Rebinding the Red Book of Thorney

By Shaun Thompson

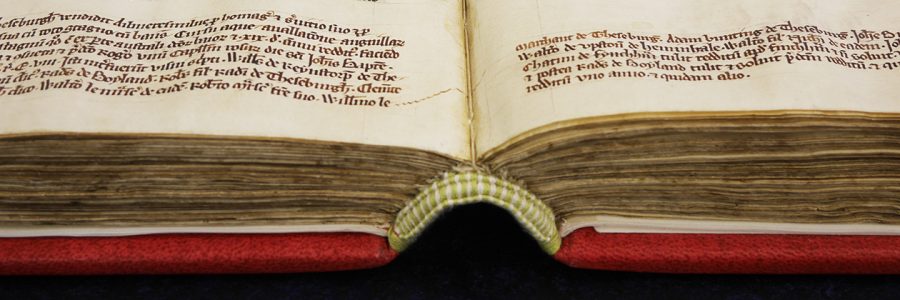

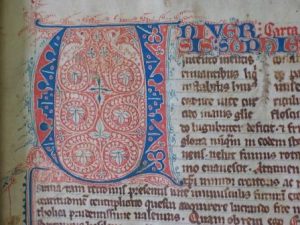

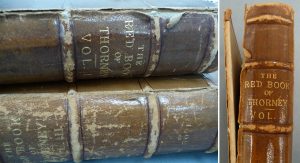

The Red Book of Thorney is an early fourteenth-century cartulary originally from Thorney Abbey in Cambridgeshire. It was donated to Cambridge University Library by Samuel Sanders at the end of the nineteenth century. The medieval manuscript consists of 467 parchment leaves some of which are illuminated. The Red Book of Thorney would have originally been bound in a monastic setting by a highly skilled bookbinder using the highest quality materials. It was rebound into two volumes in 1889/90 by Stoakley (late Hawes) of Cambridge.

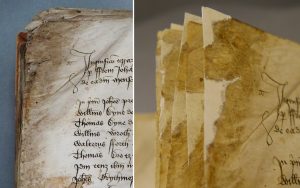

Many early books that remain in their original bindings have survived in excellent condition. However, a significant number of medieval books, including the Red Book of Thorney, were re-bound in the nineteenth century by bookbinders using techniques which are not appropriate for parchment manuscripts. The Red Book of Thorney’s binding had severely restricted the opening characteristics of the book causing mechanical, chemical and structural damage. The structure itself was beginning to significantly break down, providing very little protection to the text-block and making access increasingly difficult.

Dr. Sandra Raban, who has a particular scholarly interest in the Red Book of Thorney, had noticed a significant change in its condition. She made a generous donation through the Friends of the Library, with the intention that this would contribute to the conservation of the manuscript.

After discussion with the Head of Conservation, Keeper of Manuscripts and colleagues in Conservation and Collection Care, it was decided that the Red Book of Thorney should be dis-bound, repaired, resewn and rebound. The aim would be to create a working, functional object using techniques from the medieval period that complement the parchment text-block.

