LGBT History Month at the UL

During February the University Library joined with a number of colleges and other institutions across town and University to mark LGBT History Month, an annual event promoting equality and diversity by increasing the visibility of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people and raising awareness of matters affecting the LGBT+ community. This began on 1st February with the raising of the rainbow flag (for forty years a symbol of gay pride) over the Library’s iconic tower and concluded on 28th February with a drop-in exhibition—entitled ‘Queering the UL’—of LGBT+ material from our historic and modern collections, an event which will be repeated tomorrow (Tuesday 20th March, 12.00-2.00, in the Milstein Seminar Rooms).

Whilst the display naturally includes material by or about individuals who lived, for example, as gay men (Oscar Wilde and Edward Carpenter), the intention is also to draw out evidence of LGBT+ culture in what might be called more traditional literature (including Chaucer and Shakespeare). There is also a focus on connections with Cambridge, including the Uranian poets Charles Sayle (member of UL staff) and Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson (fellow of King’s College).

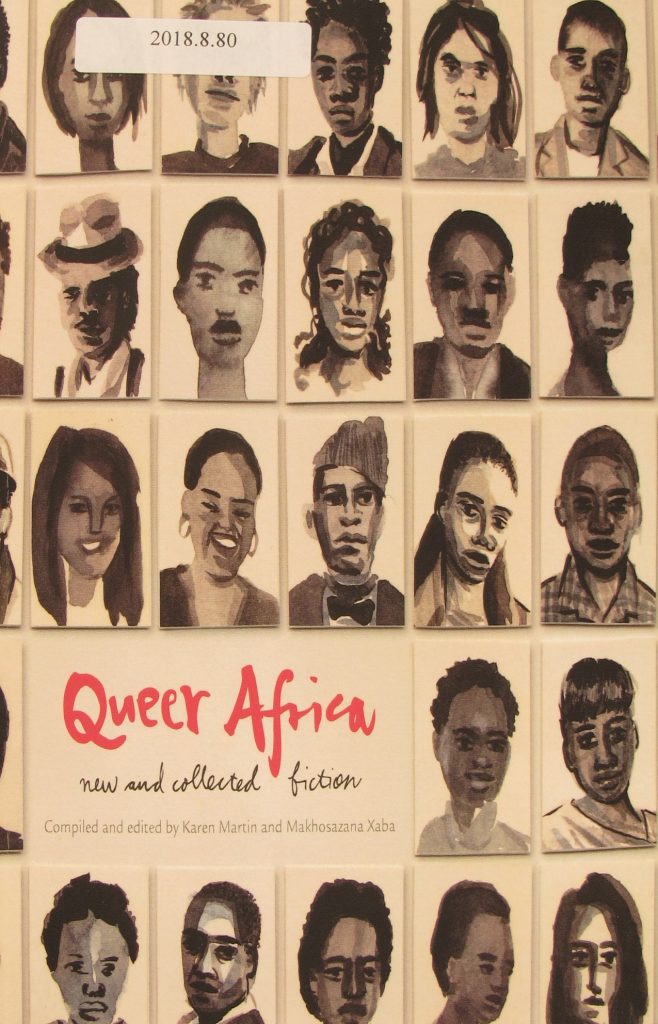

Although it is difficult to capture the breadth of material on display in the blog format, we hope that the imagery here gives a flavour of what was on show. The physical display intentionally juxtaposed old with new, without any attempt to impose a strict narrative from beginning to end, qualities captured here by focusing on imagery rather than text: some items are self-explanatory and others required more interpretation.

Poster by the Front d’Alliberament Gai de Catalunya (1979) from the collection of Hispanic ephemera recently presented to the Library by Dr Robert Howes

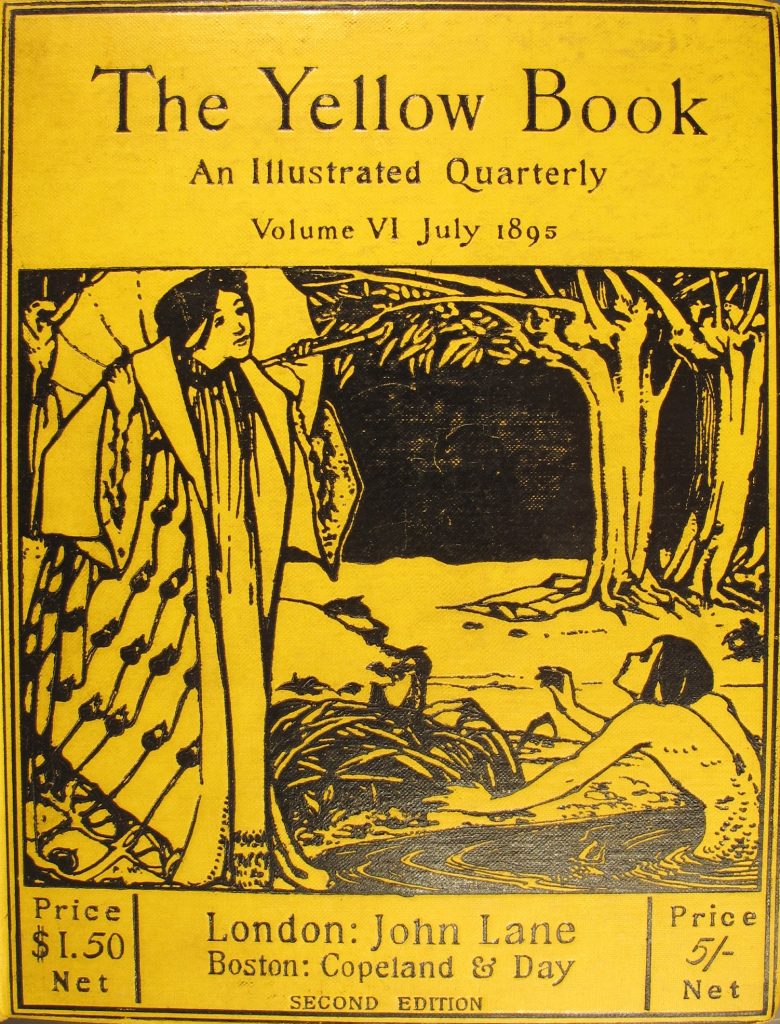

The Yellow Book (July 1895), associated with the Aesthetic and Decadence movements, included much work by flamboyant artist Aubrey Beardsley, who had illustrated Oscar Wilde’s Salome (T727.c.5.6)

