Puzzling Scribes and Medieval Puzzles: Guest post by Dr Eleanor Jackson

Note: readers of this post may be interested to learn that, since its publication, MS Gg.5.35 has been digitised in full and the images are now available to view, accompanied by detailed descriptive metadata, on the Cambridge Digital Library (25 February 2020).

To borrow a medieval book metaphor, CUL MS Gg.5.35 is a literary chest of treasures. This eleventh-century Anglo-Saxon manuscript contains a vast collection of Latin poetry from the Early Christian, Carolingian, and Anglo-Saxon periods. Yet among its many engrossing text pages, one portion of the manuscript stands out for its visual splendour—fols 209-262r, a cycle of picture poems (carmina figurata) known as In honorem sanctae crucis, composed by Hrabanus Maurus in 810-814. While these poems are found in numerous manuscripts, including another in Cambridge (Trinity College, MS B.16.3), their occurrence in Gg.5.35 raises particular questions about the use of this text in late Anglo-Saxon educational practices.

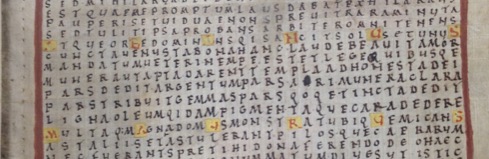

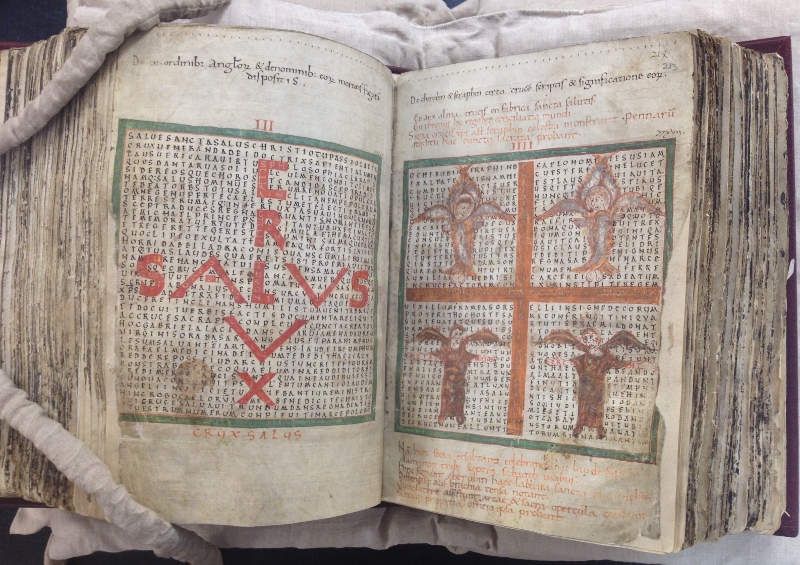

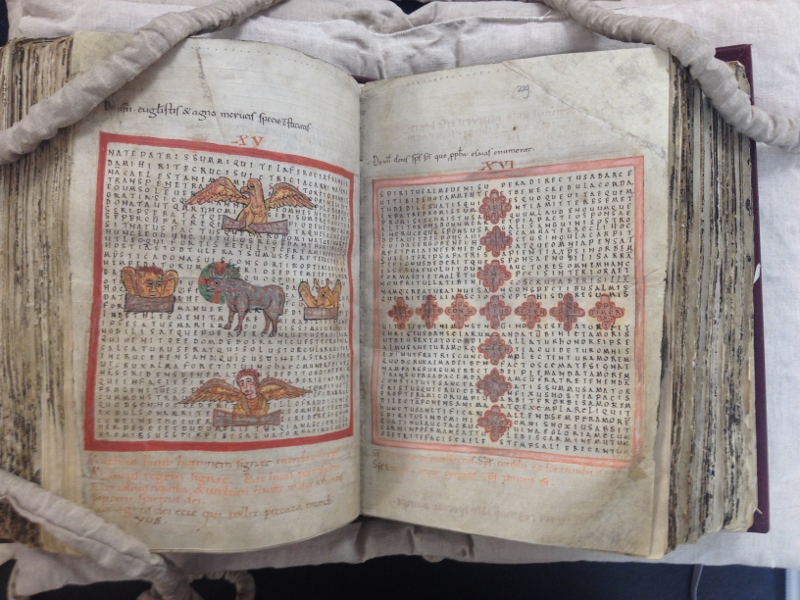

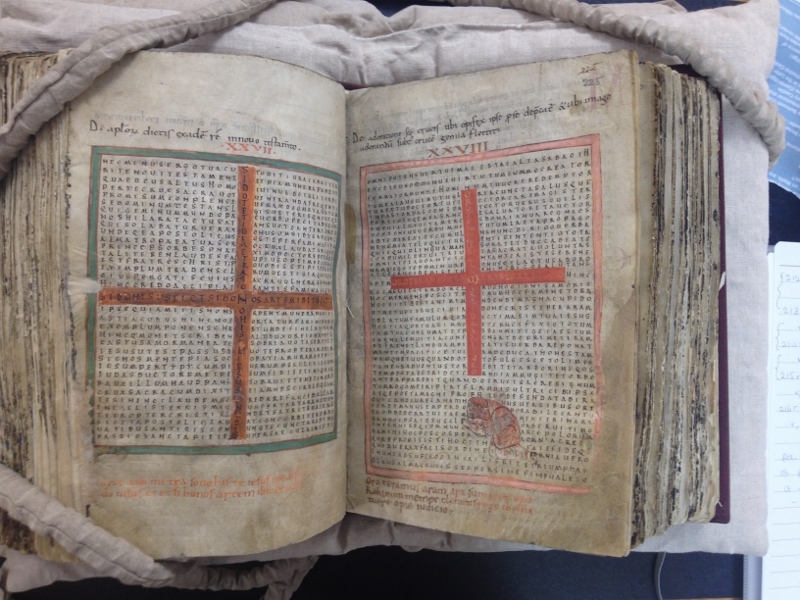

Each of the twenty-eight picture poems that form In honorem sanctae crucis explores a different theme relating to the Cross through a complex interplay of word and image. The poems each have an equal number of letters per line, written continuously like a grid. By following the letters in the usual direction for a Latin text—from left to right, top to bottom—each grid reads as one long poem. But within each grid, certain letters are also marked out with colour and drawings to form pictures. The letters that make up these pictures read as separate short poems embedded within the larger poem. As such, each page of In honorem sanctae crucis presents a puzzle of words and pictures, full of hidden and interrelated messages for the reader to decode.

