Egypt on a tourist’s mind

A guest post by Jasmin Daam, University of Kassel

The emergence of tourism, i.e. an organised way of travelling, in the second half of the nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries is related to a variety of developments, among others the possibility of temporarily leaving one’s workplace, the availability and affordability of transport infrastructures and accommodation, as well as the interest in remote places. Egypt was one of the early non-European destinations to attract tourists; it has been part of the tour operator Thomas Cook’s portfolio since the nineteenth century. Initially a playground for European elites who spent the winter months in the south, the country on the Nile had become accessible to a broader range of travellers by the interwar period.

At first sight, tourists relying on well-trodden paths of tour operators appear less fascinating than the heroic adventures of solitary explorers, and the lightness of tourists’ experiences seems to have disqualified tourism as an object of serious historical study until recently. However, tourism is an interesting case of individual movements becoming a well-institutionalised structure. After all, the growing amount of travellers established a stable connection between their country of origin and the destination. This relationship was continuously shaped and re-shaped due to the individual tourists’ mobility. As visuality plays a key role in tourism, it might be promising to recur to visual sources in order to analyse such relationships. Already in the 1920s and 1930s, light cameras had become a standard tourist accessory: “to kodak” was used as a verb, describing the practice of taking snapshots in remote and exotic regions of the world in order to show them to friends and relatives at home. To the historian though, mostly trained in the analysis of textual sources, the pictures, and particularly amateur photographs, need to be handled with methodological care. As we ‘read’ images in a more intuitive way compared to texts, we need to figure out how they work and what kind of information they comprise.

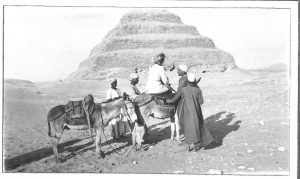

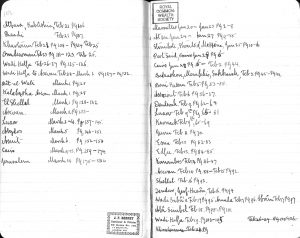

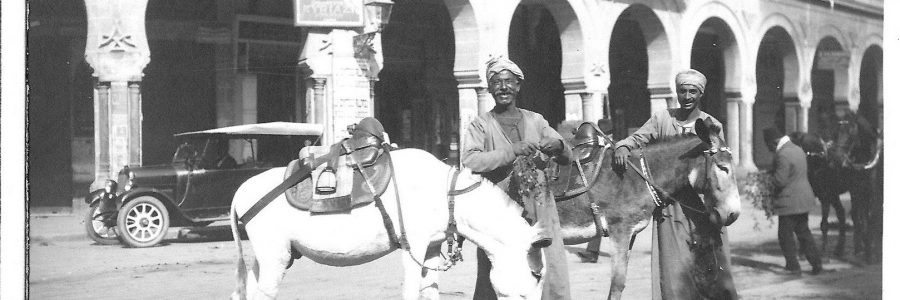

A particularly interesting document, part of the collection of the Royal Commonwealth Society, may be able to give a few hints at our understanding of amateur photography: Among the collection of photograph albums of George H. Williams (1893–1975), partner in a drapery firm, his album on Egypt is accompanied by the diary he was keeping during the same trip. He undertook the three-month voyage from January to March 1925 together with his father, Howard. After having arrived in Egypt, they embarked in Cairo and travelled up the Nile on one of Thomas Cook’s famous Nile steamers. Williams visited the famous monuments and sites of Egyptian antiquity, for example Abu Simbel and Luxor, but the majority of the photographs represent picturesque scenes of Egyptian daily life. There are pictures of pyramids and hieroglyphs, but it is the “ethnographic tradition” of photography[1] that prevails in his album, the representation of inhabitants of rural Egypt, of their simple lifestyles, clothing habits and other customs. Thus, the photographs represent the Orientalist vision of the East that has been abundantly analysed and criticised since the publication of Edward Said’s “Orientalism”: The ‘Oriental’ inhabitants are essentialised, Egyptian progress and modernity either denied or ignored and the country is represented as the West’s opponent, which may carry connotations of inferiority, as Said claims, or idealisation, as John MacKenzie replies.[2]

In his diary, the author describes the trip and his impressions; but he also comments on the various sights and the photographs taken. A comparison of the images in the photograph album and in the written text reveals a two-fold divergence between the representations of Egypt. First, when Williams describes his photographs’ motifs, he mentions mostly monuments, temples and statues. In contrast, the pictures in Williams’ album mainly show an ‘Orientalist gaze’, i.e. images of rural Egypt and its inhabitants. Second, the textual memories display an Egyptian modernity which is not or barely visible in the album. George H. Williams hints at recent political developments, demonstrations and upheaval, he observes changes in lifestyle like cyclists and cafés in Cairo, whereas street traffic in his visual representations is limited to carriages pulled by donkeys. Thus, his textual reflections demonstrate that he is well aware of transformation processes going on in Egyptian society, even though they are not captured in his photographs.

To conclude, the comparison of the written text and the visual memories reveals an ambiguity of perception which seems to be linked to the textual and visual characteristics of the sources. Whereas Williams reproduces Orientalist clichés in the pictures he takes, he considers the Egyptian realities of the 1920s in his text. This contradiction might be due to the fact that visual impressions and therefore the production of images occur prior to reflection.[3] Hence, Williams’ camera captured the familiar exotica he already had in mind before he even left Great Britain. Only when noting down his thoughts in the diary, he questioned, interpreted or relativized his first visual impressions. He perceived the country’s complexity, which he did not represent visually. Thus, his relatives and friends at home, who admired the photographs without having access to the diary, obtained a partial and incomplete idea of Williams’ image of Egypt. Ultimately, the spread of visual material representing remote regions in the early twentieth century might explain the fact that Orientalist stereotypes still prevailed in the British imagination of the East, even though an increasing number of Europeans actually travelled to these countries where they were confronted with rapidly transforming societies. As this knowledge, however, remained confined to written texts, it did not change the minds of the people who remained at home, and their imaginaries of a backward Orient were confirmed by the photographs tourists like George H. Williams brought back home.

George H. Williams, Collection on Egypt 1925. RCS/GBR/0115/Y3041D

George H. Williams, Travel Diaries. Egypt 1925. RCS/RCMS 53/3/1

Jasmin Daam

Teaching and research assistant (Global History; University of Kassel)

Ph.D. project: Tourist Spaces. The Arab East as European tourist destination in the interwar period

[1] Derek Gregory, “Emperors of the gaze. Photographic practices and productions of space in Egypt, 1839–1914”, in: Joan M. Schwartz/James R. Ryan (eds.), Picturing place. Photography and the geographical imagination, London 2009, S. 195–225.

[2] Edward W. Said, Orientalism, London 2003 [1978]. John M. MacKenzie, Orientalism. History, theory, and the arts, Manchester/New York 1995. For a discussion on the notion of time in processes of Othering see Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other. How anthropology makes its object, New York 2014 [1983].

[3] Ralf Bohnsack, “Disziplinierte Zugänge zum undisziplinierten Bild. Die Dokumentarische Methode”, in: Thomas Abel/Martin Roman Deppner (Hrsg.), Undisziplinierte Bilder. Fotografie als dialogische Struktur, Bielefeld 2013, S. 61–103.