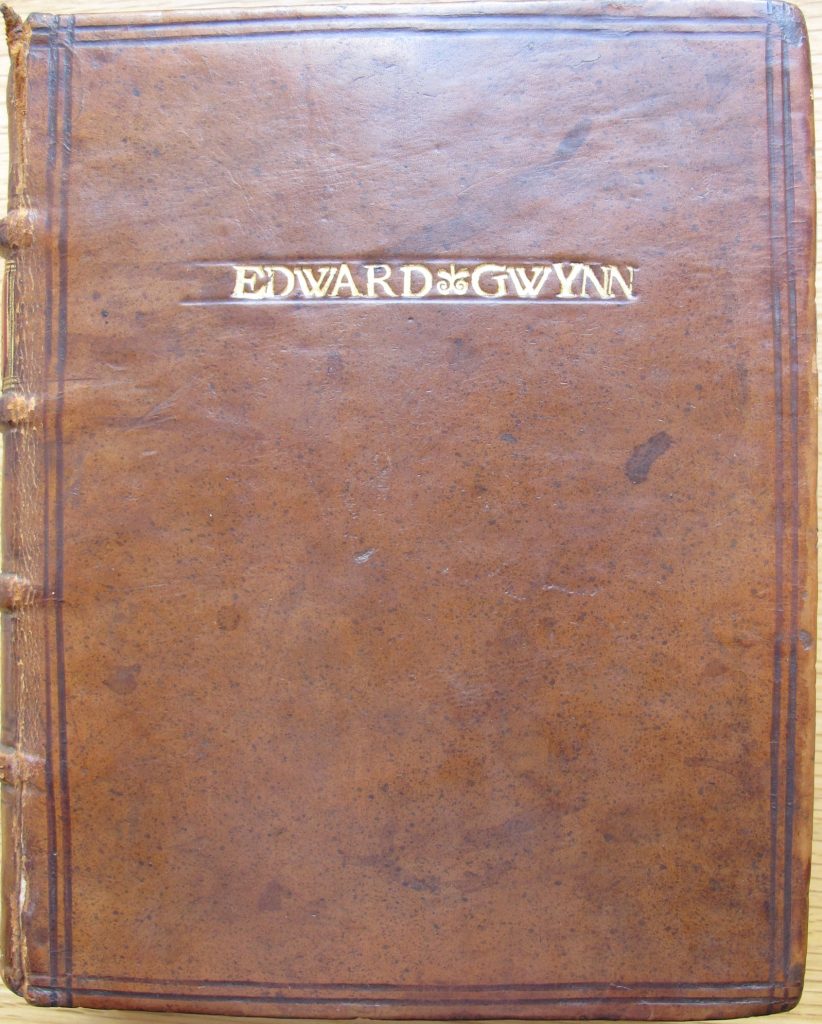

Edward Gwynn and his bindings

In 2009 a history of the British Library was published with the title ‘Libraries within the Library’, a phrase which might just as easily be applied to the University Library’s historic collections. Gift and bequest was the primary means by which the Library’s holdings were increased for much of the early modern period and our shelves tell the stories of a number of collectors whose libraries now reside – in whole or in part – within our collections. In the sixteenth century these included Thomas Lorkyn, Regius Professor of Physic, who left 300 medical books in 1591; in the seventeenth Richard Holdsworth stands out (his 10,000 books came to the Library in 1664 after a lengthy legal battle with his college, Emmanuel, who were also keen to secure the books); and in the eighteenth John Moore, Bishop of Ely, whose vast library of 30,000 books and manuscripts was bought by King George I and gifted to Cambridge in 1715. And it doesn’t stop there, for within Moore’s library are represented a number of earlier collectors whose books he acquired. Some are well known but one would be virtually unknown today were it not for the distinctive way he marked the bindings on his books: Edward Gwynn.

Very little is known about Gwynn himself, but he was probably born no later than c. 1590, entering Middle Temple in November 1610. From 1626 he lived with a friend, Alexander Chorley, in a building within the gardens of Furnivall’s Inn (another legal institution) just off Holborn in London. His will was made in 1645 (though not proved until 1649/50) and left ‘all my goods, chambers and bookes’ to his friend Chorley. How and when they were dispersed is still a matter of discussion but they presumably entered the second-hand book trade at some point following his death, and nearly 200 printed volumes have been traced in libraries across the world, including over 50 in Marsh’s Library (Dublin) and 26 at the Folger Shakespeare Library. Useful blog posts, with photographs of bindings, are to be found at St John’s Cambridge and St Andrews. Some of Gwynn’s books are incredibly important, including the so-called ‘Pavier Quartos’, a volume of nine 1619 Shakespeare quartos, the only set remaining in a seventeenth-century binding.