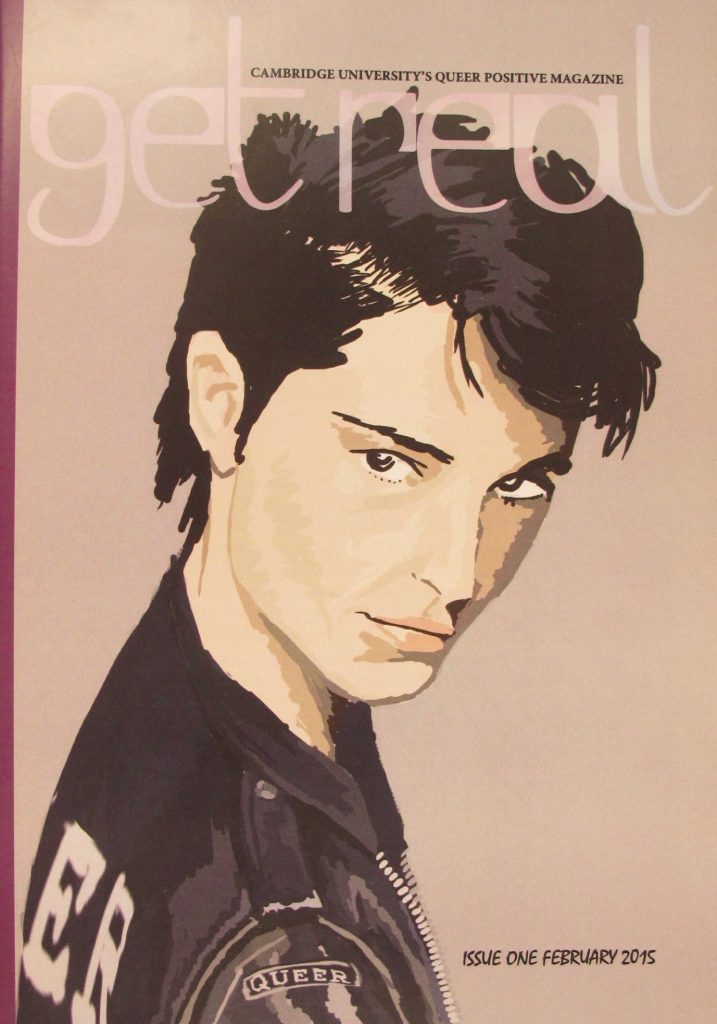

An issue of ‘Get Real’, Cambridge University’s Queer Positive Magazine, kindly lent by the CUSU LGBT group

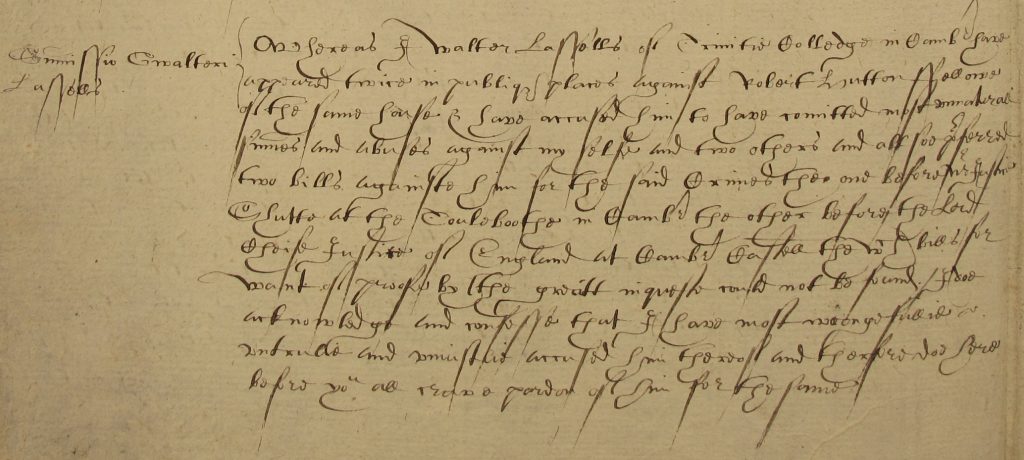

This record from the Vice-Chancellor’s Court, a place for arbitration in the University, detail a murky story involving students and a fellow at Trinity College in 1589. The fellow (Robert Hutton) is accused by a student (Walter Lassells) of ‘enticing’ him and two others to commit ‘unnatural sinnes and abuses’ (later referred to as ‘the abominable act of buggery’), as we see in the 3rd and 4th lines of text here. But all is not what it seems: Lassells later recants his accusation, noting that it was made ‘by the instigation of the devil’. It seems the student had hoped to avoid payment of debts to his tutor by defaming him. Such evidence speaks of the power such accusations had, and continued to have, in early modern England (VCCt.I.2, fol. 29v)