However, the copy of In honorem sanctae crucis in Gg.5.35 differs from every other surviving version in one significant way. As well as the picture poems themselves, Hrabanus Maurus also composed prose commentaries which explain how to read the poems and elaborate on their meanings. In all other manuscript copies, each picture poem is placed on the verso (left-hand page) of an opening with the accompanying commentary positioned on the facing recto (right-hand page), so that the reader can easily examine the poem and follow along with the commentary at the same time (as in the Trinity copy, for example). But the creator of Gg.5.35 decided to adopt an entirely different format—they grouped all the picture poems together on facing pages (fols 211r-225r), followed by the commentaries in a single block at the end (fols 225v-262r).

Noting that this modification seems to undermine proper understanding of the poems, the scholar William Schipper described Gg.5.35 as containing ‘a confusing and misleading copy’ of In honorem sanctae crucis, and concluded that its compiler was perhaps less concerned with the meanings of the poems than with their decorative value as a set of pictures. The altered format certainly changes the reader’s experience of the text in a fundamental way, but could the compiler have had alternative motives that were more sensitive to the meaning of the poems and the anticipated needs of the reader?

One effect that the rearrangement has on the reader’s reception of the poems is that it requires them to work harder to uncover the meanings. Like a puzzle book with the answers at the end, the format adopted in Gg.5.35 excludes the explanations from the reader’s immediate field of view. This encourages them not to rely on the commentaries for the solutions, but to deduce them for themselves through looking and reading.