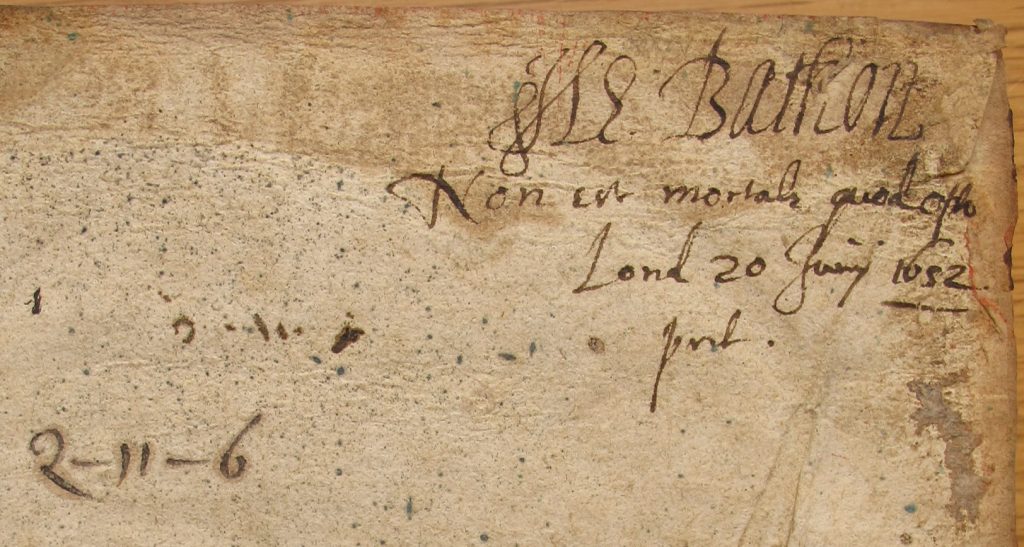

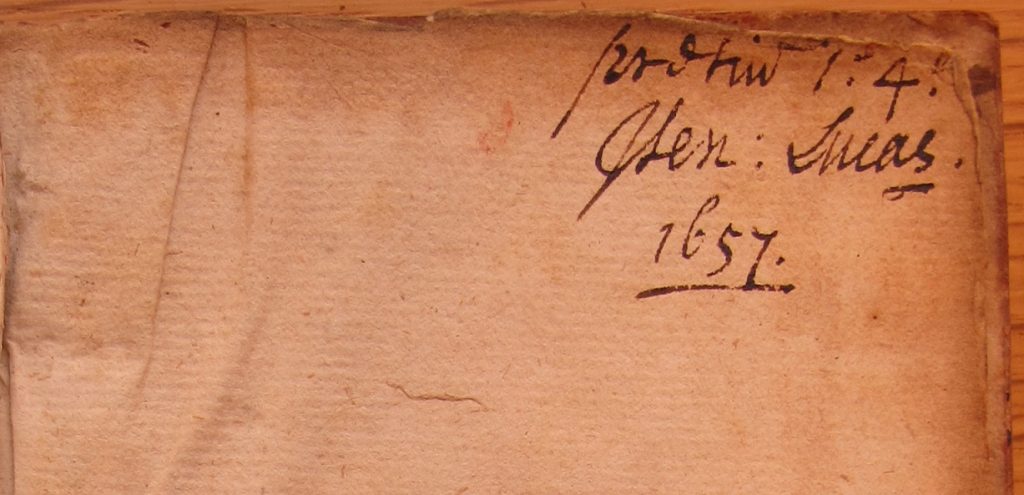

Cambridge has its share too, with books in several college libraries and the University Library. According to the current list on the Folger website, the University Library only has one Gwynn binding, but when one came across the desk for a reader in the Rare Books Room earlier this week I was spurred on to investigate further, and it seems that we have ten (six were identified in Charles Sayle’s provenance index, compiled in the early twentieth century). Interestingly seven of these came to us with the books of John Moore in 1715, so presumably he acquired them in London at some point between the 1680s (when he began to spend more time there) and his death in 1714. In his 1934 article William Jackson suggested, given that the known post-Gwynn owners were collecting in the 1670s and 1680s, that his books were probably dispersed about that time. Whilst this is true of Moore, two of our books show they were acquired much earlier, in the 1650s, perhaps pointing to an earlier dispersal (possibly directly by, or after the death of, Chorley). The earliest is Henry Bourchier, 5th Earl of Bath, who inscribed one of Gwynn’s books (a work on canon law by Konrad Rittershausen, printed in Paris in 1638) ‘He: Bathon’ followed by his Latin motto and the date 20 June 1652. Evidence of post-Gwynn acquisition is also to be found in a copy of the works of the Danish polymath Caspar Bartholin (concerning, amongst other things, unicorns and pygmies), printed at Copenhagen in 1628. In 1657 it was acquired, for 1s 4d, by Henry Lucas, founder of Cambridge’s Lucasian Professorship, MP for the University, and a great book collector, whose 4000 books came to us in 1664. Some of Gwynn’s books evidently did not travel far after his death; two of our volumes bear the ownership inscription of Fabian Philipps (1601-1690), a publisher of Royal books and also of the Middle Temple, who might have had them directly from Gwynn during his lifetime, or acquired them soon after his death.

The bindings themselves are not particularly special; generally inexpensive calf (occasionally reversed calf) and blind ruled (though occasionally gilt). Gwynn’s name appears in full to the upper covers, usually on one line if the book is big enough but sometimes over two lines, and his initials to the lower covers. Inbetween the two names on the upper cover is usually to be found a decorative tool (a flower, or a star-like tool, for example), except in those cases where the name is split over two lines when there is no tool. Interestingly there is a range of different tools used in this