Mesmerised!

Now largely forgotten, the practice of mesmerism (a form of hypnosis named after the German doctor Franz Mesmer) was highly influential in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It centred around the belief that all living things have an invisible natural force, which can be physically harnessed, especially for healing purposes. Mesmerism was popularised in the early Victorian period by individuals including Chauncy Hare Townshend (1798–1868), an undergraduate at Cambridge who in 1840 published a book entitled Facts in mesmerism. A poet, clergyman, collector and friend of Charles Dickens, he bequeathed part of his collection of books, coins and fossils to the Wisbech and Fenland Museum 150 years ago, an anniversary being marked with a joint exhibition on mesmerism, held at the University Library but drawing on material from both institutions. Highlights include a letter from Charles Dickens to Townshend, and a crystal ball supposed to have been used by the pair (left). Townshend was introduced to Dickens (an enthusiastic supporter of mesmerism) in 1840. The two remained lifelong friends, Townshend dedicating to Dickens his volume of verse The three gates (1859), and Dickens dedicating Great expectations (1862) to Townshend (and later giving him the autograph manuscript, now in Wisbech). The letter, from Dickens, explains that he is far too busy to be mesmerised, ‘lest it should damage me at all’.

Mesmerism came about in the 1770s. Mesmer understood health as the free flow of the process of life through thousands of channels in our bodies, obstacles to this flow being the cause of illness. Overcoming such obstacles restored health, and when nature failed to do this spontaneously, Mesmer saw himself as aiding the efforts of nature. His theories were not always well received, however, and in 1777 he was forced to flee from Vienna after unsuccessfully treating a blind girl. Upon moving to Paris he could convince only one physician to join him, Charles d’Eslon, who encouraged him to write this short book on the subject. The practice was soon popularised in England by books like Ebenezer Sibly’s A key to physic, and the occult sciences (1795), a product of the experimental pursuit of scientific and psychological advancements in the late eighteenth century, providing a guide to what then was a relatively new theory in England which would soon attract a popular following among the public.

The key figure in the Victorian explosion of interest in mesmerism was John Elliotson, from 1831 Professor of Physic at London University (later UCL) and later Physician to University College Hospital. His early career in medicine was very successful, and his interests at the cutting edge (he was an early adopter of the stethoscope in England). But his passion for mesmerism led to friction with the College council and in 1838 he resigned his posts, going on to found the London Mesmeric Infirmary. It was Elliotson who introduced Townshend to Dickens, a friendship evident in Elliotson’s gift of his 1843 work Numerous cases of surgical operations without pain in the mesmeric state, another item loaned from Wisbech. Another connection to Elliotson is provided by a letter to him from the Harriet Martineau, also loaned from Wisbech, in which she discusses advances in mesmerism by the Scottish chemist William Gregory.

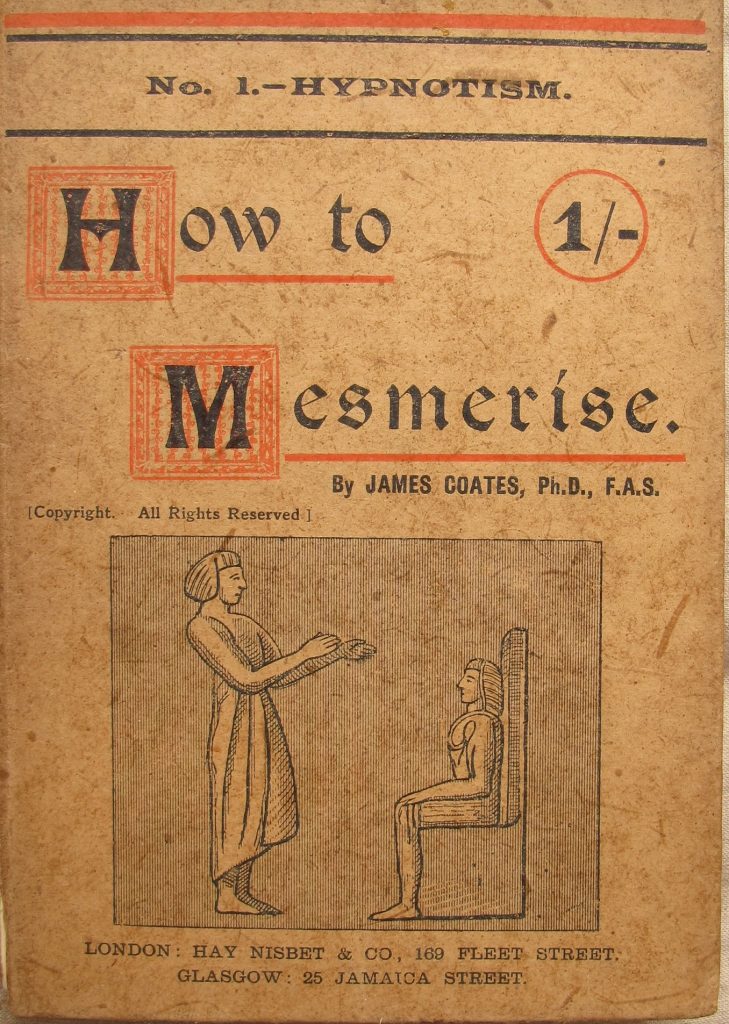

Mesmerism soon entered the public consciousness, influencing popular writers like Robert Browning, who wrote a poem on the subject, and Edgar Allan Poe. First published in December 1845 in two American journals, Poe’s short story, entitled Mesmerism “in articulo mortis” tells of a mesmerist who puts a man into an hypnotic state at the point of death. When later awoken, the man decomposes almost immediately into ‘a nearly liquid mass of loathsome, of detestable, putrescence’. Suggesting that attempts to appropriate power over death will never succeed, Poe’s story (initially released not as fiction but as a ‘true’ account) influenced the work of later writers including H. P. Lovecraft. The University Library’s holdings of secondary copyright material – until 28th October the subject of a major exhibition – contain many examples of popular Victorian publishing on the subject too. James Coates’s How to mesmerise begins with its application among Assyrian, Greek, Roman and Gallic cultures and notes amusingly that ‘The modern Frenchman, like his ancient forbear the Gaul, is particularly susceptible to mesmeric influences.’

This exhibition, in the Library’s Entrance Hall cases, is freely open to all during normal opening hours, until Wednesday 31st October. The Wisbech & Fenland Museum, where many pieces collected by Townshend are on display, is open between 10am and 4pm Tuesday-Saturday. Contact Liam Sims (ls457@cam.ac.uk) for further information.