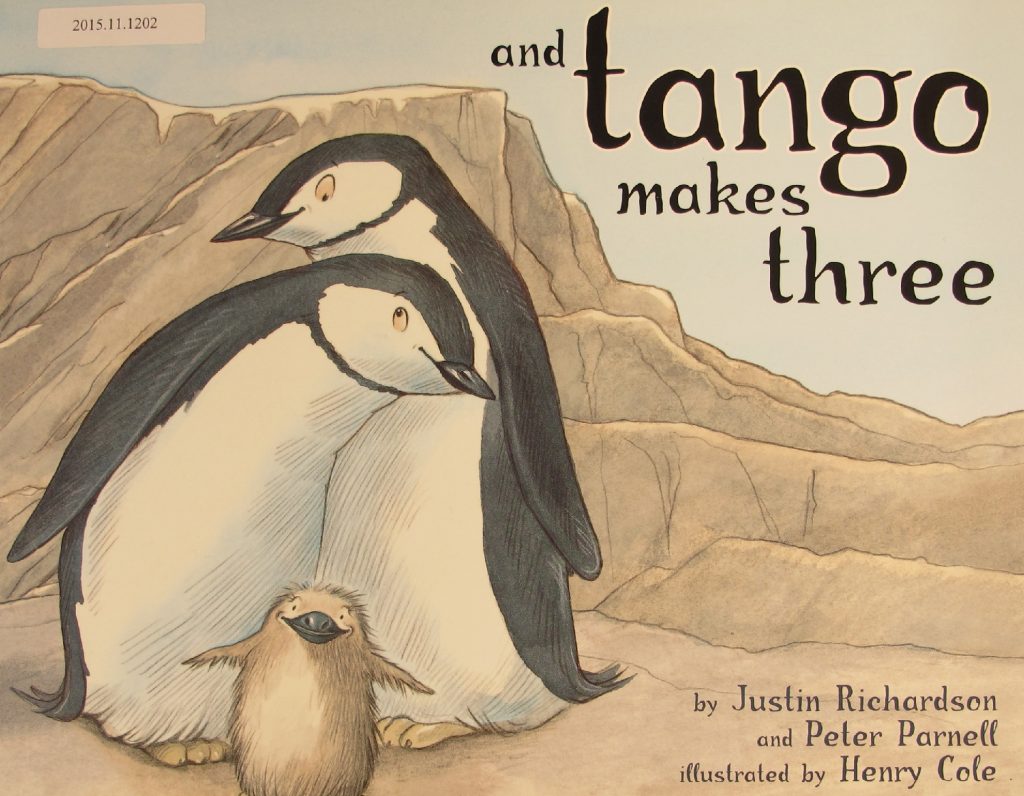

Probably the first book written for children about homosexuality in animals, ‘And Tango makes three’ (based on a true story and first published in 2005) tells the story of two male penguins, named Roy and Silo, who create a family together (2015.11.1202)

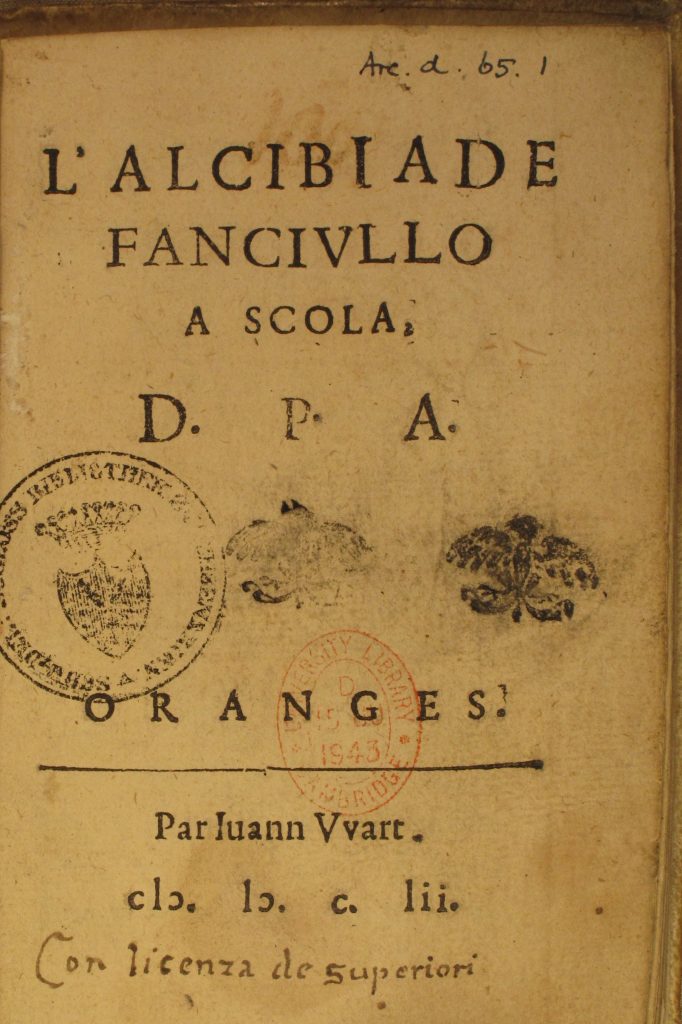

‘Alcibiades the Schoolboy’, loosely based on the form of Platonic dialogue, is an early defence of homosexuality; indeed, it has been called the first homosexual novel. (Arc.d.65.1)

Preparations for kabuki theatre (an elaborate dance-drama with a tradition of men playing female roles), printed in 1771. The central figure is being dressed in a female outfit (FJ.720.2)