CONSERVATION TREATMENT

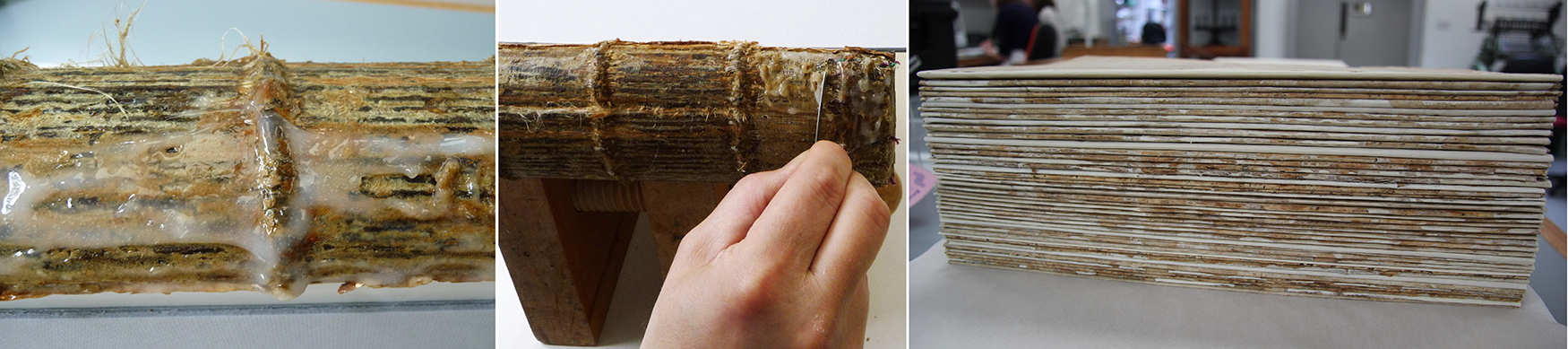

The old covering leather and animal glue on the spine were softened with a wheat starch paste poultice and mechanically removed using a fine spatula and bone folder. The sewing threads were cut at the centre folds of each gathering and the thread was pulled through the spine folds, to free the gatherings from the sewing supports, before they were separated. This process revealed the damaged caused by rounding, backing and the application of hot animal glue which had been carried out during the nineteenth-century binding process.

All of the damaging repairs were carefully removed. Tears were repaired and infills were introduced, using cold gelatine mousse as the adhesive and caecum as the repair material. These materials were selected for their physical characteristics and for the like-for-like properties with parchment; this ensured the creation of subtle repairs that are sympathetic to the original materials and place minimal strain on the original parchment leaves. Gelatine mousse is a gelatine solution which is allowed to cool and gel and is then aerated by passing it through a fine mesh. Caecum is alum-tawed goldbeaters skin which is produced from the intestine of a cow, using parchment-making techniques. It is produced in three different thicknesses and can be layered to achieve a suitable thickness for repair. The caecum was shaped and feathered so as to ensure good adhesion and the creation of a gentle transition of the repair to the original leaf.

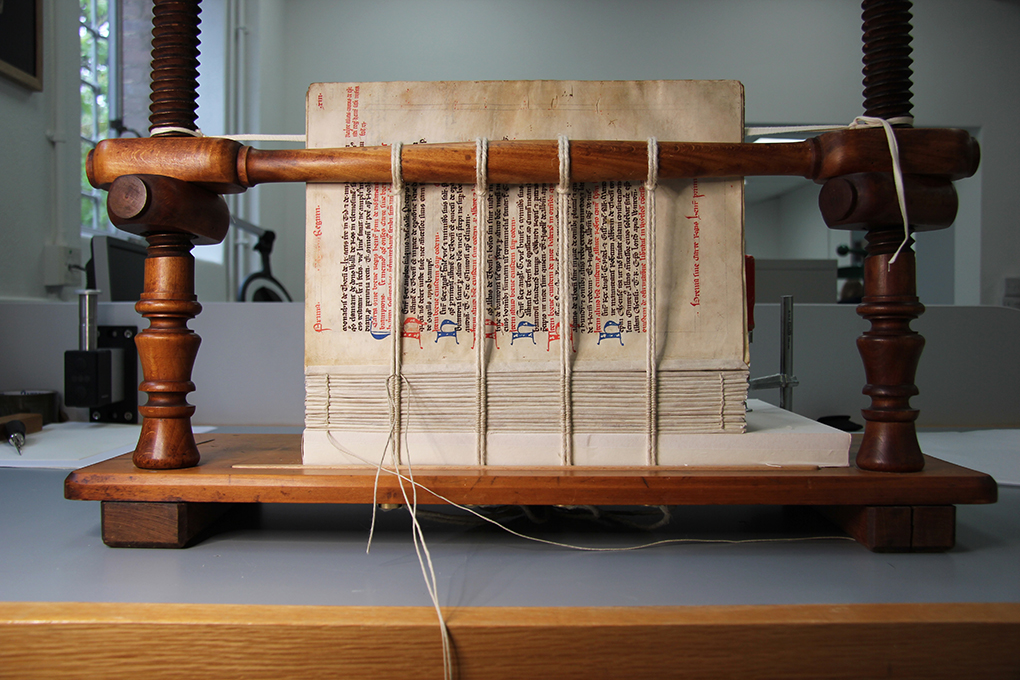

The gatherings were sewn on double 8-ply linen cord sewing supports, the technique of half-packed sewing which allows the tension created in the sewing process to be trapped underneath the turns of the thread. This trapped energy is transferred along the supports and acts much like a spring and thus distributes stresses evenly.