It may be significant that, based on the selection of texts included in the manuscript as well as its many explanatory glosses (annotations), the scholars A.G. Rigg and Gernot Wieland suggested that Gg.5.35 might have been made as classroom book. Perhaps relocating the commentaries to the end of the poem cycle was intended to adapt them for educational use, withholding the answers to encourage classroom dialogue and challenge the students’ interpretative skills. This possibility is reinforced by the considerable number of Latin riddles (enigmata) contained elsewhere in the manuscript—another form of poetic puzzle designed to improve students’ Latin and teach them figurative thinking.

Yet the displacement of the commentary texts to the end of the poem cycle in Gg.5.35 has another effect on the way that the reader experiences the picture poems—it focuses greater attention on visual interpretation, and especially on visual comparison. Whereas the layout of other manuscript copies encourages readers to draw connections between the picture poems and their facing texts, the layout of Gg.5.35 invites them to explore the new possibilities for meaning created by confronting picture poem with picture poem. That the compiler was conscious of this feature is demonstrated by their tendency to match the colour schemes of picture poems on facing pages, thereby increasing their diptych-like appearance.

Presenting the picture poems as an unbroken series in this way emphasises the cycle’s repetition and variation of geometrical shapes, colours, and letters, centred around the ever-present and ever-morphing form of the Cross. As the reader turns the pages, the coming together of the designs and the emergence of new ones seems to enact the core message of Hrabanus’ work—that the Cross is infinitely meaningful and the centre of all existence.

In some cases, the symbolism may be more specific, as on fols 221v and 222r where the image of Christ ‘spreading his arms in the manner of the Cross’ faces the image of the cross inside the square, ‘containing all things’. As the pages turn, the letter ‘O’ which represents Christ’s navel lines up perfectly with the letter ‘O’ at the centre of ‘all things’. In this way, the reader maps Christ’s body onto the universe, in line with the medieval tradition of incorporating Christ’s body into world maps with his navel forming Jerusalem, believed to be its geographic and spiritual centre.

Far from suggesting a context in which meaning was undervalued, Gg.5.35’s rearrangement of In honorem sanctae crucis should therefore be understood as opening up new possibilities for reception. Indeed, it seems that this copy is uniquely adapted for teaching students to approach theological concepts through visual and textual analysis. True to Hrabanus’ original intentions, Gg.5.35 demonstrates the medieval fascination with the visual forms of words and the textual dimension of images, with puzzling out meanings and revelling in ambiguities. As Hrabanus himself phrased it:

The fingers rejoice in writing, the eyes in seeing,

and the mind at examining the meaning of God’s mystical words.

(Nam digiti scripto laetantur, lumina visu / Mens volvet sensu mystica verba dei).

Dr Eleanor Jackson

Bibliography

- Peter Godman, Poetry of the Carolingian Renaissance (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985), 249.

- A. G. Rigg and G. R. Wieland, ‘A Canterbury Classbook of the Mid-eleventh Century (the “Cambridge Songs” Manuscript)’, Anglo-Saxon England 4 (1974), 113-30.

- William Schipper, ‘Hrabanus Maurus in Anglo-Saxon England: In Honorem Sanctae Crucis’, in Early Medieval Studies in Memory of Patrick Wormald, ed. Stephen Baxter, Catherine Karkov, Janet L. Nelson, David Pelteret (Farnham, Surrey; Burlington, Vt.: Ashgate, 2009), 283-98.

Hi Dr Jackson,

How would we contact you with further questions regarding this piece?

Dear Francis,

Dr Eleanor Jackson is now working at the British Library as Curator of Illuminated Manuscripts. If you contact the Manuscripts Enquiries team via the form found on the following web-page, they should be able to pass on your questions to her: https://www.bl.uk/help/reference-enquiry-team

Please accept my apologies for the delay in responding to your enquiry. I was unaware that comments had been made on this blog post until one of my colleagues drew my attention to the backlog!

Best wishes,

Dr James Freeman

Medieval Manuscripts Specialist

Great Piece of literature indeed. i have never heard about the picture poems. It is very rejoicing to read about it in your post.