The ‘Album amicorum’ of Abraham Ortelius

Engraved portrait of Abraham Ortelius; possibly early 17th century; National Portrait Gallery, NPG D25672

The latest addition to the Cambridge Digital Library is the Album amicorum of Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598). The Album amicorum – literally ‘book of friends’ – belongs not to the University Library but to Pembroke College. It is one of a growing number of manuscripts and books from collections across Cambridge that have been photographed by our Digital Content Unit, with the images and full descriptions now hosted on the Digital Library.

Abraham Ortelius is best known today as the creator of the first modern atlas, the Theatrum orbis terrarum, first published in 1570. The ‘Catalogus auctorum’ that accompanied the Theatrum was also the first printed list of cartographers and their maps. It delineates many of the sources from which Ortelius’s own work was ultimately compiled, providing a window into his intellectual hinterland.

Ortelius had in fact begun his cartographical career out of economic necessity: the early death of his father, when Abraham was only twelve, prompted his mother to make a living selling antiques, with Abraham and his sisters Anne and Elizabeth contributing to the family income by hand-colouring maps.

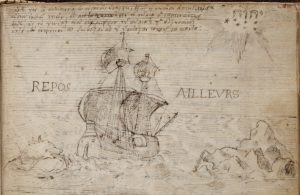

Drawing of a ship navigating between Scylla and Charybdis, added by Philips van Marnix van St Aldegonde; Pembroke College, MS LC.2.113, f. 43r

Admitted in 1547 to the painters’ Guild of St Luke, Ortelius progressed to dealing in antiques, coins and particularly maps and books. The proceeds from these apparently successful enterprises he deployed in developing his own collections, probably inspired at least in part by the ‘cabinets of curiosity’ belonging to the intellectuals and antiquarians he met during his European travels.

Commerce took Ortelius across Europe – notably to book fairs in Frankfurt, but also to Paris, London and elsewhere – and his scholarly contacts were similarly wide-ranging. An active figure in the early modern ‘Republic of Letters’, Ortelius left behind a large archive of letters. Unfortunately, these were dispersed at auction in 1968, but scholars such as Joost Depuydt are now actively engaged in tracing them in libraries and archives across the world and many are now indexed as part of the Early Modern Letters Online project.

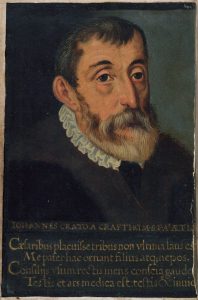

Painted portrait of Johannes Crato von Crafftheim, dated c. 1579/80; Pembroke College, MS LC.2.113, f. 12v

Engraved portrait of Johannes Crato von Crafftheim, dated 1574; Pembroke College, MS LC.2.113, f. 9r

Many of Ortelius’s correspondents also made contributions to the Album amicorum, over the course of a quarter of a century; the earliest addition is dated 1574 and Ortelius continued to collect contributions until his death in 1598. Entries range from fine portraits painted in miniature down to brief inscriptions in less-than-tidy handwriting. For example, Johannes Crato von Crafftheim (1519-1585), court physician to Holy Roman Emperors Ferdinand I, Maximilian II and Rudolph II, appears twice in the volume: first, in an engraved portrait dated 1574; second, in a portrait made when the sitter was aged sixty or perhaps sixty-one (around 1579 or 1580), juxtaposed with an inscription dated 1584.

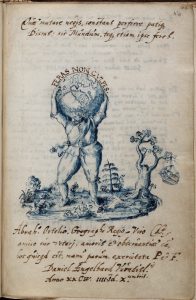

Sketch in blue ink of Atlas holding the world on his shoulders, amidst a naturalistic foreground, with the inscription of Daniel Engelhardt; Pembroke College, MS LC.2.113, f. 54r

Some inscriptions were accompanied by sketches. Daniel Engelhard (1569-1635) made his first inscription on 12th September 1577, at Frankfurt-am-Main. His second, made on 10th December 1584, incorporated a drawing of Atlas carrying the globe on his shoulders (presumably in tribute to Ortelius’s work as a geographer).

Drawing in grisaille of Alexander the Great and Diogenes, with the inscription of Laevinius Torrentius; Pembroke College, MS LC.2.113, f. 11v

Laevinius Torrentius‘s entry includes a drawing in grisaille of Alexander the Great and Diogenes. According to classical legend, Alexander visited the philosopher and asked if he wanted anything; Diogenes’ response – ‘Not to stand in the way of the sun’ that he had been enjoying – indicated his detachment and lack of interest in worldly affairs. The inclusion of the story was doubtless intended as a compliment to Ortelius’s own devotion to scholarship.