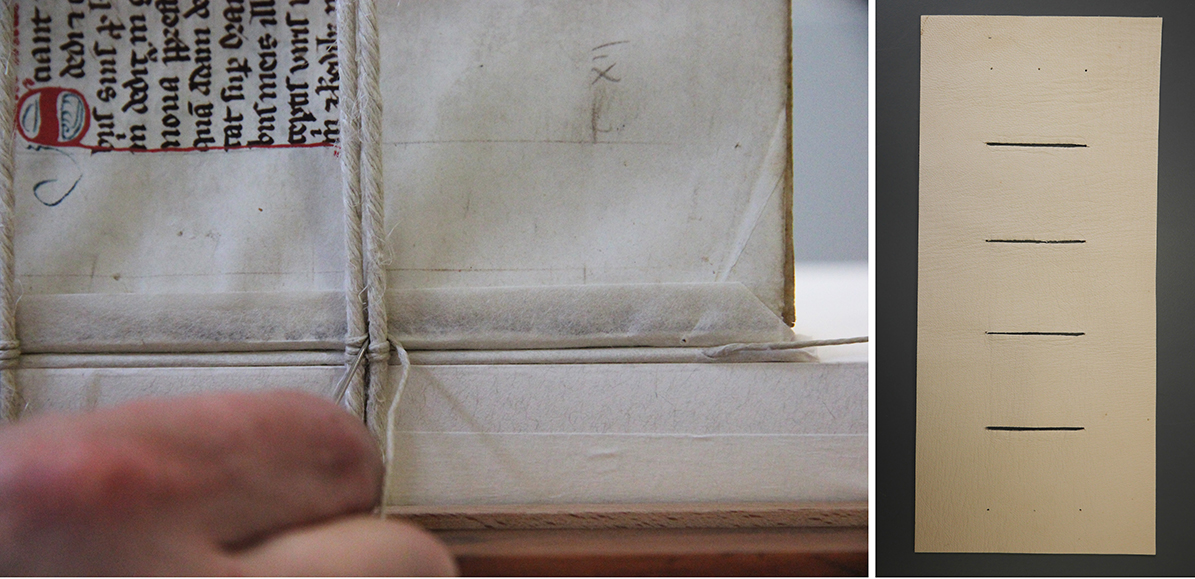

Once the sewing process was complete, a ‘bonnet’ made of alum-tawed goat skin was added to the spine. The bonnet is a non-adhesive spine liner. The alum-tawed skin was slit to correspond to the sewing stations; it was attached by placing it over the sewing supports which were pulled through the slit skin, thereby locking the bonnet in place. The bonnet is not adhered to the spine. Primary endbands were sewn through the spine folds and the bonnet onto an 8-ply linen core. As well as protecting the parchment from the adhesive, applied to the covering material, the bonnet also contributes to the mechanical function of the binding.

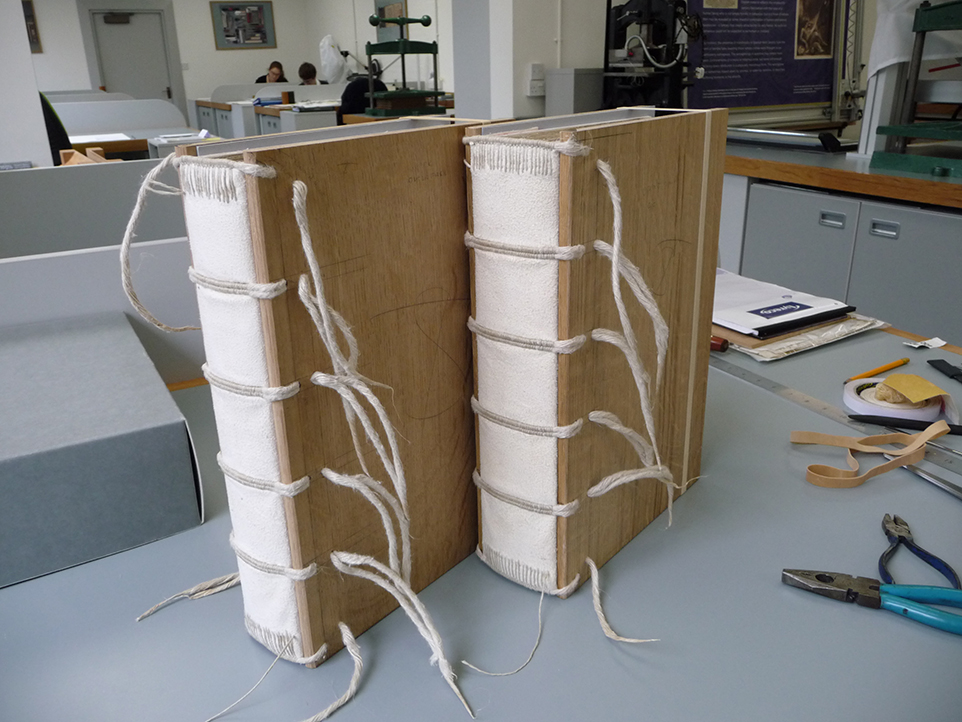

New wooden boards were worked from 12mm quarter-sawn oak, cushioned on the outer surface and gently bevelled on the inner surface. The sewing supports and the endband cores, were laced in to the boards and pegged in place.

