The Peterborough Cathedral Manuscripts and the Peterborough Lapidary

Guest post by Dr Francis Young

In 1970 Peterborough Cathedral placed its ancient manuscripts on permanent loan to Cambridge University Library, owing to the unsuitable conditions in which the Cathedral Library was then housed (in a former chapel above the Cathedral’s west porch). The University Library thereby became the custodian of an important collection (now catalogued under the classmark ‘Peterborough Cathedral’) with an unusual history. Henry VIII erected Peterborough Cathedral in 1541 immediately following the dissolution of Peterborough Abbey, with the last abbot as the first bishop and most of the former monks of the monastic chapter as canons of the new cathedral chapter. Peterborough therefore experienced an unusual degree of continuity, and this included the survival of the old monastic library which was then located above the cloister.

Unfortunately, in 1643 Oliver Cromwell’s army sacked Peterborough on its way to besiege the Royalist stronghold at Crowland. The soldiers ransacked the library for anything they thought looked like a papal bull (any scroll with a large seal on it) or a Catholic service book (any book written in Latin was at risk). In a few cases, members of the chapter were able to buy back valuable books from the soldiers who had stolen them, but the damage to the library was extensive, and later that year Parliament ordered the demolition of most of the former conventual buildings including the outer arcade of the cloister and the rooms above it, where the library was located. It is not known what became of the surviving books between 1643 and 1672, when a new library was established in the Cathedral’s fan-vaulted sixteenth-century retrochoir (known as the ‘New Building’). It is possible that they were preserved somewhere in the Cathedral precincts or even kept for safekeeping by citizens of Peterborough. Either way, it is certain that the library survived in some form and that the medieval collection was not completely destroyed.

In 1708 the energetic antiquary White Kennett (1660–1728) became Dean of Peterborough and made it a priority to rebuild the Cathedral’s library collection, if necessary by buying back books alienated from the library during the chaos of the Civil War and Interregnum. White also catalogued the library, and surviving manuscripts in the Peterborough Cathedral collection are still catalogued under the classmarks assigned to them by White in a distinctive early modern hand on the first folio of each manuscript. Although it is possible to cross-reference books in the surviving collection with those listed in a fourteenth-century Matricularium of the monastic library, we cannot know whether White had to reacquire these books or whether they were always at Peterborough. Furthermore, we have no way of knowing which fifteenth- and sixteenth- century manuscripts were in the monastic library because no later medieval catalogue survives, and White did not make a record of his acquisitions and their provenances.

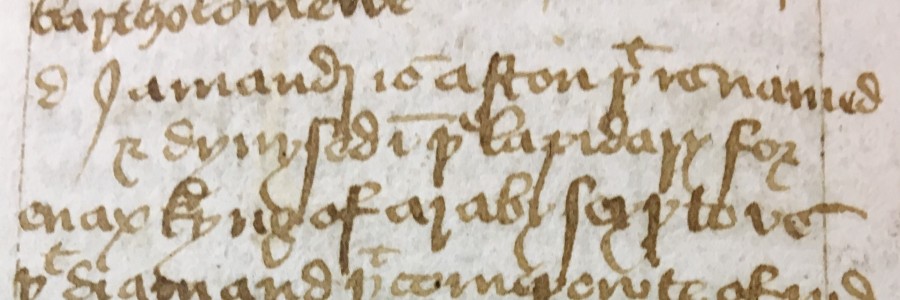

At some point before 1933 two scholars of Middle English literature, Joan Evans and Mary Serjeantson, discovered in Peterborough Cathedral library the longest treatise on the magical and medicinal properties of stones ever composed in Middle English. The original text of the late fifteenth-century ‘Peterborough Lapidary’ (part of MS Peterborough Cathedral 33), which is four times longer than any other known English lapidary, was published by the Early English Texts Society. A new edition of the Peterborough Lapidary, accompanied for the first time by a translation into modern English, has recently been published which corrects a small number of errors of transcription and/or interpretation in Evans’ and Serjeantson’s edition. A Medieval Book of Magical Stones: The Peterborough Lapidary also provides the first thorough exploration of the Peterborough lapidary’s possible origins and sets the text in the context of medieval science, medicine and magic as well as the latest scholarship on lapidaries.

The lapidary takes the form of a roughly alphabetical encyclopaedia of 145 stones (really 128 since the compiler repeats some of them), both real and mythical, including recognisable precious and semi-precious gems alongside otoliths (mineral-like accretions in the bodies of animals) and even manmade substances like glass. Each entry describes the properties of the stone or mineral if it is carried, rubbed, tasted, ground up, ingested or burnt. Many of the properties are magical, including divination, command over demons, protection against witchcraft and communication with the dead, but around a third of the properties described are medical. Cures for eye complaints are the most common, although reproductive medicine including stones to promote conception, ease childbirth and facilitate lactation is also very prominent. However, the lapidary also hints at the beginnings a ‘scientific’ understanding of stones established by direct experience rather than ancient authority, and the author shows an interest in static electricity and condensation as well as the formation and origins of stones.

The Peterborough Lapidary is neither particularly original nor critically composed, but its scale in comparison with other lapidaries shows that, in this case, an attempt was being made to construct a complete English encyclopaedia of the properties of stones. The fact that the text was bound together with other materia medica in MS Peterborough Cathedral 33, including an alphabetical antidotarium (list of antidotes to poisons) may mean that it formed part of the medical collection of the monks of Peterborough Abbey. It is also possible that the manuscript was acquired anew by Kennett White after 1708, but the manuscript’s nondescript appearance and the fact that it was in English (meaning it could not be mistaken for a Catholic service book) mean that it could have survived the disastrous sacking of 1643. Neither the content of the text nor the physical manuscript provide any clues, but the Peterborough Lapidary occupies a special place among the numerous medieval English lapidaries as the most ambitious and extensive example of the genre.