Solomon Negri and the ‘Marvels of Creation’

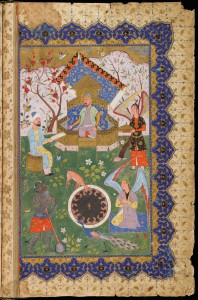

Displayed in the ‘Curious objects’ exhibition is one of the finest illuminated manuscripts in the Library’s Islamic collection. It is a copy of the Persian version of Qazwini’s ʻAjāʼib al-makhlūqāt wa-gharāʼib al-mawjūdāt, or “The marvels of creation and the oddities of existence”, commonly known as “The cosmography of Qazwini”.

This very special manuscript has always been connected with the collection of Persian and Arabic manuscripts donated by the Reverend George Lewis in 1727 in housed in a special wooden cabinet, which is now located on the fourth floor landing of the Library. However, this particular volume was donated to the Library at a somewhat later time, in 1770, by the son of George Lewis. It was placed in the Lewis Cabinet, situated at that time in the Dome Room of the old University Library building next to the Senate House. George Lewis served as Chaplain to the East India Company in Fort St George, Madras from 1692 to 1714. He had become very interested in teaching, in missionary work and in translating and printing copies of the Bible into Arabic, Persian and other languages.

The original author of the ‘Marvels of Creation’, Zakariya Qazwini, was born in Qazwin, Iran in 1203 CE. He served as a legal expert and judge in Iran before travelling around the Levant, finally becoming a member of the circle of Ata-Malik Juvayni, the governor of Baghdad (d. 1283 CE). It was to the latter that Qazwini dedicated his work, in he form of an Arabic treatise, which was frequently illustrated, immensely popular and later translated into Persian. The Library’s manuscript is a 16th century copy of the Persian text and is very finely illuminated throughout.

The first section of the text describes the celestial spheres, the stars, and the 12 signs of the Zodiac, followed by the “Guardians of the Kingdom of God” and other angels. The second section of the work describes the sub-lunar sphere including minerals, plants and the animal kingdom, including human beings and their cultures. There are numerous illustrations of commonly known mammals, birds, insects and reptiles, along with strange beings, which conclude the text.

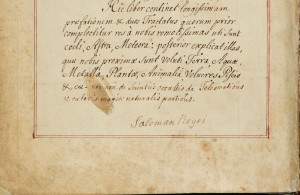

Further investigations reveal that on the manuscript’s very last page, and easy to miss, is a long Latin description of the manuscript’s origins, its author, title and something of the contents of the magnificent volume. At the foot of the description, and obviously its writer, is the signature of the Arabic scholar Solomon Negri, an obvious indication that the manuscript had been known to him. But how had this connection between George Lewis, Solomon Negri and the Qazwini manuscript come about?

Solomon Negri, also known as Sulaiman ibn Ya’kub Al-Shamì Al-Salihani, was born in Damascus in 1665; he would have been a contemporary of George Lewis. He had learnt Greek and Latin from Jesuit missionaries and he later travelled widely in Europe, including in Paris where he continued his studies at the Sorbonne. He also spent time in London and, in 1701, visited Halle where he remained for four years giving lessons in Arabic, among others, to the orientalists Christian Benedikt Michaelis and Johann Heinrich Callenberg

However, living in Germany did not suit his health and he returned to Constantinople where he was ordained a priest in the Greek Church. After further travels he returned again to London where he obtained employment as an interpreter of oriental languages until his death in 1727. Negri’s special interests lay in teaching the languages of the Middle East, especially focussing on projects to translate the Bible into Arabic.

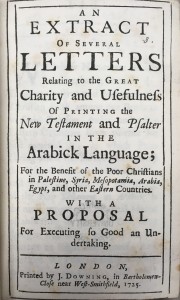

Printed in London in 1725, was a collection of ‘several letters relating to the great charity and usefulness of printing the New Testament and Psalter in the Arabick language for the benefit of the poor Christians in Palestine … and other Eastern Countries …’ in which there is a letter from Solomon Negri to the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (SPCK) dated 1720, strongly supporting such a translation project.

Further letters in the same volume are written by other interested parties, mainly members of the clergy. Among them is a letter from George Lewis, also dated 1720, now returned from his duties in India and, at the time, resident in London. During his time as Chaplain to the East India Company in Madras, George Lewis also supported the translation and printing of the Bible into Arabic and Persian and was a keen supporter, like Negri, of such projects. Lewis was also a corresponding member of the SPCK. He had been involved with the establishment of the very earliest printing press in India imported specially for the printing of Bibles for distribution by missionaries.

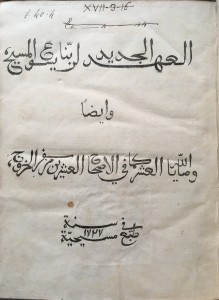

Negri’s plans did indeed come to fruition and he wrote translations of the Psalms and the New Testament published under the auspices of the SPCK. The Psalms appeared in 1725 and the New Testament in 1727.

So it is highly likely that Solomon Negri and George Lewis, with their common enthusiasms for translating, teaching and missionary work, became acquainted in London during the last ten years of Negri’s life. Probably, Negri knew of Lewis’s manuscript collection, which may well have been stored in London at the time, before its transfer to Cambridge. Perhaps Negri even saw the Lewis cabinet and was impressed by its contents.

George Lewis himself had departed to Ireland to be Archdeacon of Meath in 1723, shortly after these letters were written to the SPCK, so perhaps that is the explanation as to why the Qazwini manuscript was given to his son, probably still resident in London, and remained with him. The son may well have died around 1770 with manuscript still in his possession, and after which, it came to the Library to join the other manuscripts formerly belonging to his father in our Lewis ‘Cabinet of Curiosities’.