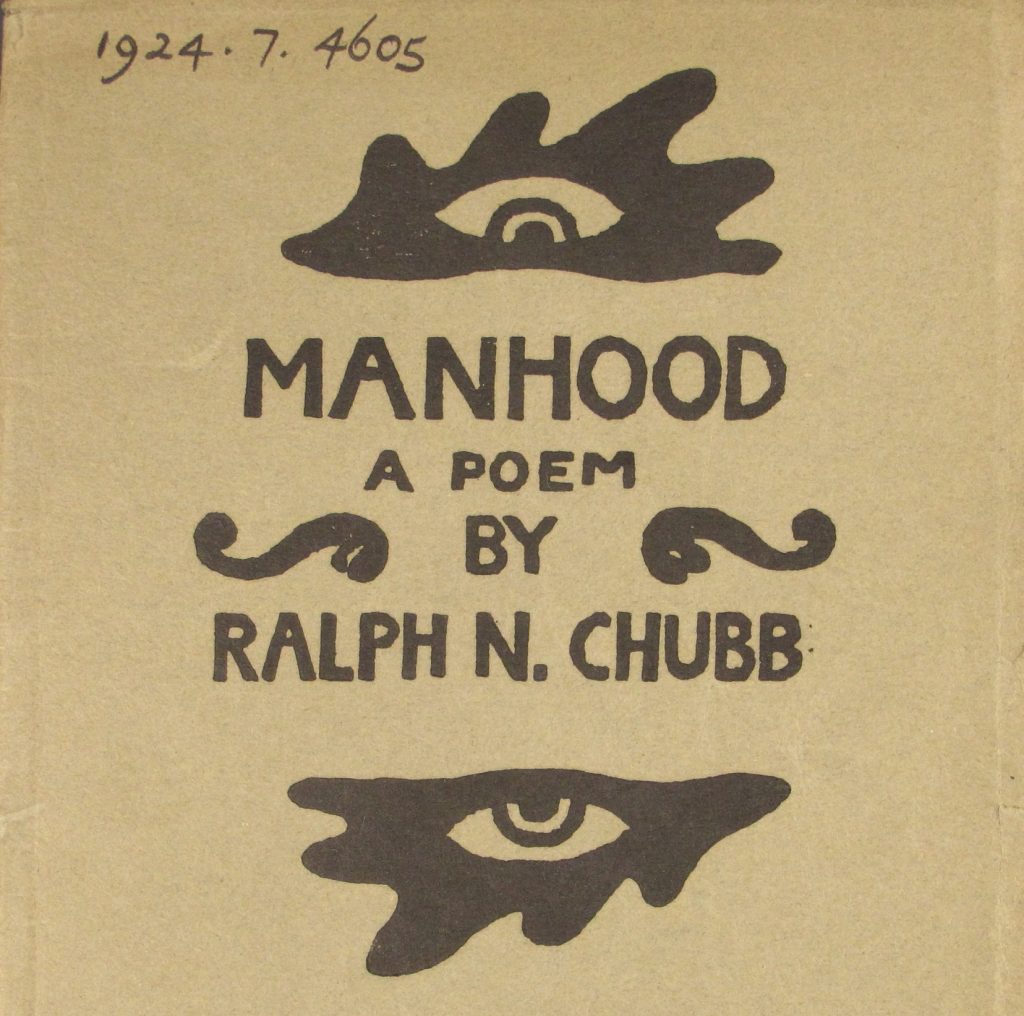

Educated at Selwyn College, Ralph Chubb’s work combined art and poetry. Like William Blake he produced a number of hand-coloured books in very limited editions. Manhood (1924)—a paean to the male form—is the first of his publications (1924.7.4605)

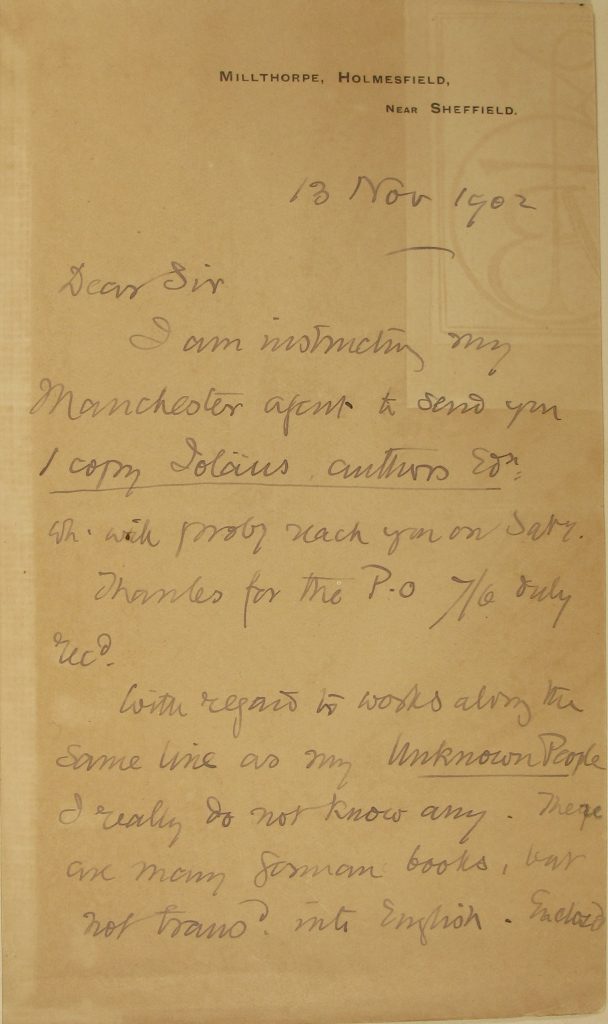

A letter dated 1902 from the poet and gay rights activist Edward Carpenter (a student at Trinity Hall) to A. T. Bartholomew, a member of UL staff, inside Carpenter’s Iolaus (an anthology of gay poetry and literature). Keynes.Y.4.40

This salacious Latin dialogue between two schoolboys, was written by P. G. Bainbrigge, a Trinity graduate, and published posthumously in 1926. It belonged to the Trinity College classicist and poet A. E. Housman, and came to the Library at his death in 1936 with about fifty other works of erotica (Arc.b.92.25)

The French essayist Montaigne and Estienne de la Boetie both served in the Bordeaux parlement and enjoyed a short but intense friendship until the latter’s early death in 1563. Montaigne edited his friend’s translation of Xenophon for publication, to which he appended this account of his death (Montaigne.1.7.20)

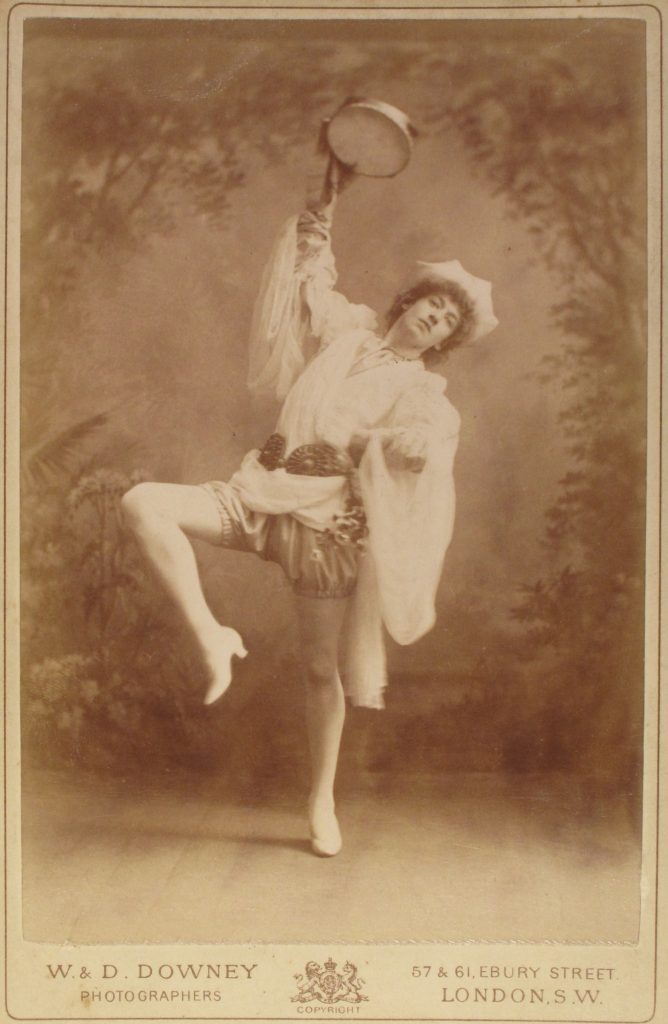

Photograph of the painter, playwright and dancer W. Graham Robertson, slipped inside a first edition of Oscar Wilde’s ‘Happy Prince and other stories’ inscribed by the author to Robertson. The two met around 1887, soon becoming lovers, and in 1892 Robertson was one of those given a green carnation to wear to the premiere of Lady Windermere’s Fan (Keynes.X.6.3)

