Henry Bradshaw and the Foundations of Codicology

In 2015, the Sandars Reader in Bibliography was Richard Beadle, Professor of Medieval English Literature and Palaeography at the Faculty of English. The subject of his three lectures was the life and work of a scholar who was instrumental in the formation of many of the key principles and practices that underpin modern analytical study of the physical make-up of medieval books. It is a source of considerable, though we hope not immodest, institutional pride that this man was one of the Library’s own. Henry Bradshaw was first employed at the University Library as Principal Assistant in November 1856. After a brief, nine-month spell away from the Library, he returned in 1859 to work in an untitled capacity with the medieval manuscripts and rare printed books. He was appointed University Librarian in 1867, in which post he served until his premature death in 1886, aged 55.

Henry Bradshaw and the Foundations of Codicology brought together entertaining and informative details from the subject’s personal and professional lives, from his correspondence or from his (often overlooked) papers and notebooks at the University Library, and from the traces left in manuscripts here and in other collections, in order to make three important contributions to our understanding of Bradshaw’s work. For anyone who missed the public lectures, we are delighted to announce that illustrated copies are now available to purchase from the author (details below).

In the first lecture, ‘The Bibliographer as Sleuth’, Professor Beadle proposed an alternative interpretative framework for study of Henry Bradshaw’s scholarship. Bradshaw himself described his bibliographical labours as following ‘the natural history method’, likening his methodical, taxonomic work on books to that of contemporary scientists; and, indeed, scholars have tended to take him at his word, describing him as a ‘scientific bibliographer’. In his own sleuth-like way, Professor Beadle pointed instead to minor, but telling evidence or incidents in Bradshaw’s life – his narrow escape from being shot and the search for evidence to identify the culprit, his identification of a travelling companion’s hotel room by the boots left outside the door, his passion for the emerging genre of detective fiction – that exemplify his subject’s ‘detective-like powers of observation’.

It is these powers, and how they were brought to bear upon the study of medieval books, that was the subject of Professor Beadle’s second lecture, ‘Bradshaw’s Methods’. The title echoes that of Paul Needham’s 1988 Hanes Lecture and subsequent pamphlet The Bradshaw Method. While Professor Needham’s focus was primarily upon Bradshaw’s work on incunabula – books printed prior to 1500 – and specifically their collation, Professor Beadle redressed that balance by concentrating on manuscripts and the ‘whole arsenal’ of methods at his disposal, to which Professor Needham had only briefly alluded.

