Living the Gothic Revival: William Burges and Tower House

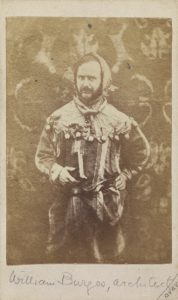

William Burges (1827-81) identified himself throughout his prolific career as an ‘art-architect’1. Richard Popplewell Pullan (1825-88) was also an artist and architect, and like Burges worked alongside Matthew Digby Wyatt for the Great Exhibition in 1851. Pullan married Burges’ sister Margaret in 1859. Burges’ career flourished through architectural commissions including Cork Cathedral and Cardiff Castle, domestic projects for the Yatman family and the Marquess of Bute including Knightshayes and Castell Coch, Trinity College in Hartford CT, as well as his oversight of the Medieval Court in the International Exhibition of 1862 at South Kensington. As his biographer J. Mordaunt-Crook has extensively explored, Burges became well known as a playful and innovative designer, from jewellery to monumental sacred and secular architecture, and both his wit and education across Classical and medieval history were often noted2. His sense of fun as well as his engagement with the Middle Ages is evident in projects such as his rock-crystal ewers and his 1860s portrait as a medieval jester in the National Portrait Gallery. Pullan’s work in this period, however, dwindled with little success in competitions or commissions and he was better known as a writer and antiquary than a designer. His main claim to fame was his discovery of the Lion of Knidos in Greece during an excavation in 1858. His published lectures on Christian architecture was also a popular seller for late Victorians captivated by the exponential rise of church buildings, particularly in the Gothic Revival style, across the nation and throughout the British Empire3.

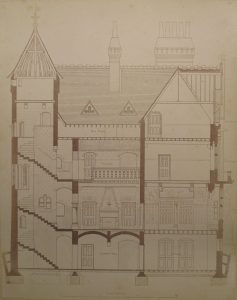

At the height of Burges’ success, he designed his own home on Melbury Road in Kensington, and titled it Tower House. Imposing, asymmetrical, and four storeys tall, the house is made of bright red brick with stone dressings, its prominent conical tower nestled between the two main wings of this compact yet stridently geometrical town house. The neighbourhood was a key site for artists in the late Victorian period, and his neighbours included the painters George Frederic Watts (known as ‘England’s Michelangelo’) and Frederic Leighton, who became President of the Royal Academy in 18774. Burges began designing the house in July 1875 and it was nearly complete by 18785. Each room was given a theme, and the most sumptuous room was not his own, but the guest bedroom.

Decanter made for James Nicholson, 1865-66. Burges designed two similar flasks for Tower House. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Attention to detail was paramount, connecting narratives and rich layers of symbolic language throughout the house, from the windows’ retelling of the medieval theme of ‘The Storming of the Castle of Love’ to hall mosaics depicting Theseus and the Minotaur. One of Burges’ primary beliefs was founded on the integration of art and architecture in order to express in new Victorian terms what the medieval imagination could do. In his 1865 lectures on Art Applied to Industry, Burges wrote, ‘Say we were in the royal palace of Westminster, we should find the ceiling boarded, with painting on it…But the great feature of our medieval chamber is the furniture; this in a rich apartment would be covered with paintings both ornaments and subjects; it not only did its duty as furniture but spoke and told a story’6. Mary Axon describes it as a place of ‘stories and patterns, gold and silver, stars, jewels, rich woods, mirrors, massive furniture, stained glass, marvellous and singular antiques and curios, and above all, colour. Visitors were frequently overawed by the splendour and dazzled by the profusion of colour and details, and by the fascinating mixture of history and fantasy. Tower House was designed to delight and amuse with its abundant glistening materials, display of luxury, and cultural references drawn from western and eastern sources, in which narratives from Dante mingled with myths and legends from diverse cultures as well as his own biographical details. Visitors to the house would be met by a mosaic on the floor which featured an image of Burges’ favourite poodle, Pinkie. A description of Burges’ own writing desk gives a flavour of his sense of humour and intelligent use of narrative in design: ‘Figure subjects within gilded frames illustrate the uses of writing. A young man kisses a love letter before posting it in a tree trunk, a merchant fills his ledger, an urchin learns to write, while his tutor, a monk, punishes him for his tardiness by pulling his ear, and an old man makes his will’8.

Tower House was widely reviewed and much discussed in the architectural press and in publications on Victorian domestic architecture and taste, both before and after Burges’ death. Axel Haig, Burges’ preferred draughtsman for numerous commissions and competitions, produced numerous detailed images of Tower House for a feature in The Architect in 18809. Even by Victorian Gothic Revival standards, the house was seen as both delightfully (and ostentatiously) sumptuous and fantastically opulent. The architectural and decorative arts writer Mrs Haweis referred to it as ‘Aladdin’s Palace’10. It is akin to John Soane’s house and Leighton’s house in its triple role as semi-public self-expression, domestic comfort and hospitality, and advertisement for the capacity of its designer-owners to create beautiful and striking art and architecture for established and new patrons. A monumental portfolio during Burges’ life, it therefore also lent itself well to becoming a book of descriptions and plates in Pullan’s The House of William Burges.

