Newly-identified Cypriot letter: guest post by Vasiliki Vartholomaiou

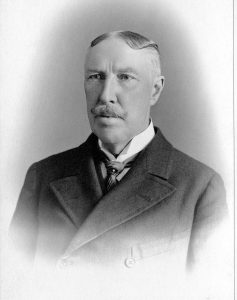

One of the great treasures of the Royal Commonwealth Society Library is the Claude Delaval Cobham collection of books, pamphlets, maps and photographs relating to Cyprus. Cobham served as Commissioner of the District of Larnaca from 1879-1907 and devoted much of his life to studying the island’s dramatic history. We are very grateful to our Cypriot colleague in the Manuscripts Reading Room, Vasiliki Vartholomaiou, for the interest she has taken in the collection. Vasiliki has translated and researched the copy of a previously unidentified letter written in Greek (Y3018I/6). A copy of the translation has been filed with the letter. Vasiliki writes:

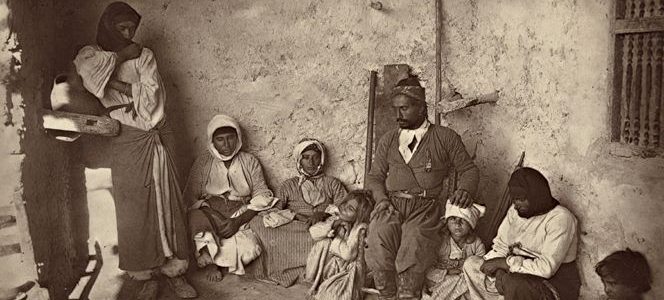

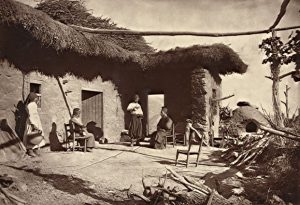

This letter has led me on an amazing journey in searching for the historical figures it mentions, and in looking at it linguistically as well as historically. It has led me through my country’s own history during a time that I have only read of in history books, or heard through stories passed down through generations. The letter, probably dated 5 December 1821, was written during a turbulent time in Cypriot history. It gives insight into Greek Cypriot support for the Greek War of Independence against Ottoman rule, which began on 25 March 1821; this support ultimately led to the hanging of Kyprianos, Archbishop of Cyprus, on 9 July 1821. From previous centuries, a significant number of letters (which can be found in the archives of the Archdiocese of Cyprus) had been sent from Greek Cypriot Bishops to the Kings of Spain, the Duke of Savoy and to the Dukes of Venice seeking support in freeing Cyprus from the Ottomons. Unfortunately, the ruling princes of Europe were unwilling to respond to these appeals.

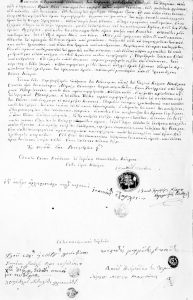

I am going to examine the use of language and how it informs our understanding of the struggles of the Cypriot people at this time. The letter is signed with the stamp of Spiridon, the Bishop of Trymithountos, who had successfully escaped the Ottoman massacre of Greek Cypriots and fled to Europe along with other distinguished Greek Cypriots to work for the freedom of their people. The letter begins by expressing the hardships of the Cypriot people during the ‘η τυραννική διοίκησις των Τούρκων’ (tyrannical rule of the Ottomans) who had made daily life unbearable, had put Christians to death, pillaged property, kidnapped women and converted Greek Cypriot children to Islam. They had not respected the Greek Cypriots of all ranks, including the Archbishop of Cyprus ‘ουδέ των σεβασμίων Αρχιερέων ουδ’ αυτού του Μακαριωτάτου ημών Πατρός και Δεσπότου’ who was the highest authority during that period. In the letter the Ottomans are represented as ‘ληστάς’ (thieves), ‘τυράννων’ (tyrants) and ‘αιμοβόρους λυκους’ (bloodthirsty wolves).

The first paragraph ends with a reference to ‘αδελφούς ημών Έλληνας’ (our Greek brothers) which I believe is a reference to the Greek revolution of 1821. By that time it probably had become evident that there would be no armed revolution in Cyprus, but the Greek Cypriots would still provide assistance to support the Greeks. Ottoman losses during the Greek revolution created a backlash against the Greek Cypriots. Cyprus is described as ‘τρισαθλίας νήσου Κύπρου’ (three times miserable) where previously it had been called ‘μακαρίας,’ a word that means longevity but in this case translated into happiness.

The second paragraph gives us the purpose of the letter. It nominates Nikolaos, who has the title ‘Οικονόμου’ (Oikonomou, a title for someone who had worked close to the Archbishop of Cyprus). He has been given ‘πληρεξουσίως’ (power of attorney, complete control) over the properties listed. There seems to have been additional financial support gathered by the signatories. This is suggested by the inclusion of mosques which would usually be under the control of the Ottomans. With this property Nikolaos has the means to proceed with any action that will help the Cypriot people. The Greek Cypriot people at this time did not have the necessary support to follow the Greeks in a revolt against the Ottomans, hence the letter highlights the desperation for change. It seeks to promote action, of any kind, against the oppression of the Ottomans, and Nikolaos is nominated to seek change by communicating with European nations. The desperation of the Cypriot ‘noblemen’ and clergy that signed the letter is emphasised by the acceptance of military force if necessary.

Unfortunately, the letter’s conclusion and signatures are mostly illegible. The date is written in letters ‘αωκα’ with initials for the year 1821 and ‘ε’ the initial for 5. Under the date it refers to the ‘διασωζοντες’ (those that were saved). I believe that these are influential clergy, or men of means, who had avoided the death penalty when the Ottomans ordered the hanging of the Archbishop of Cyprus, Kyprianos, and 450 other influential Cypriot figures. There is also reference to ‘Ο εξ αοιδήμου αρχιεπισκόπου’ which signifies the one that is not forgotten, possibly referring to the recently executed Kyprianos.

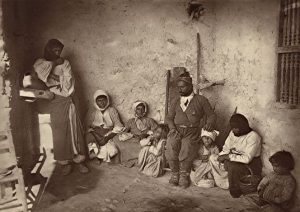

At the bottom of the letter there are monographs, stamps and signatures of the clergy and leading figures who support its cause. Further research can give us insight into these figures and their role in Cypriot history. The clearest signature of all is ‘David Antreadis of Limassol’ (second from the right). Among the others, the first part of the surname ‘xatzi’ can be distinguished from the symbol x with a cross on top.

It has been a challenge researching and deciphering the key points of such a fascinating letter. As a Greek Cypriot myself, I feel it is an invaluable source revealing a Greek Cypriot perspective during a critical time in Cypriot history.

This is a very interesting commentary by Vasiliki Vartholomaiou. I regret not having consulted this collection in the early 1980’s in Cambridge when I was writing upon my PhD – in anthropology, which may explain my missing it then. Could the word ‘diasozontes’ employed in this letter of appeal also mean ‘survivors’?