Smelly Remedy: Womb Fumigation Illustrated in Seventeenth Century Print

Swelling, shifting and releasing noxious vapours, the Early Modern womb was deemed to be an unruly organ and the cause of numerous ailments. The symptoms provoked by the womb included, but were not limited to, a feeling of choking, laughter or weeping, and fainting or falling unconscious, sometimes for up to seven days.[1]

To quell the wild womb, women were recommended to receive an aromatic fumigation between the legs, while placing rank substances such as bitumen under the nostrils.[2] This was because the womb was considered to behave like a second nose, where it was attracted to pleasant smells and repulsed by stinking substances. By wafting fragrant aromas such as cinnamon and cloves from beneath, it could be coaxed back to its ‘natural place’.[3]

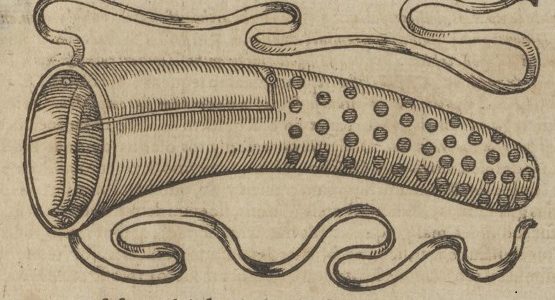

Peter Uffenbach, Ambroise Paré, and Conrad Gessner, Thesaurus chirurgiae, Frankfurt: Jacob Fischer for Nikolaus Hoffmann, 1610. K.7.31 (p. 531).

The apparatus necessary for a fumigation are illustrated in a book by the barber surgeon Ambroise Paré (1510–1590). The incense burner, pictured at the bottom of the page, has received a smouldering troche of aromatic spices. A bouquet of undulating lines flows from the tip of the burner’s funnel, showing the concentration of perfumed wisps that will be directed to the womb. The woodcut above the burner depicts the instrument that keeps an open passage to the womb for so-called noxious uterine vapours to be expelled, and medicinal aromas to enter. The length of ribbon is strapped to a girdle around the waist which secures the instrument in place.

These curious diagrams are on view in the Entrance Hall of the University Library as part of the exhibition Smelly Remedy: Womb Fumigation Illustrated in Seventeenth Century Print, on display until 31 March. The University Library’s collection holds intriguing illustrations of the ingredients necessary for womb fumigation, and also remarkably, prints of womb fumigation in action.

Aphra Behn (att. to) and John Harvey (ed.), after H. Sweerts (pseud. of H. de Vrye), The Ten Pleasures of Marriage and the Second Part the Confession of the Married Couple (1682), London: John Harvey, 1933 (facsimile). S727.d.93.26 (opp. p. 45).

The printing press generated illustrations of womb fumigation that could be circulated to a wide audience,[4] some of which can be found in emblem books and satirical literature. In this print, for instance, a midwife gets to work fumigating the patient by placing a stove at her feet. Smoke belches from the patient’s skirt for humorous effect, and in the background, a physician inspects a bottle of the patient’s urine to make further diagnoses.

The print originally came from a Dutch satire which was then translated into English by, it is believed, Aphra Behn (1640–1689), one of the few known women Restoration writers.[5] The book gives an account of the ten ‘pleasures’ of a newlyweds’ marriage, and as the chapters unfold, their relationship becomes more hopeless. After only three months, the new wife grows impatient, questioning why she has not yet fallen pregnant. An intensive medical regimen ensues:

with smearing, anointing, chafing, infusing … the good woman is to be made fresh and fit; but they make the bed and whole house so full of stink and vapour, that it may be said they rather stop the good and wholesome pores and other parts of the body….[6]

The treatment is used to such excess that the couple’s entire home is now fumigated. The medicine has not only reached the womb, but other parts of the body, causing more harm than good.

The prospect of being inspected by a male physician must have been extremely humiliating, especially for young women who were considered to be prone to womb troubles.[7] Yet fumigation was the most dignified of remedies, as a woman’s skirt not only sealed off the fumigation, but also hid this intimate activity. Paré actually comments on this, as he says that, ‘fumigations of aromatick things are more meet for maids, because they are bashfull and shamefac’d’.[8]

The book illustration is a testament to how commonplace and apparently quotidian the procedure was in the last third of the seventeenth century. The door in the background has been boldly left open so that a gaggle of gossiping women have every chance of peering in. The illustration is a fascinating source that demonstrates the setup of a womb fumigation, but it also suggests that by the 1670s, it could be the butt of a satirical joke.

This is just one example from the University Library’s collection that has offered a valuable opportunity to explore the visual sources that testify to the practice of womb fumigation in the seventeenth century. It has also offered some nuance by articulating a range of ideas about the procedure: womb fumigation could be moralised, as illustrated in an emblem book; satirised, as demonstrated in the Ten Pleasures of Marriage; or bare symbolic meaning, as demonstrated by the fluttering sheets of an anatomical pop-up book. Smelly Remedy reveals that the imagery of womb fumigation extends far beyond the diagrammatic illustrations confined in medical handbooks; instead, womb fumigation was represented in a range of contexts that voiced the beliefs and preoccupations that governed the Early Modern woman’s health and wellbeing.

Guest post by Lizzie Marx, Department of History of Art.

Lizzie’s exhibition Smelly Remedy: Womb Fumigation Illustrated in Seventeenth Century Print was awarded the Jean Michel Massing Curatorial Prize and will run in the UL Entrance Hall until Saturday 31 March. A video introduction to the exhibition is available and a virtual exhibition is accessible on the Library’s exhibitions webpage.

[1] A. Paré and T. Johnson (trans.), The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, London, Richard Cotes, 1649, pp. 633, 636.

[2] Ibid., p. 636.

[3] Helen King deals with this topic. See H. King, ‘Once Upon a Text: Hysteria from Hippocrates’, in S. L. Gilman, H. King, R. Porter, G. S. Rousseau and E. Showalter, Hysteria Beyond Freud, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1993, esp. pp. 21–22.

[4] M. H. Green, Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of the Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 245, 247–8, 265–67.

[5] H. Sweerts (pseud. of H. de Vrye), De tien vermakelikheden des Houwelyks, Amsterdam, 1678; H. de Vrye, A. Behn (trans. att. to) and J. Harvey (ed.), The Ten Pleasures of Marriage and the Second Part the Confession of the Married Couple (1682), London, John Harvey, 1933, pp. xiv–xv.

[6] A. Behn (as in n. 5), pp. 53–54.

[7] For an account of a woman’s humiliating inspection by a male physician, see E. Jorden, A Briefe Discourse of a Disease Called the Suffocation of the Mother, London, John Windet, 1603, pp. 25–26.

[8] A. Paré (as in n. 1), p. 639.