way. Some of Gwynn’s bindings bear a blind armorial stamp of three birds (Cornish choughs) within a shield, the whole enclosed in a rectangular triple blind fillet border (see the image at the head of this post). This crest is a Gwynn family crest and probably represents some earlier family collection (perhaps Gwynn’s father) rather than Edward himself. The Library contains at least one book with this crest but without Gwynn’s name or initials, so its connection to him is uncertain (Hildanus: Observationum & curationum cheirurgicarum centuria secunda. Geneva, 1611, shelfmark Keynes.A.2.1). Bringing the Library’s eight bindings together has also shown that four have coloured edges (the part of the textblock which can be seen when the book is closed), two with an alternating pattern of blue and red, and others with red and yellow. Such a feature on half of our examples would suggest that Gwynn himself commissioned the decoration, at a time when books faced foredge outwards on shelves, rather than spine outwards, as today.

Gwynn’s name has lived on through the survival of the books he owned and many more are likely to be hidden, unidentified, in library collections across the world. It seems highly likely that more remain to be found within the University Library’s own collections, particularly among the books of John Moore, whose voracious appetite for books in later seventeenth-century London saw him amass one of the finest libraries of the century.

Gwynn bindings in Cambridge University Library

Bartholin, Caspar. Opuscula quatuor singularia. Hafniae (Copenhagen): Excudebat Georgius Hantzschius, 1628. Shelfmark N*.14.15(G). Acquired by Henry Lucas in 1657 and came to the Library with his books in 1664.

Caius, Bernardinus. De alimentis quae cuique naturae conveniant liber. Venice: apud Evangelistam Deuchinum, 1608. Shelfmark Sel.3.146. Came to the Library in 1715 with the books of John Moore, Bishop of Ely.

Constitutiones patrie Foriiulii cum additio[n]bus noviter impresse. Venice: per Bernadinum de Vitalibus, 1524. Shelfmark S*.4.69(C). Title page inscribed (erased) ‘Fab: Philipps’, i.e. Fabian Philipps (1601-1690) of the Middle Temple. Came to the Library in 1715 with the books of John Moore, Bishop of Ely.

Fauchet, Claude. Recueil des antiquitez gauloises et françoises. Paris: Chez Iacques du Puys, 1579. Shelfmark S.4.22. Came to the Library in 1715 with the books of John Moore, Bishop of Ely.

The forme and maner of makyng and consecratyng of Archebishoppes Bishoppes, priestes and deacons. London: Richard Grafton, 1549. Shelfmark Rit.d.754.2. Came to the Library in 1715 with the books of John Moore, Bishop of Ely.