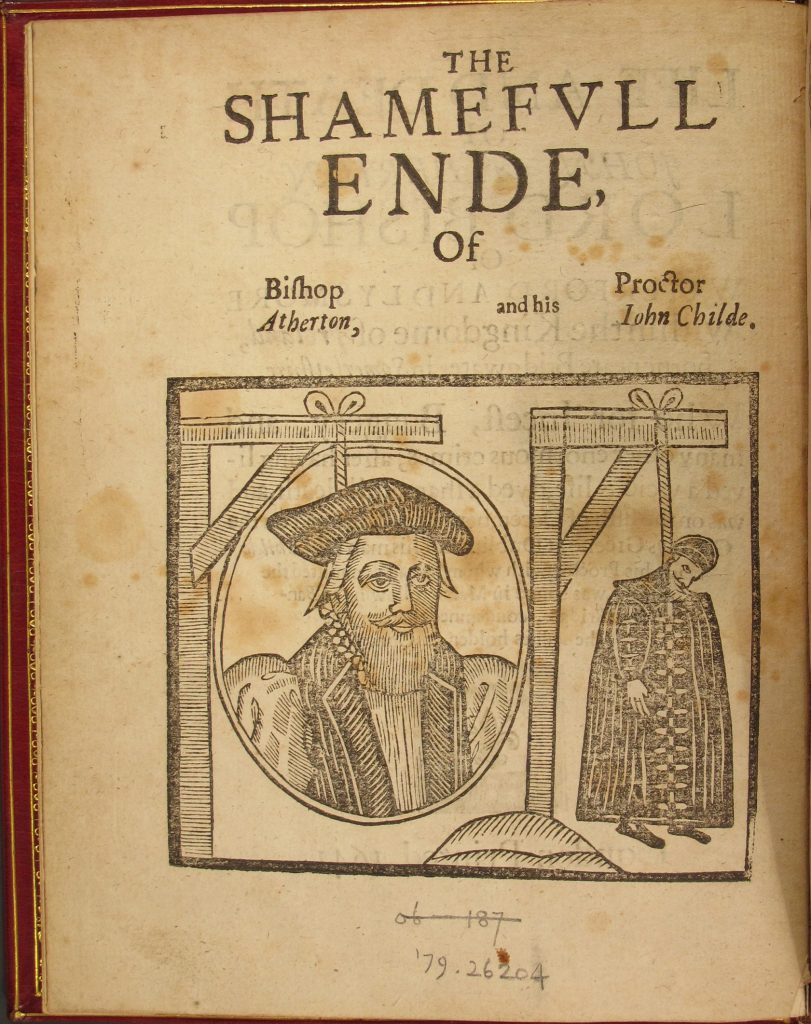

John Atherton studied at Oxford and joined the ranks of the Anglican clergy, becoming Bishop of Waterford and Lismore in the Church of Ireland. In 1640 he was accused of buggery with John Childe, his steward and tithe proctor. They were tried under a law that Atherton himself had helped to institute and both were condemned to death, their story recorded in this 1641 pamphlet (Hib.7.641.5)