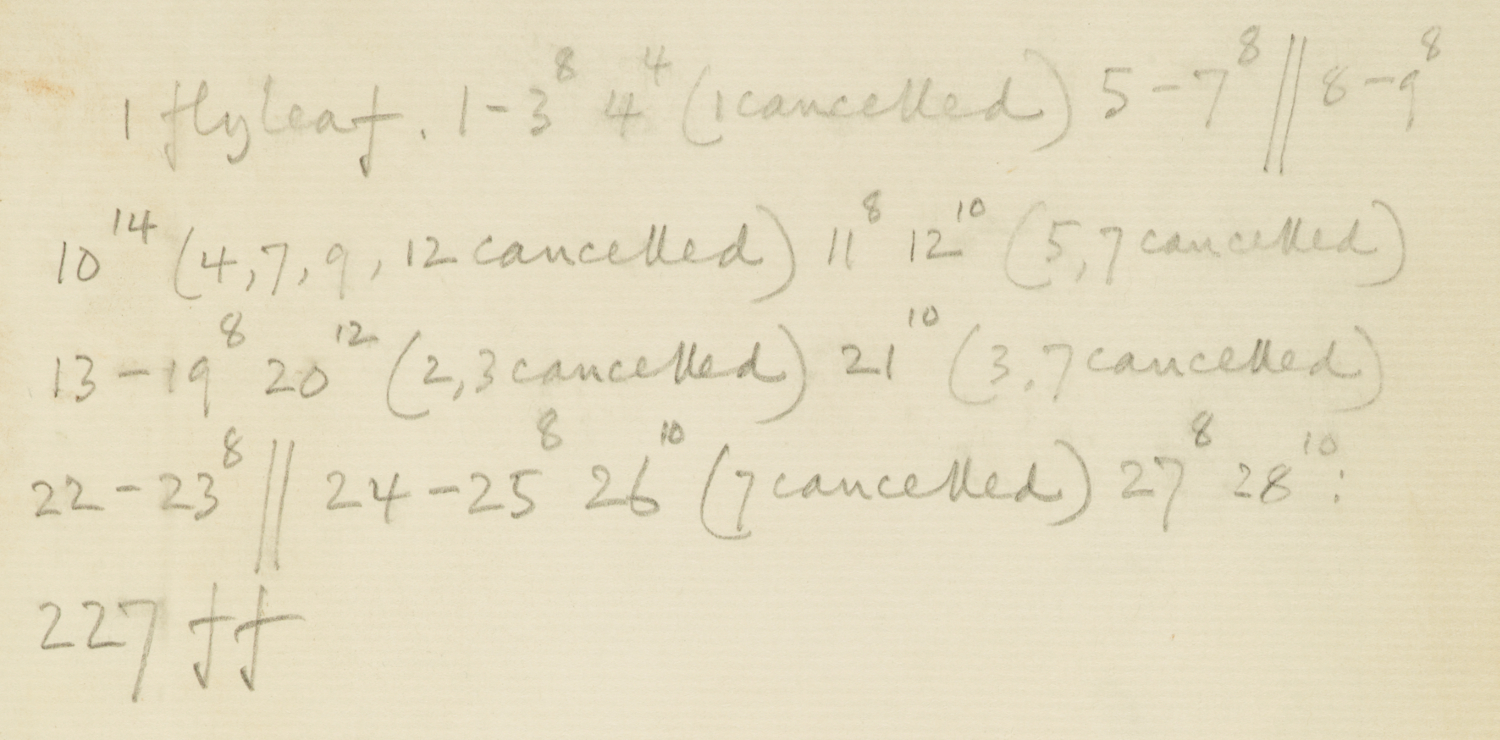

Against the backdrop of what to modern sensibilities seems an alarming enthusiasm for dismantling medieval codices on the part of Bradshaw, Professor Beadle traced his formulation of a range of codicological approaches through his notebooks and scribblings in medieval manuscripts at the University Library and King’s College: collation diagrams, observation of watermarks, crafting of working models, noting the middle of quires or writing out collation formulae on endleaves or pastedowns.

Whether found in his private correspondence, personal notebooks, or posthumously published papers, or on the pastedowns of the manuscripts to which they pertain, these ‘Bradshaw’s Guides’ amounted in many instances to introductions to what their creator termed a book’s ‘personal history’. Though not as widely circulated nor as readily available as the eponymous compilation of railway timetables of George Bradshaw (no relation), to which the title of Professor Beadle’s third lecture surely alludes, nevertheless these aids to navigating the medieval book formed the practical basis for Henry Bradshaw’s thoughts about the discipline of codicology avant la lettre and its connection to the Handschriftenkunde of contemporary bibliographical scholarship in Germany. While Bradshaw never published a textbook, Professor Beadle highlighted the many instances in which his subject articulated the purposes and principles of codicology to the scholars with whom he so generously shared his expertise.

… ‘The Early Collection of Canons known as the Hiberniensis’ (1893), pp. 43-44 (UL, Rare Books, Cam.c.893.7)

Furthermore, Professor Beadle noted that shortly before his death Bradshaw was in fact preparing an explanation for publication, which appeared as an 1893 pendant to the Collected Papers of 1889, edited by his successor-but-one as University Librarian, Francis Jenkinson. Had his life not been cut short by a heart attack, Bradshaw might have received greater recognition from those scholars who adopted his descriptive technique of collation apparently without published acknowledgement: John Young and P. Henderson Aitken, W.W. Greg, E.A. Lowe and N.R. Ker, among others. While the nature of Bradshaw’s literary remains might tend to a rather fragmentary picture of his scholarly activities, Professor Beadle concluded his lectures with an in-depth examination of Bradshaw’s influence upon M.R. James’s descriptive catalogue of the manuscripts of King’s College, with particular reference to the description of King’s MS 3, ‘a curiously disorganised copy of St Augustine’s De quantitate animae’ from the second half of the 12th century. It is through the expertise and methods recorded here and duly acknowledged by James, Professor Beadle argued, that Bradshaw’s scholarly legacy was disseminated to future generations.

Copies of Richard Beadle’s 2015 Sandars Lectures, Henry Bradshaw and the Foundations of Codicology may be obtained from the author for £12.50, incl. postage and packaging. Please address enquiries to him at St. John’s College, Cambridge, CB2 1TP or rb243@cam.ac.uk