From Flat Plains to Ascending Hills: Conservation challenges for the Greenough Map

By Lucy Cheng and Ngaio Vince-Dewerse

Ever wanted to go behind the scenes to get a glimpse of how an exhibition is put together? The topic in itself is broad and complex. Every year, the Conservation and Collection Care Department at the Cambridge University Library (CUL) mounts two major exhibitions in the Exhibition Centre, twelve exhibitions in the Entrance Hall, and a myriad of pop-up exhibitions throughout the library. The materials we deal with ranges from rare books to ancient parchment manuscripts to very large maps, with the occasional ostrich feather and ectoplasm thrown in. In this blog, we would like to describe how we supported the largest object ever to be put on display in the CUL.

Ever wanted to go behind the scenes to get a glimpse of how an exhibition is put together? The topic in itself is broad and complex. Every year, the Conservation and Collection Care Department at the Cambridge University Library (CUL) mounts two major exhibitions in the Exhibition Centre, twelve exhibitions in the Entrance Hall, and a myriad of pop-up exhibitions throughout the library. The materials we deal with ranges from rare books to ancient parchment manuscripts to very large maps, with the occasional ostrich feather and ectoplasm thrown in. In this blog, we would like to describe how we supported the largest object ever to be put on display in the CUL.

But first things first. What do we do when we first see the objects that we need to put on display?

- We assess objects for their suitability for the exhibition, identify vulnerabilities, and make decisions in regard to whether items could withstand the handling. required during preparation and the pressure exerted on the object during display.

- We repair the objects where necessary to prevent damage during this process.

- We construct exhibition supports out of card, mount board, Perspex, and an array of other materials, all tested to make sure they do not give off any harmful substances that may damage objects, even if the damage isn’t immediately visible. We manipulate the material to support the objects in an unobtrusive, attractive, and safe manner.

- We negotiate with curators and our Exhibition Programme Manager to make sure their vision for the exhibition is realised and that items from our collection reach a wider audience with minimal disturbance to the objects themselves.

There were three requirements set out for the Greenough Map by our Curator, Allison Ksiazkizwicz, and our Exhibitions Programme Manager, Chris Burgess.

There were three requirements set out for the Greenough Map by our Curator, Allison Ksiazkizwicz, and our Exhibitions Programme Manager, Chris Burgess.

- The map needed to be the first object that the visitors see in the Exhibition Centre. In other words, it was to be the ‘star attraction’.

- It needed to be displayed vertically or as vertically as possible.

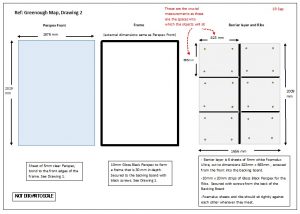

- The six parts of the map needed to be displayed together, in their intended positions, while making clear to the viewers that they are separate pieces.

So how does one make a flat map stand up? There are some obvious problems to tackle.

First of all, the large scale of the object. With the 6 maps laid out in position, the area measured more than two metres lengthwise and more than a metre and a half across. To start considering the whole object and for every subsequent planning meeting, it was necessary to de-camp to our Map Reading Room and climb on top of a movable ladder.

Our second and perhaps biggest problem was gravity. The most comfortable position for flat objects, including maps, is to lay flat. However, to maximise its visual impact, we have decided to display this map nearly upright.

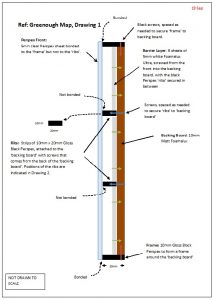

Various designs for the support and enclosure were considered before we settled on this one:

Without going into too much detail, over the course of several months, the design for the necessary ‘frame’ to protect and support this object morphed and morphed again through various manifestations. The changes were necessary sometimes due to the prohibitive cost or unavailability of a product, sometimes due to the physical limitations of a material chosen, and other times due to a need to simplify the process so we could achieve the task within a reasonable timeframe. What resulted is a complex structure that, when taken down to its parts, consists of 25 separate pieces that we assembled into a cohesive whole.

As with many things, obstacles led to innovations.

For the mounting of the maps on their backing boards we initially planned to employ a common method of mounting flat works in which very small pieces of Japanese paper are adhered to the back of an object with a tiny amount of reversible adhesive, such as wheat starch paste. These are then used to hinge the object onto an archival backing. As these maps are lined with linen we were not confident, however, that the wheat starch paste would stick well enough to the textile to give the objects the support they needed. We therefore needed to look elsewhere for a solution. This we found in the use of rare-earth magnets.

For the mounting of the maps on their backing boards we initially planned to employ a common method of mounting flat works in which very small pieces of Japanese paper are adhered to the back of an object with a tiny amount of reversible adhesive, such as wheat starch paste. These are then used to hinge the object onto an archival backing. As these maps are lined with linen we were not confident, however, that the wheat starch paste would stick well enough to the textile to give the objects the support they needed. We therefore needed to look elsewhere for a solution. This we found in the use of rare-earth magnets. These magnets are very strong for their size, are inert, require no adhesive and made the mounting relatively simple and straight forward, with minimal intervention or manipulation of the maps themselves. We covered them with dark blue paper, with a Japanese paper barrier between magnet and map, and, when placed on the blue border, they provided an unobtrusive but strong support.

These magnets are very strong for their size, are inert, require no adhesive and made the mounting relatively simple and straight forward, with minimal intervention or manipulation of the maps themselves. We covered them with dark blue paper, with a Japanese paper barrier between magnet and map, and, when placed on the blue border, they provided an unobtrusive but strong support.

The success of the project would not have been possible without the help of:

- Our colleague, Rebecca Goldie, who was at the start of this project with us

- Mark Bendall and his team at Engineering and Design Plastics Ltd, who have taken our design and gave it its physical form

- Our colleague, Peter Matlock, who made the crucial back support so our ‘frame’ could be supported at the desirable angle

- Our colleague, Deborah Farndell, who suggested the use of rare-earth magnets

- Our colleague, Sharon Catlin, who carefully cleaned the maps prior to installation and covered 48 little magnets in paper

- Our colleagues, Bryan Deighton and Samuel Foley, who helped us shift the heavy ‘frame’ at least a dozen times during the installation process

- Our curator Allison Ksiazkizwicz and Exhibition Programme Manager Chris Burgess, who set out the challenge in the first place

The exhibition in which the mounted Greenough Map is on display will run until the 29th of March 2018 in the Exhibition Centre at the Cambridge University Library.

Another great project brought to the public. Congratulations and thanks. Regrettably, from Australia, we can’t be there. Reading this article enables us to get closer though. Thanks.