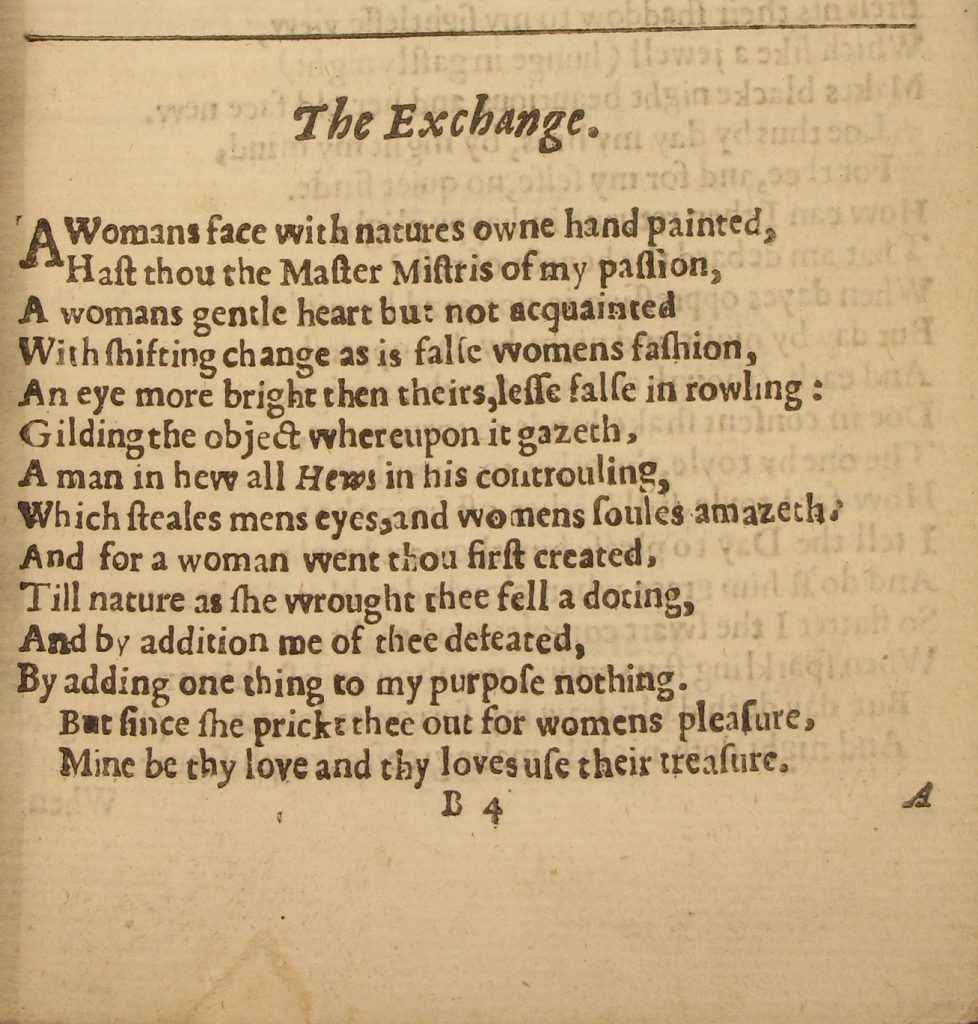

Shakespeare’s Sonnets, here in the 1640 edition of his Poems, have long been the subject of discussion, both when it comes to the identity of the dedicatee ‘Mr W. H.’ and the possibility that some of the verses may be addressed to a man. In sonnet 20 (here called ‘The Exchange’) the poet’s lover is ‘the Master Mistris of my passion,’ with the grace and features of a woman but devoid of the guile and pretence that apparently comes with female lovers (SSS.45.16)

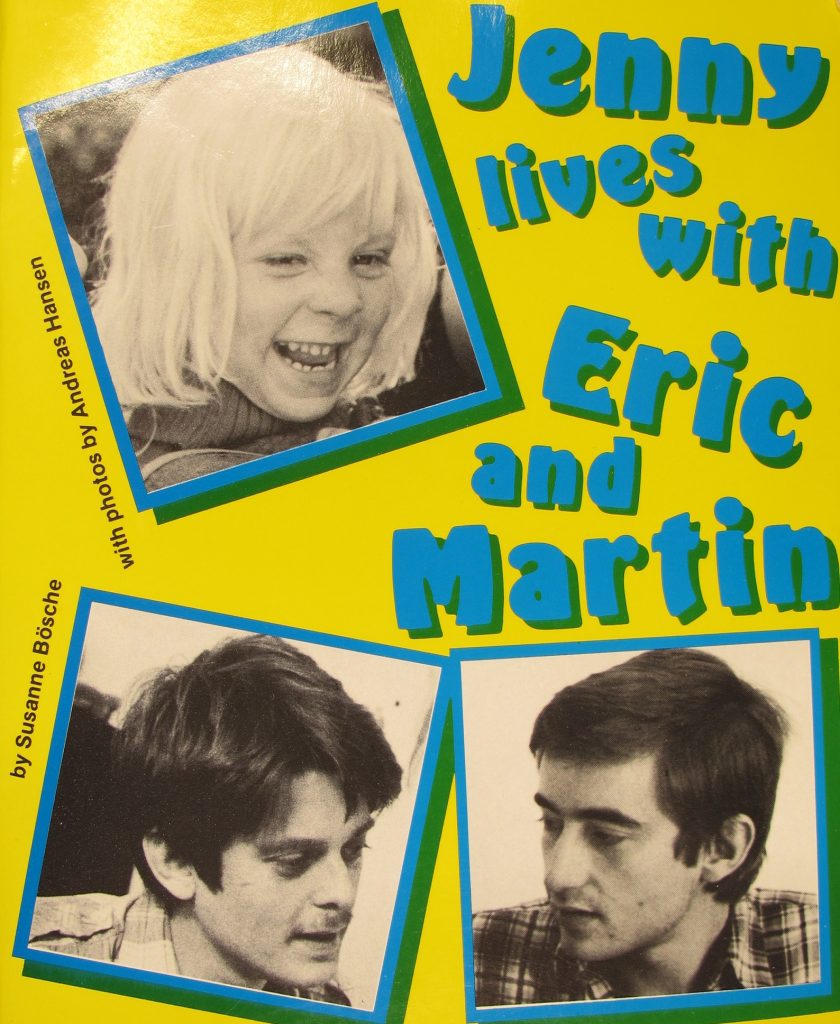

Originally published in Danish in 1981 this book was aimed at children with gay parents and aimed to normalise such family groups, in the hope that they might identify with five-year-old Jenny. The inclusion of the book in a London Education Authority teacher centre was enough to enrage the UK press, which fed into the ideology of Clause 28 (1984.9.1516)

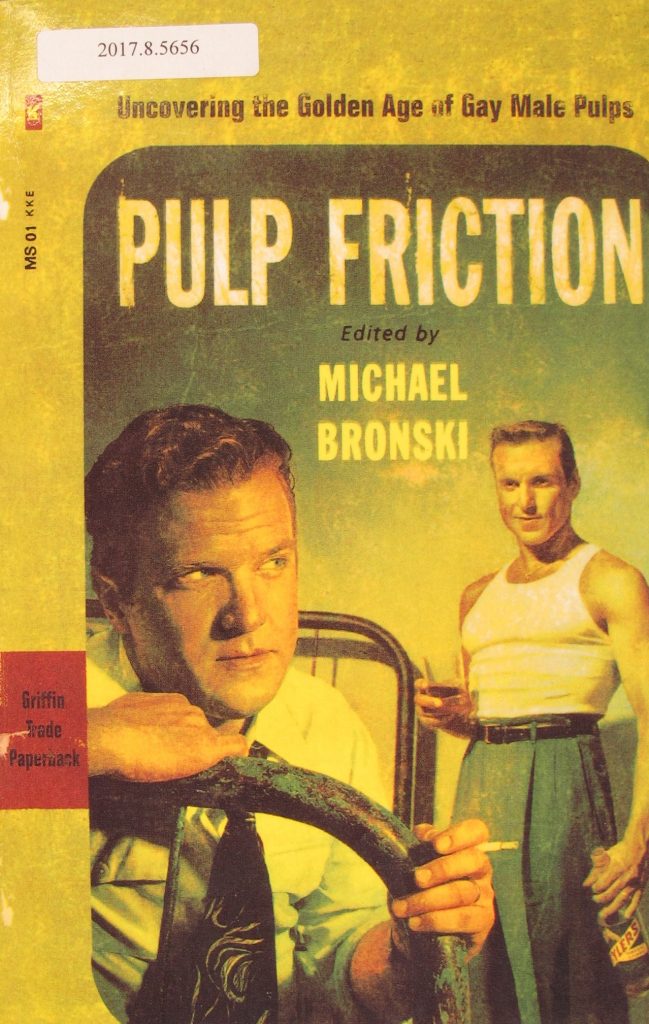

The recent work considers the growth and success of gay-themed pulp fiction in 1950s and ’60s America (2017.8.5656)

