Sir George Biddell Airy: instrument making and engineering

A guest blog post by Daniel Belteki, University of Kent

Sir George Biddell Airy was the Astronomer Royal and the director of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich from 1835 to 1881. He is mostly remembered as an astronomer, mathematician, and one of the first public servants in charge of advising the government on matters of science and technology. However, another aspect of his genius was his talent as an engineer. Traces of Airy’s fascination with engineering and mechanics appear throughout his entire life. In his autobiography, Airy refers to making his first telescope while a schoolboy in Colchester, and during his early career in Cambridge he designed the Northumberland telescope as well as the dome of the Cambridge Observatory which was to house the instrument.[1] Illustrative of his knowledge in the field was also the number of government commissions related to engineering and mechanics for which he was asked to be a consultant: the Royal Commission on the Railway Gauge, the Tay Bridge disaster, the design of the Crystal Palace, the correction of compasses on iron ships, or the usefulness of the Charles Babbage’s difference engine, to mention just a few.

Airy maintained close friendships with engineers such as Isambard Kingdom Brunel and the Ransome family (manufacturer of agricultural equipment). In one of his letters to another engineer, Charles May (short-term partner in the Ransome family firm), Airy declared his admiration towards engineers: “Long live the Engineer, for they have more go in them than anybody else.”[2]

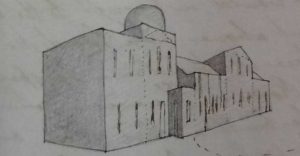

RGO 6/9/172 Drawing by George Airy of the Meridian Building at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, 1848

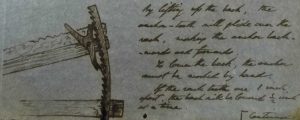

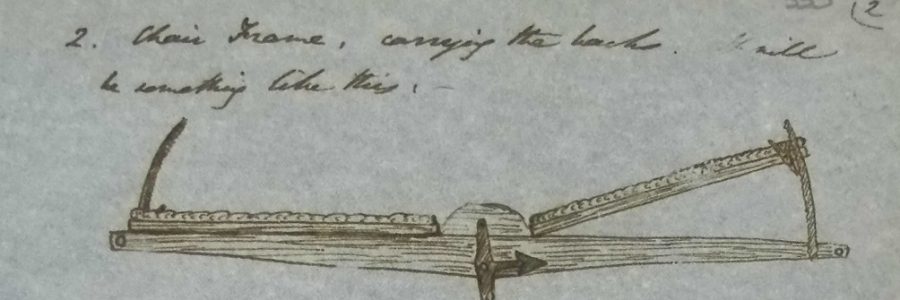

Airy similarly channelled his own engineering spirit in his correspondence with instrument makers. In one of his many letters to the optical and scientific instrument makers Troughton & Simms, he remarked that he hoped his requests to make customised parts (designed by Airy himself) for the various instruments of the Observatory had not yet driven the instrument makers insane.[3] In the same letter, Airy referred to the attached design as one of his many “humble contrivances”. Small drawings of these “humble contrivances” were quite often utilised by Airy in his correspondence with instrument makers, providing us with visual proof of his skill. At other times, similar visual clues were utilised in his letters to the carpenter of the Observatory, known as W. Green, who was in charge of making smaller items such as glass covers, frames, and boxes, but was also employed in constructing the observing chair for the Great Equatorial in 1859.[4]

While Airy’s fascination with engineering and mechanics is only one side of the nineteenth-century man of science that we have seen so far, the 12 cubic metres of archival material related to Airy’s life and work held at the Cambridge University Library still hide the various other sides of the man that remain to be explored.

***

A catalogue of the George Biddell Airy Papers is available on Janus. The papers can be accessed in the Manuscripts Reading Room.

Footnotes

[1] Airy, Wilfrid (ed.), Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy (Cambridge University Press, 1896), p. 30. For a drawing of the mounting of the Northumberland Equatorial object glass, see RGO 6/157: 271.

[2] See RGO 6/721: 526.

[3] Airy to James Simms, RGO 6/743: 1037.

[4] See for example, the letter at RGO 6/736: 334-335 in which Airy outlines his instructions to W. Green on the observing chair for the Great Equatorial of the Greenwich Observatory (another drawing of this is shown in the top image of this blog post).