Alum-tawed goatskin was selected as the covering material. A red stain was created using Brazilwood and a base made from potash which, when processed, can achieve a palette of colour from pinkish reds to red/violets. Once the stain was prepared it was painted onto the skins using a large brush.

The skins were then hung up to dry. The process was repeated until the desired depth of colour was achieved.

Following the staining process, which made the skins hard and inflexible, the skins were ‘boarded’ to loosen the fibre bundles. The boarding process ensured that the skin was flexible enough for covering.

The cover was attached to the book using wheat starch paste which was applied to the flesh side of the skin. The skin was then moulded over the spine bonnet, sewing supports and boards; the corners were mitred. The book was ‘tied-up’ and bandaged for a short while to ensure that the skin was securely adhered.

A secondary end-band was sewn through the covering at the head and tail. This serves to secure the covering material to the spine of the book. It is also a further mechanical attachment which strengthens the structure, supporting the arching of the text-block when opened.

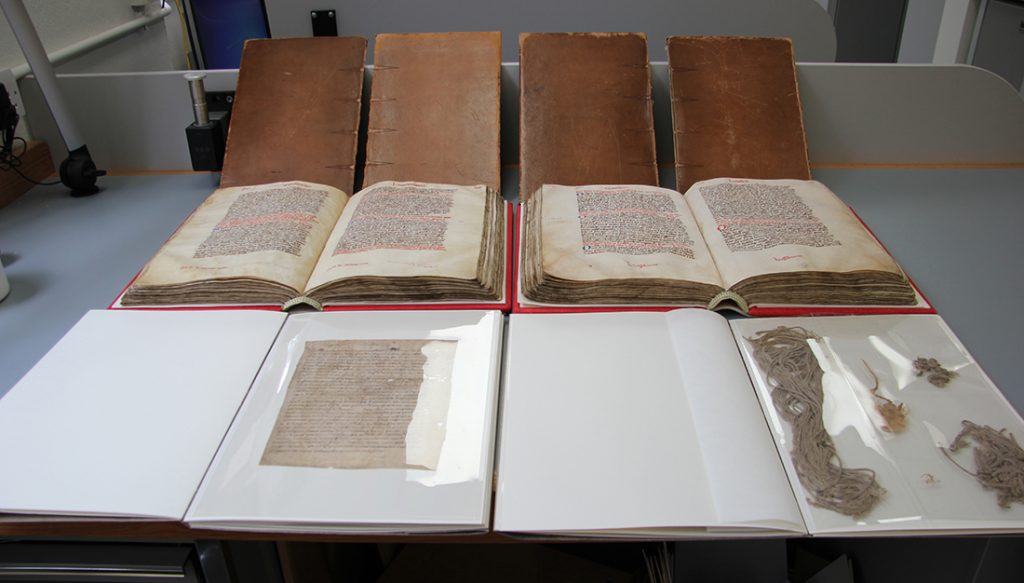

Materials salvaged from the nineteenth-century binding were encapsulated into polyester and sewn into a non-adhesive, long-stitch book format with alum-tawed spine reinforcements and flax paper covers. They are stored alongside the manuscripts.

All the bookbinding techniques used were adapted from the medieval period, when the importance of understanding materials was crucial to the structural concept of bookbinding. The Red Book of Thorney is now well conserved, open easily and is fully accessible for research. The manuscript has been digitised and can be viewed from cover-to-cover on the Cambridge Digital Library.

Click here to see a video of me rebinding the Red Book of Thorney.

With special thanks to Dr Sandra and Tony Raban; Abigail Quandt from the Walters Art Museum; Jiri Vnoucek from the Royal Library Copenhagen; Edward Cheese from the Fitzwilliam Museum; Henk de Groot, parchment maker; Antoinette Curtis, conservator and my colleagues at Cambridge University Library.

Wow, so Wonderful!