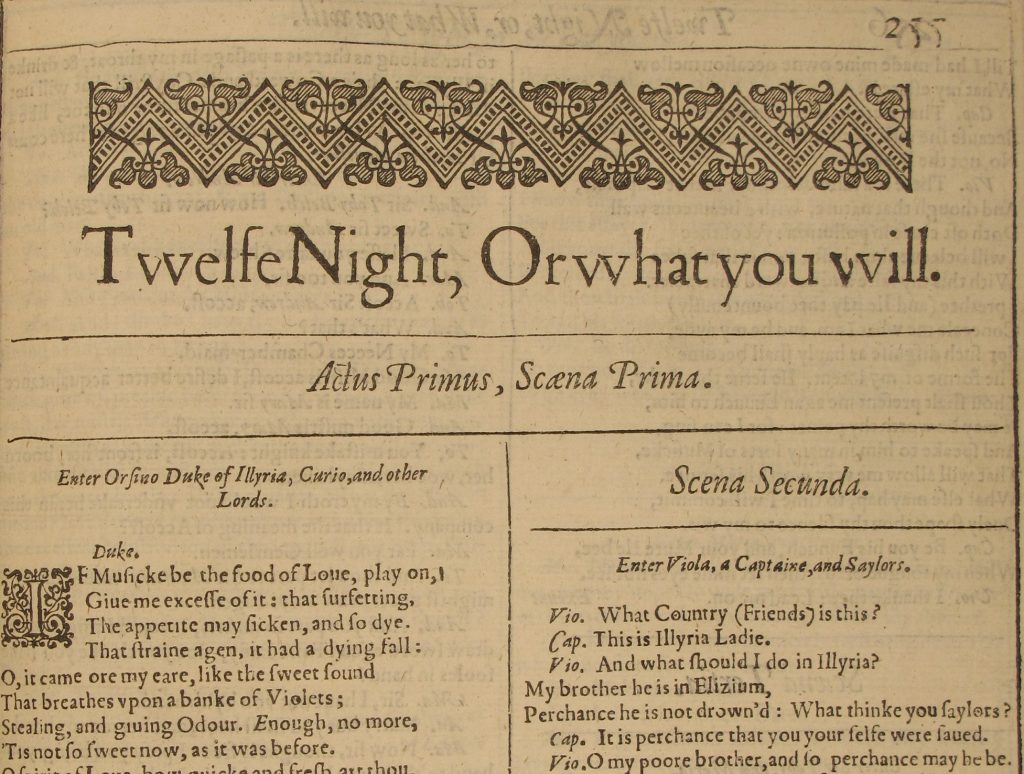

In Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night the lead female character dresses as a man. The change in gender is used as a joke, but there is more to think about: a woman can become a man, but only if it is not permanent and the effect of the change cannot be too great because she must change back to female once everything is settled. They are strong female characters, but must become men to protect themselves and ultimately solve the problem of the play. From the First Folio of Shakespeare’s works, printed in 1623 (SSS.10.6)

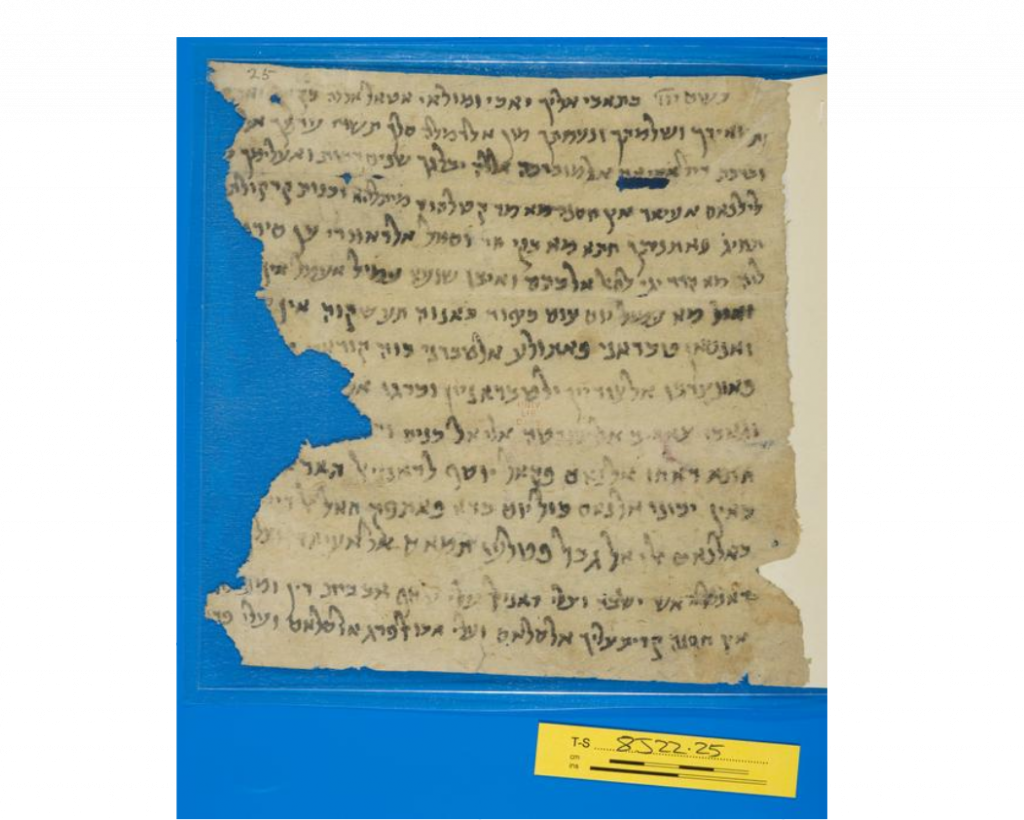

An eleventh-century letter from a Jew, Hasan son of Mu‘ammal of Ramla (near Jerusalem), to another Jew, Abu Nasr al-Ahwal in Fustat, Egypt. He describes how a disagreement arose among pilgrims on the holiest day of the Jewish year when, during a synagogue service, a man from Lebanon and a man from Tiberias appear to have become intimate. This greatly upset their fellow worshippers and the (Muslim) police had to be called to restore order for the continuation of the service (MS T-S 8J22.25)

