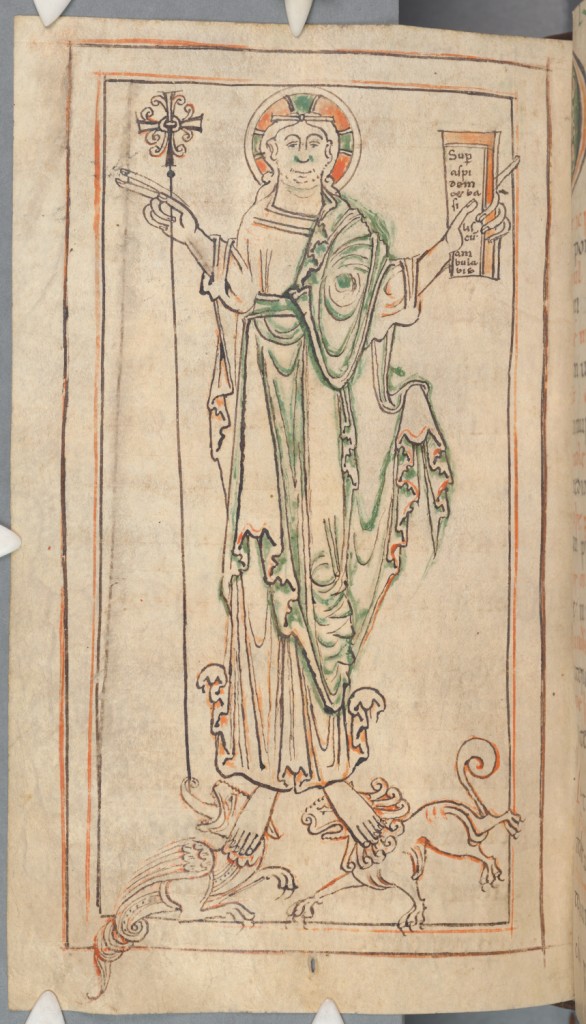

Full-page miniature of Christ trampling on a lion and a basilisk, holding a tablet inscribed ‘Super aspidem et basiliscum ambulabis’ (‘Thou shalt trample the lion and the basilisk’; Psalm 91); MS Ff.1.23, f. 195v

Full-page miniature of Christ trampling on a lion and a basilisk, holding a tablet inscribed ‘Super aspidem et basiliscum ambulabis’ (‘Thou shalt trample the lion and the basilisk’; Psalm 91); MS Ff.1.23, f. 195v

From where might this Old English text have originated? Another possible provenance for this manuscript now arises. The Old English in MS Ff.1.23 is closely dependent upon that found in the Vespasian Psalter. While its earlier whereabouts are not completely clear, the Vespasian Psalter was demonstrably in Canterbury around the same time that MS Ff.1.23 was being made: Eadwig Basan (fl. c. 1020), monk of Christ Church Cathedral Priory, added several texts to the Vespasian Psalter. We cannot prove that MS Ff.1.23 was copied directly from the Vespasian Psalter, however palaeographical evidence has also been adduced by scholars in support of a Canterbury provenance for MS Ff.1.23.

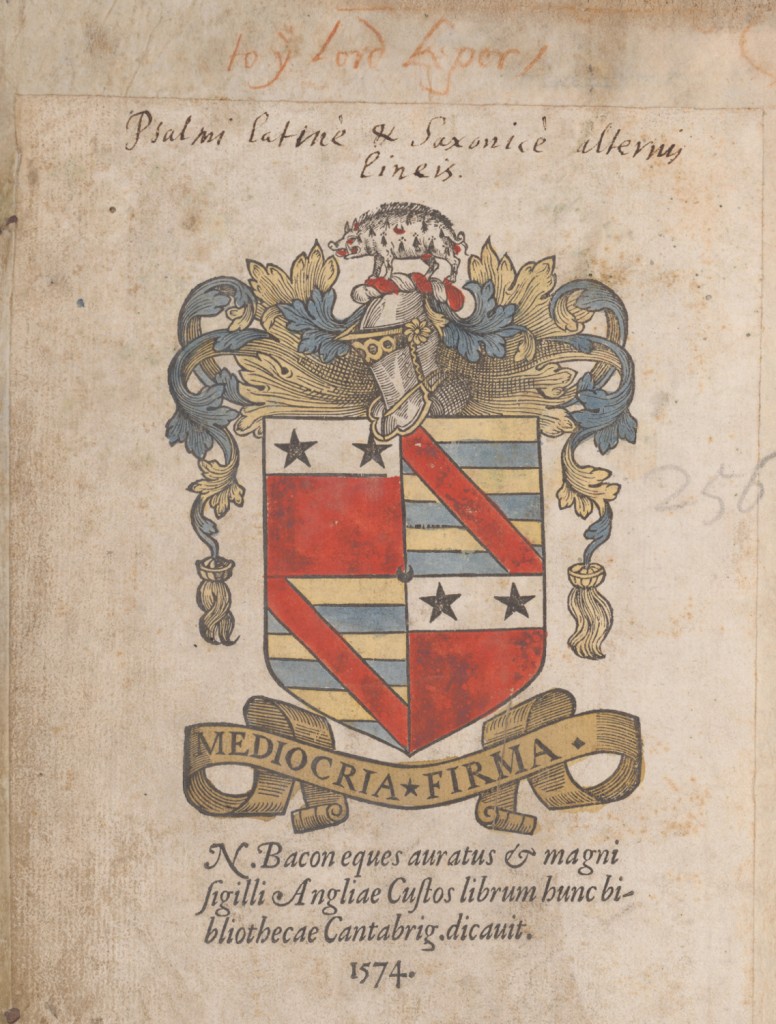

An inscription in orange crayon by Matthew Parker and the dedication bookplate of Nicholas Bacon; MS Ff.1.23, front pastedown (detail)

An inscription in orange crayon by Matthew Parker and the dedication bookplate of Nicholas Bacon; MS Ff.1.23, front pastedown (detail)

Wherever this manuscript was originally made and owned, it has spent close to half of its life in the custodianship of the University Library of Cambridge. Turning to the front of the manuscript, we find evidence of how it arrived here. Like the Vespasian Psalter, this manuscript passed through the hands of Matthew Parker, Archbishop of Canterbury under Elizabeth I. Parker is now perhaps most famous as the benefactor of his eponymous library at Corpus Christi College, where his personal collection of some 600 or so immensely precious medieval manuscripts have been housed since his death. The University Library also benefited from Parker’s munificence, receiving both manuscripts and printed books from him. His friends and colleagues likewise were given books: an inscription on the front pastedown reads ‘to the lord keper’, meaning Sir Nicholas Bacon, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal. The dedication bookplate below is the earliest English example of its kind. It contains Bacon’s coat of arms, motto and a record of his gift of the book in 1574 to the University Library, where it has remained ever since.

Would you like to see more of MS Ff.1.23? The manuscript has been digitised in full and the images and a detailed description of the manuscript are freely available on the Digital Library.

– James Freeman

For fragments of a quadrilingual Psalter, on view in London this weekend, and being sold in New York next month, see here: http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2016/bible-collection-of-charles-caldwell-ryrie-n09539/lot.4.html