The Yatman Cabinet, designed by Burges for H.G. Yatman, with paintings by Edward John Poynter. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Following Burges’ death in 1881, Pullan published numerous books related to Burges’ designs and was also responsible for continuing some of the architectural office’s projects including Cardiff Castle. The goal was not only to preserve Burges’ memory and reverence his achievements, but also to keep the practice going. In his introduction to the 1883 publication Architectural Designs of William Burges ARA, Pullan explained that he desired the book to ‘afford evidence of Mr. Burges’ marvellous powers of adapting Gothic architecture to the requirements of everyday life without altering or degrading its characteristic features. It will tend also to exhibit his profound knowledge of style, his thorough acquaintance with iconography, the great versatility of his genius, and his great imaginative power …’11 Pullan inherited Tower House after Burges’ death, and so the publication of The House of William Burges, which first appeared as a series of plates with an introductory essay and room descriptions by Pullan in 1885, is as much a testament to Pullan’s interest in keeping Burges’ memory alive and living within the house as a responsible steward as it is a demonstration of Pullan’s own significance as a historian in his own right and as Burges’ friend and brother-in-law. The publication reminds its readers both of Burges’ design prowess and Pullan’s inheritance.

The 40 plates in the book begin with architectural plans, and proceed as a tour of the house. The first stop after passing through the entrance hall is the dining room, followed by the library and drawing room. These more public rooms on the ground floor are then left behind as the viewer climbs the staircase with its stained glass windows. The guest bedroom photographs emphasise the specific details and furniture of the interior: the decorated bed-head, the wardrobe, and the backs the shutters which would be seen when the guest would retire for bed. The furniture, because of Burges’ interest in medieval furniture and his commitment to the combination of allegory, historical sources, and the Gothic Revival, provides rooms within rooms, leading to miniature architectural fantasy worlds of their own.

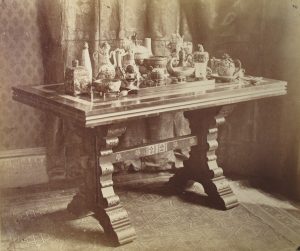

Burges’ own bedroom’s plates in The House of William Burges also alternate between furniture and interior decoration, including the bed, washstand, and ceiling paintings. Though Burges had no children, there were also day and night nursery rooms; the final plate is a table with a series of ornamental objects, concluding the tour with a range of microarchitectural items to emphasise the domesticity of the spaces, Burges as maker and collector, and the importance of taste not only in objects themselves but also in their presentation within an interior. In the context of this posthumous project, the relationship between the rooms and their collections of bespoke furniture and decorative objects constitute a double portrait of Burges as designer and host, and Pullan as curator, memorialiser, historic guest, and present host. It is both Burges and Pullan who present the house together.

The photographs of the interiors originate with Bedford Lemere’s work prior to Burges’ death, when he first photographed the house in 187812. However, the sequencing is Pullan’s decision, and the text for The House of William Burges is Pullan’s own. Pullan’s descriptions amplify the lively dynamism of Burges’ designs, bringing the photographs, the house, and the imagination of his brother-in-law to the fore. Plate 27, the chimneypiece in Burges’ bedroom, reads: ‘A graceful mermaid, arranging her long golden locks with the aid of a mirror, is the chief feature in this composition. Around her there are branches of coral, and above her there is a figure of an infant mermaid rising out of a shell. Skates and John Dorys in a turbulent sea form the frieze. All these are coloured after nature’13. The descriptions end with the final plate, of Burges’ table and ornaments. Pullan writes, ‘All these were frequently used by him, both at his chambers and in his house; for, as he was accustomed to say, “What is the object of having pretty things unless one makes use of them?”’14.

The University Library’s copy of The House of William Burges, apparently formerly owned by Evelyn Waugh, was acquired from Maggs Bros. in August 2016. It can be consulted in the Rare Books Room, and has the shelfmark Tab.b.936.

1 William Burges, Art Applied to Industry: A Series of Lectures, London, 1865

2 J. Mordaunt-Crook, William Burges and the High Victorian Dream, London, 2nd edn, Frances Lincoln, London, 2013.

3 Richard Popplewell Pullan, Elementary Lectures on Christian Architecture, London, 1879.

4 Caroline Dakers, The Holland Park Circle: Artists and Victorian Society, London and New Haven, 1999.

5 J. Mordaunt-Crook, Mary Axon and Virginia Glenn, The Strange Genius of William Burges ‘Art-Architect’, exh cat, National Museum of Wales, 1981, p. 58.

6 William Burges, Art Applied to Industry, London, 1865, p. 18.

7 Strange Genius, p. 58.

8 Mary Axon, ‘Escritoire’, in Strange Genius, p. 81.

9 ‘Tower House’, The Architect, xxiii, 1880, p. 314.

10 Mary Eliza Haweis, Beautiful Houses: Being a Description of Certain Well-Known Artistic Houses, London, 1889, p. 17.

11 Dakers, Holland Park Circle, p. 177.

12 The House of William Burges, plate 27.

13 The House of William Burges, plate 27.

Pingback: Waviana in the Book Trade | The Evelyn Waugh Society

What a shame this remarkable book can’t be more widely shared in digital form, but how grateful we are to Evelyn Waugh and Sir John Betjeman for ensuring Burges’ astounding genius was not lost!

The book IS available in digital form, can be found here: https://archive.org/details/HouseOfWilliamBurges_201504/mode/2up

Thank you for posting this link!