(See the Genizah’s fragment of the month pages for more information)

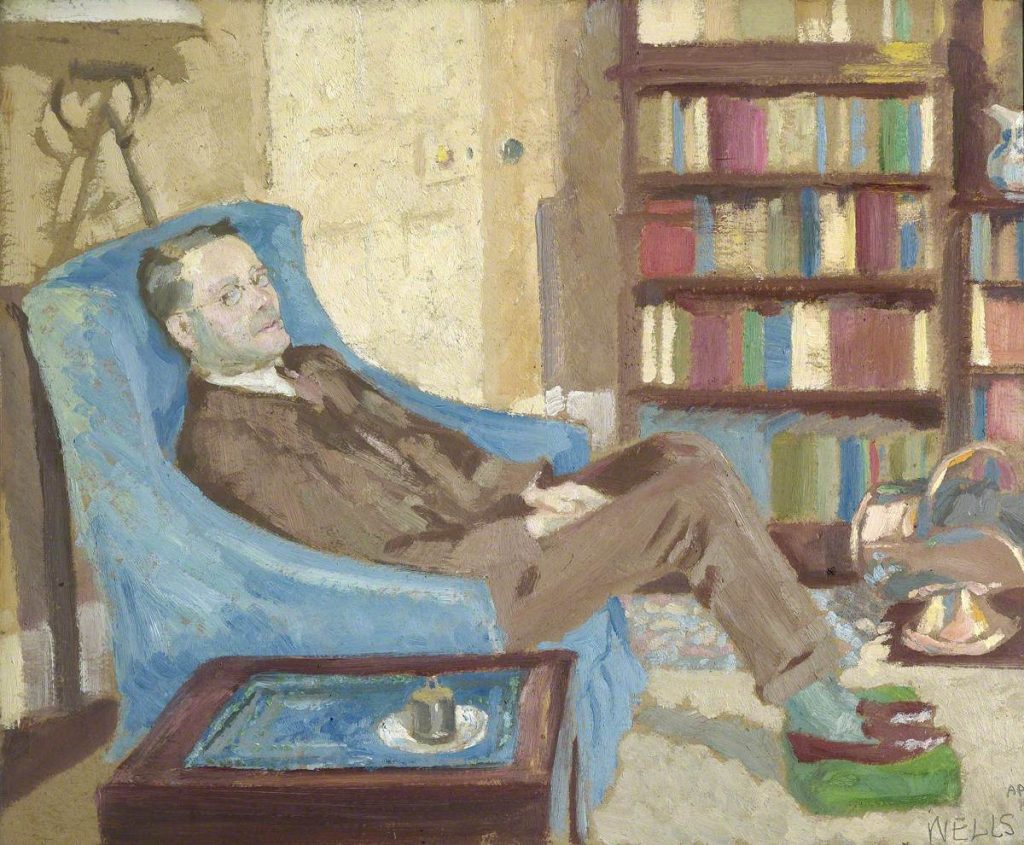

Portrait (1917) by John Wells of A. T. Bartholomew, member of UL staff 1900-1933, surrounded by books in his rooms at Pythagoras House (within the grounds of St John’s College). He arrived at the Library as a young man, ran it more or less single-handed during WWI and remained on the staff until his early death. Though not kept from his close friends, his homosexuality was largely kept a secret; it was said of him that he would tell potential friends ‘so that they might discontinue their friendship if they disapproved or found it embarassing’ (hangs in the Rare Books Department)

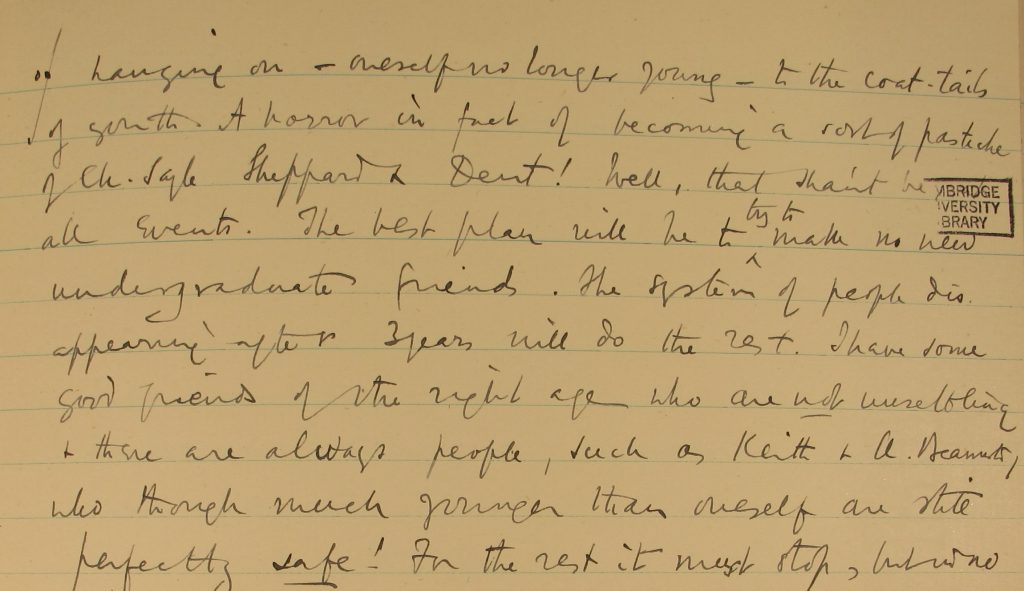

Theodore Bartholomew and Charles Sayle were both members of staff at the UL, then housed in the medieval Old Schools building. Both were homosexual and both, though they had numerous friends, lived somewhat closeted lives. Initially close, the two grew apart when Sayle (more than twenty years Bartholomew’s senior) complained his friend no longer visited him. Bartholomew, on the other hand, saw himself turning into Sayle, becoming old but ‘hanging on … to the coat-tails of youth,’ as we see from his diary. Their gloomy outlook on life, fixated on youth, can be seen in other gay men of the day (MS Add. 8786/1/13 – May 1921)