A chance discovery: Guest post by Jason Scott-Warren

One of the newest arrivals in the University Library’s Rare Books department was a chance find on Ebay. The History of Our B. Lady of Loreto (6000.e.154) is a translation by Thomas Price of a Latin work by the Italian Jesuit Orazio Torsellino, and was printed at the English College at St Omer in 1608. It told the miraculous tale of how the Virgin Mary’s house—a site of pilgrimage that had become increasingly inaccessible since the Holy Land had been overrun by ‘barbarians’—was transported by angels first to Dalmatia, and then to Loreto in central Italy. Much of the book is taken up with detailing the numerous miracles that have been procured by the aid of the Madonna of Loreto, ‘in so much that there is none (though desperat & wicked) but if he visit the house of Loreto may not easily perceive almightie God to be present with his B[lessed] Mother, in his Mothers litle House’. Torsellino’s work was thus a counter-strike against the Protestants who had poured scorn on Catholic shrines, offering plentiful documentary evidence for their efficacy.

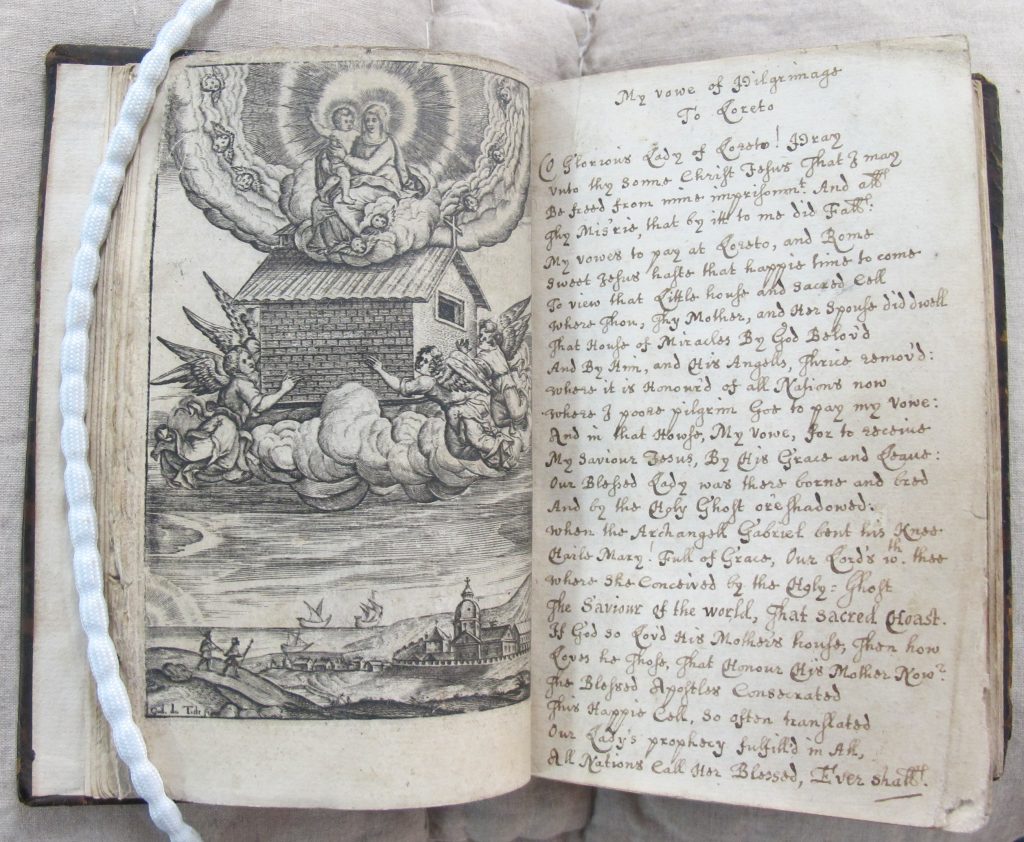

The author’s promise to go on pilgrimage to Loreto, facing an image of the Blessed Virgin with the Holy House where she was born, miraculously flying to Loreto.

The remarkable feature of this copy is a set of five unrecorded poems, penned in a tiny but very clear hand on two sets of leaves that have been bound into the book just before the Preface at the front and the Index at the back. We begin with ‘My vow of Pilgrimage to Loreto and Rome’, in which the speaker asks to be ‘be freed from mine imprisonment’ so that he or she might undertake a pilgrimage to Italy to see the Virgin’s house and St Peter’s chair. Then follows ‘My Presents in prison / On The Epiphanie’, which offers Jesus charity, prayer, and mortification, the spiritual equivalents of gold, frankincense and myrrh. The final poem at the front of the book is ‘My Vowe to St Winifride’s / perform’d & obtain’d’, which celebrates the holy site of St Winifred’s Well, in Flintshire, where ‘Thousands of Lame, deafe, dumbe, & blinde’ have been cured. The author shivers at the memory of a visit to the waters: ‘A wonder ’tis to me it kills not many, / Soe peircing cold it is’. And yet the well has cured old people, sick babies and barren women: ‘O Blessed place! where Faith is still encreas’d / In such as thought that Miracles were ceas’d’.