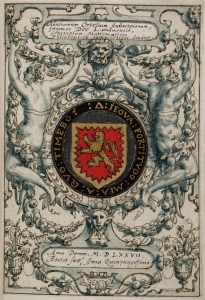

There are some familiar names within the pages of the Album amicorum: perhaps the most famous, in this country at least, is that of John Dee (1527-1609), the mathematician, astrologer and antiquary. Dee had his coat of arms painted into an ornamental cartouche, writing that he embraced Ortelius with love (‘complectetur amore’), and dated his contribution to 1577, his fiftieth year. That same year on 21st September, another English antiquarian, William Camden, added a sketch and a lengthy poetic inscription, concluding with the motto ‘Maximo amori maximus timor iunctus’: ‘With the greatest love the greatest respect is joined’.

Ornamental cartouche containing the inscription of John Dee, with his coat of arms painted into the central roundel; Pembroke College, MS LC.2.113, f. 90r

Dee’s inscription was one of forty-five inscriptions incorporated into ornamental cartouches (seven other such cartouches were left unfilled). Painted by hand and pasted into the volume, presumably at Ortelius’s instruction, these borders are filled with elaborate, classically inspired architectural features: scrollwork, busts and heads, putti and human figures, foliage, flowers, cornucopia, animals, canopies, and so on.

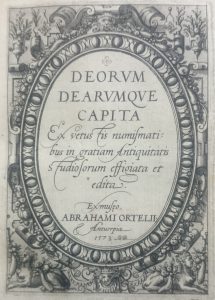

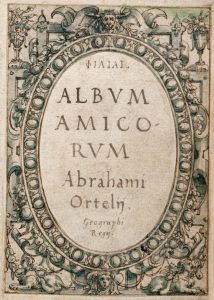

Many bear a close resemblance – and were likely inspired by – the borders found in another of Ortelius’s publications: the Deorum dearumque capita (‘The heads of gods and goddesses’), first published c. 1573. Indeed, the frontispiece to the Album amicorum is directly modelled on the title-page of the Deorum. This numismatical work comprised a series of fifty-five engravings, depicting medallion portraits of ancient gods and personifications, and is witness to another aspect of Ortelius’s scholarship.

The Album amicorum provides a snapshot of the breadth and variety of Ortelius’s contacts with fellow intellectuals: cartographers, cosmographers, explorers, artists, historians, physicians, lawyers, lecturers and humanists. These men were scattered across Europe: additions to the Album were made in Frankfurt-am-Main, Breslau, Antwerp, London, Richmond, Holstein, Leiden, Bruges, Vienna and other places. The book often accompanied Ortelius on his travels, bearing witness to the remarkable degree of mobility scholars and artists enjoyed at a time when modes of transport were slow, unreliable or even perilous.

Frontispiece to the 1582 edition of the ‘Deorum dearumque capita’; CUL, F158.d.6.2

Some of the tributes might sound a little flowery to modern ears, the praise a little fulsome, but such expressions of friendship were a vital constituent of humanistic endeavour in the early modern period. The emotions they record were without doubt felt in all sincerity: taking inspiration from the classical period, as in so much else, the humanists saw friendship as a social and intellectual cohesive, holding learned society together. Ortelius’s little ‘book of friends’ reveals a truly European, supra-national Weltanschauung: by cultivating a sense of engagement in shared intellectual enterprises, the obstacles presented by borders, languages and politics might be surmounted, in the spirit of amity, collaboration and unity.

Pingback: Merkwaardig (week 11) | www.weyerman.nl

Hello,

Thank you for the great work you do. I am currently looking at the Album amicorum of Abraham Ortelius, and I noticed that some of the pages are missing their description.

I am only halfway through, but I noticed that (image 55, page 26r) and (image 97, page 46r) are not in the contents list.

Dear Leticia,

Thank you for your message.

In preparing the description for this manuscript, I grouped together pages that were inscribed by the same person. In both of these instances, Guido Laurin and Louis Carrio wrote messages across the opening of the manuscript: first on the blank verso of one leaf and then within the ornamental cartouche on the recto of the following leaf. Descriptions of folios 26r and 46r therefore come under descriptions of folios 25v and 45v respectively – although at first glance it looks like they have been omitted from the list given under the Contents tab.

If you return to the About tab and scroll down to the bottom, there you will find the full details of what is featured on that page. Where a textual item stretches across a range of folios, those details persist as you navigate back and forth through the manuscript.

We are aware that the Digital Library’s display of information relating to the textual contents of a manuscript could be clearer!

Best wishes,

James Freeman

Medieval Manuscripts Specialist

Dear James,

thankyou found this very interesting. I am currently writing a thesis on autograph albums of WW1 and would apprciate it if I can cite your article in support of my background work on the autograph album. Can I ask the best way to cite your piece please?

many thanks

Rebekah SloaneMather (PhD Student Cardiff University)

Dear Rebekah,

Thank you for your message. I’m glad you found this post of interest. Perhaps the best way to cite it is as follows:

James Freeman, ‘The “Album Amicorum” of Abraham Ortelius’, Cambridge University Library Special Collections Blog, 4 March 2017 <https://specialcollections-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/?p=14031>

There are not currently DOIs for posts on the blog, unfortunately, so you may wish to provide the URL of the blog’s main page rather than this specific post, since there is less risk of the link breaking.

Best wishes,

James