Gardiner, Edmund. Phisicall and approved medicines, as well in meere simples, as compound obseruations. London: Printed for Mathew Lownes, 1611. Shelfmark Syn.7.61.56. Came to the Library in 1715 with the books of John Moore, Bishop of Ely.

Rittershausen, Konrad. Differentiarum juris civilis et canonici seu pontifici libri septem. Paris: Lazari Zetzneri, 1638. Shelfmark Q*.11.6(D). Inscribed by the 5th Earl of Bath in 1652. Came to the Library before 1715.

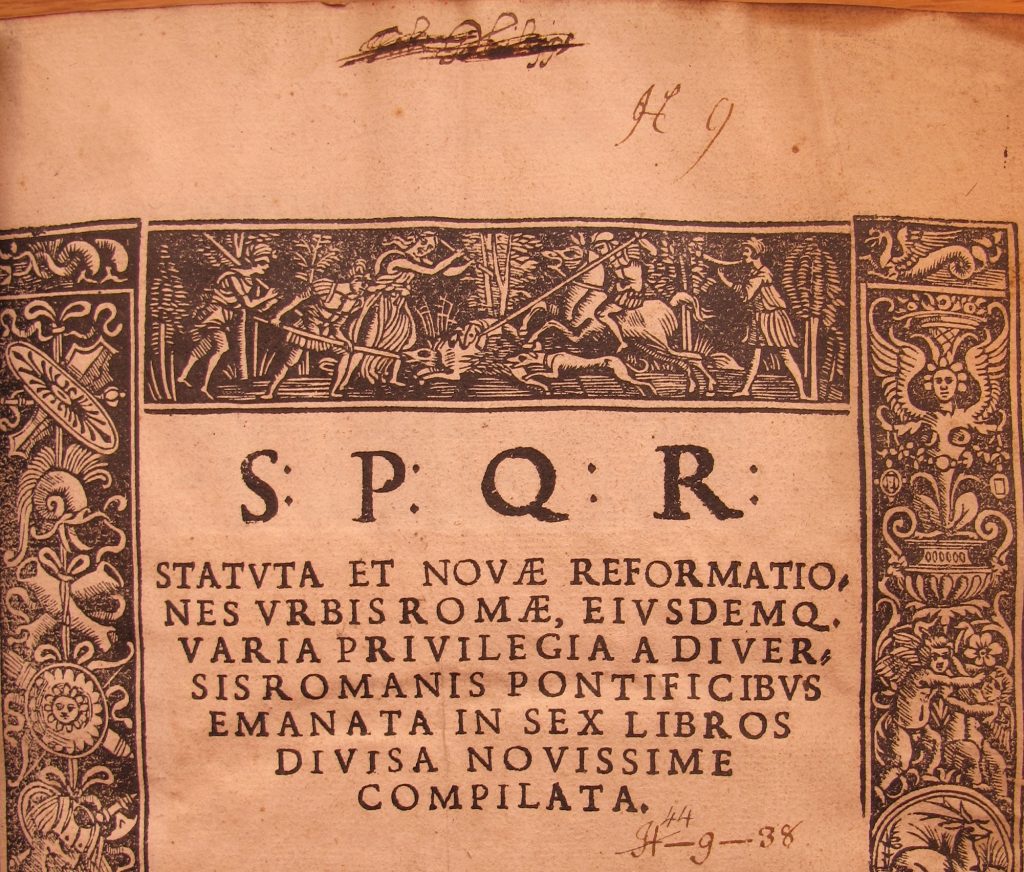

Statuta et novæ reformationes urbis Romæ. Rome: apud Valerium Doricum, ad instatiam Marci Antonii Guilliereti, 1558. Shelfmark H.9.38. Title page inscribed (erased) ‘Fab: Philipps’, i.e. Fabian Philipps (1601-1690) of the Middle Temple. Came to the Library in 1715 with the books of John Moore, Bishop of Ely.

Vivaldi, Giovanni Ludovico. Opus regale in quo continentur infrascripta opuscula. Paris: In vico Sancti Jacobi sub intersignio Divi Claudii, 1511. Shelfmark Td.54.25. Came to the Library in 1715 with the books of John Moore, Bishop of Ely.

And a sammelband containing six northern Italian imprints (Venice, Padua & Tarvisio) printed between 1600 and 1648, including an apparently unique poem on the nativity printed at Venice in 1618. Shelfmark Bb*.9.48(E). Came to the Library in 1715 with the books of John Moore, Bishop of Ely.