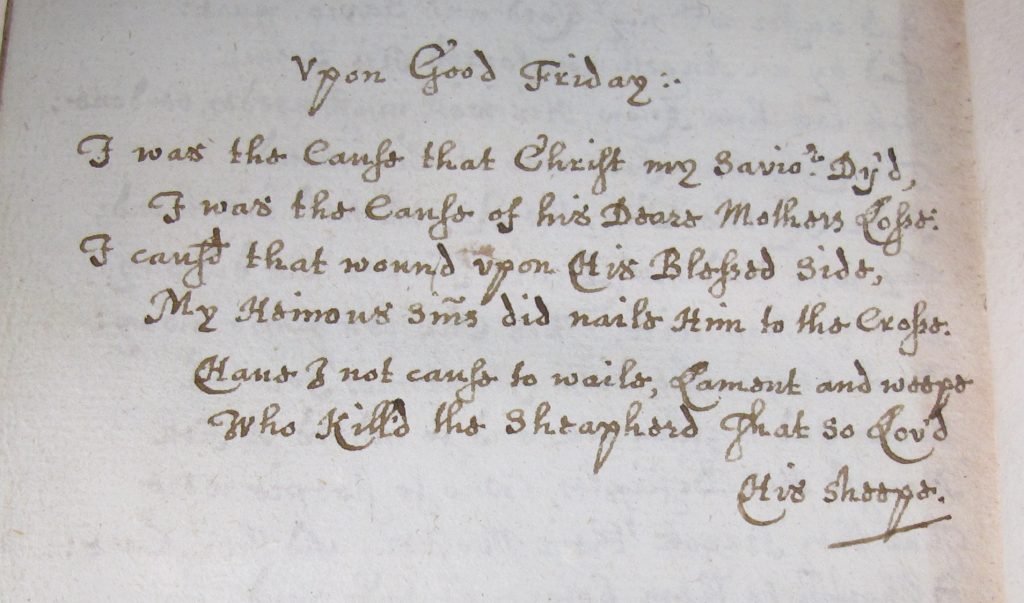

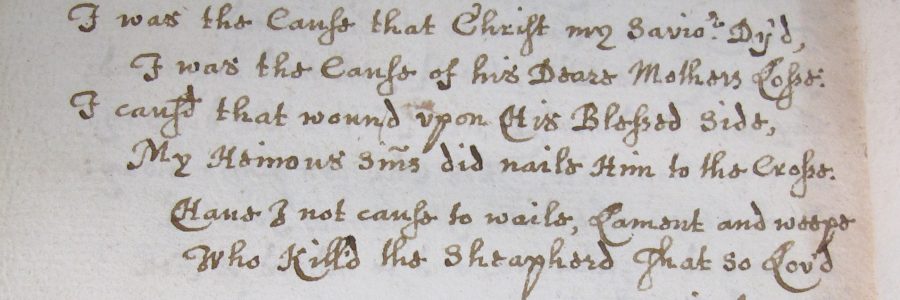

At the other end of the book there are two more poems. The first is an intense meditation ‘On that part of our Saviours passion / in the Garden’. Contemplating the sufferings of Christ, the poet urges himself to weep: ‘salt teares in showres then from thine eyes lett Fall, / Mourne ev’ry day a part’. The second is a short coda, ‘Upon Good Friday’:

I was the Cause that Christ my Saviour Dy’d,

I was the Cause of his Deare Mothers Losse.

I causd that wound upon His Blessed side,

My Heinous sinns did naile Him to the Crosse.

Have I not cause to waile, Lament and weepe

Who Kill’d the Sheapherd That so Lov’d His sheepe?

The poem lays the blame for the crucifixion firmly at the door of the individual sinner, and again the result is tears—wailing, lamenting, weeping.

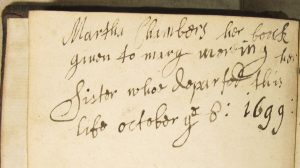

For all the first-person directness of these poems, though, we have no idea who wrote them. The book has a mark of ownership on a front flyleaf: ‘Martha Chambers her boock / giuen to mary mereing her / Sister whoe departed this / life October the 8: 1699:’ But the scruffy hand that pens this inscription is not the same as the hand that transcribes the poems. The poems do drop one clue as to the date of their composition, when the poet yearns to visit Rome to ‘see St Peters chaire / And Honour God in Alexander there’. The reference here is presumably to Alexander VII, who was Pope from 1655 to 1667. Beyond that, we have the fact of the writer’s imprisonment, and the evidence of their handwriting, but the question of their identity is likely to remain a puzzle. In the meantime, the book is a fascinating testimony to English Catholic devotion, and another example of how creative early modern readers could be in combining manuscript and print for their own ends.

Guest post by Dr Jason Scott-Warren