Papers of a forgotten folklorist: Charles Dack

There is often more to the books in Cambridge University’s Rare Books Room than meets the eye, with many of them containing unique handwritten accessory material and ephemera such as newspaper cuttings, slim pamphlets and even advertisements. This post explores the surviving papers of a forgotten regional folklorist, Charles Dack, which found their way into the University Library as accessory material bound together with printed works. The ‘golden age’ of British folklore collection was inaugurated with the foundation of the Folklore Society in 1878 and ran up to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. Popular beliefs, customs and legends that a generation earlier had been despised by virtually all educated people and earmarked for eradication became a matter of intense interest to genteel amateurs during this period. A plethora of national, regional, county and even village collections of folklore poured from the presses, often locally or privately printed. Cambridge University Library has a fine collection of these sometimes ephemeral publications accessible in its Rare Books Room, with other folklore collections available on open shelves on North Front 2.

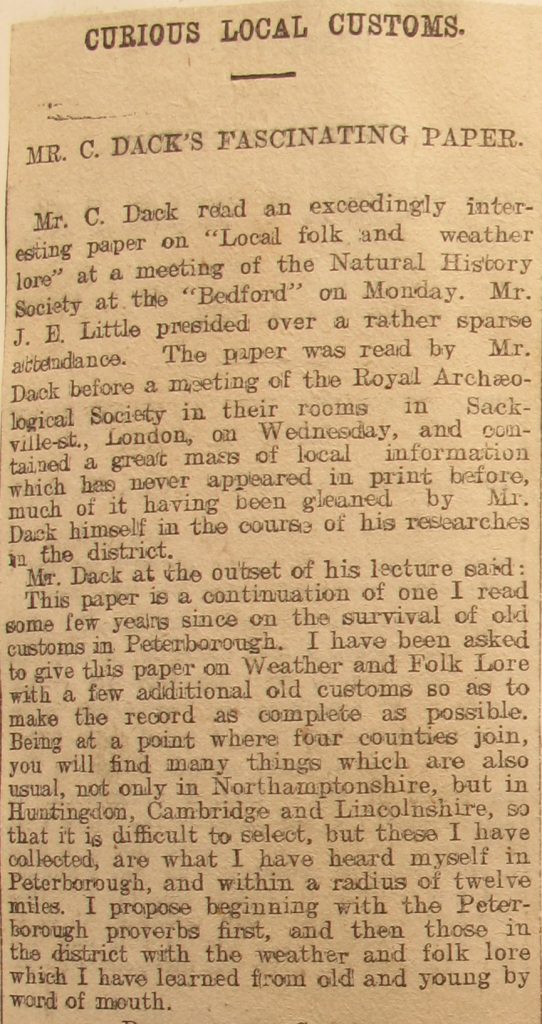

Some folklorists, however, were unable to bring all of their projects to fruition. One such individual was Charles Dack (b. 1847, d. after 1921), a clerk for the Great Eastern Railway based at Peterborough who was a keen amateur antiquary, organist, folklorist and an early honorary curator of Peterborough Museum. Dack was born at Holt in Norfolk but moved to Peterborough to work for the railway as a clerk at a young age. He became fascinated by the folklore of the region, and as curator of Peterborough Museum he had access to the manuscripts of the poet John Clare (1793–1864), who collected the folklore of his native village of Helpston (seven miles north of Peterborough) in the 1820s, before the word ‘folklore’ had even been coined. Dack also seems to have gained a great deal of local knowledge from talking to visitors to the museum.

In 1899 the Journal of the British Archaeological Association published an article by Dack, ‘Old Peterborough Customs and their Survival’, based on a talk he delivered to the Association, and in 1911 Dack brought out a short pamphlet entitled Weather and Folk Lore of Peterborough and District. However, Dack was without the financial backing to bring out a definitive study of the folklore of the Peterborough region, primarily because, as a railway clerk, he belonged to a lower social class than most amateur folklorists of the era. In 1921, perhaps after Dack’s death (although I have been unable to confirm Dack’s date of death), Cambridge University Library purchased Dack’s personal copies of his own writings on folklore from the bookseller Gustave David. These are now available in the Rare Books Room under the classmarks Lib.5.89.520 and 521, and include cuttings of articles on folklore written by Dack and others for local newspapers, as well as much handwritten accessory material by Dack that was never published in his lifetime.

Folklore was a popular subject for local newspapers in the late nineteenth-century, when there was a seemingly limitless fascination for a world that was fast disappearing. Peterborough, in particular, was transformed in the nineteenth century from England’s smallest cathedral city into a major junction on the main railway line between London and Edinburgh and an important centre of the vast Victorian brick-making industry. Many people were eager to cling to the security provided by old customs in the midst of such bewildering change. In 1889 the Soke of Peterborough became a county in its own right, separate from Northamptonshire, a status it would enjoy until 1965.

In addition to a particular interest in weather-lore, Dack collected calendar customs, superstitions about good and bad luck, civic customs, divination rites, and traditional songs. His major period of collection was in the 1890s, and since his informants were largely elderly people in their sixties or seventies he was often recording customs that died out in their childhood in the 1830s or ’40s. The information Dack preserved about the mummers’ plays of Peterborough and the surrounding villages is especially interesting to scholars of folk drama.

Although Dack published books on numismatics, Mary Queen of Scots, and the painter Thomas Worlidge, his writings on folklore remained largely unpublished beyond local newspapers. When I encountered this remarkable collection of accessory material, therefore, I decided to ‘complete’ Dack’s work by bringing the unpublished material to light in the first complete study of the folklore of the Peterborough region, Peterborough Folklore, which draws on the collections of John Clare and Charles Dack, as well as a great deal of other material. The book is intended to correct the anomaly that the Soke of Peterborough is one of very few English regions whose folklore has never been the subject of a dedicated regional study – partly because Dack never completed his work, and partly because Peterborough was absorbed into Cambridgeshire in the 1970s, leaving folklorists unsure about which county it should be included in.

Charles Dack remains an obscure figure; Peterborough Museum has no picture of him, although other early curators were honoured with portraits, nor does it possess any of his papers. It may well be that Cambridge University Library Lib.5.89.520 and 521 represent his only surviving manuscripts. Yet Dack deserves to be better known, not only for his work on the folklore of Peterborough but also because he was the first person to realise the importance of John Clare’s papers for the study of folklore.

Guest post by Dr Francis Young

Pingback: Publication of Peterborough Folklore | Francis Young