Siegfried Sassoon on Armistice Day

The scenes of jubilation in Britain at the end of the First World War are familiar from often-reproduced images. Photographs taken in London and other cities show crowded streets, overloaded motor vehicles, and scores of excited faces. Not everyone was in a mood to celebrate on that day, however, and those with the closest experience of the fighting were often more subdued and reflective than many in the civilian population.

The poet Siegfried Sassoon was one such, and an account of how he spent Armistice Day can be found in his journal. The University Library’s pre-eminent holdings of Sassoon manuscripts include a full set of his surviving wartime journals, running from the time he arrived on the Western Front as a Second Lieutenant in November 1915, through his service at the Battles of the Somme (1916) and Arras (1917), to the last days of the War. The journals have been fully digitised in the Sassoon Journals collection of the Cambridge Digital Library, and here, reproduced by permission of the Trustees of G. T. Sassoon Deceased, is a transcript of his entry for 11 November 1918:

Monday 11th. I was walking in the water meadows by the river below Cuddesdon this morning – a quiet grey day. A jolly peal of bells was ringing from the village church, & the villagers were hanging little flags out of the windows of their thatched houses – the war is ended. It is impossible to realize. Oxford had much flag waving also – & signs of demonstration.

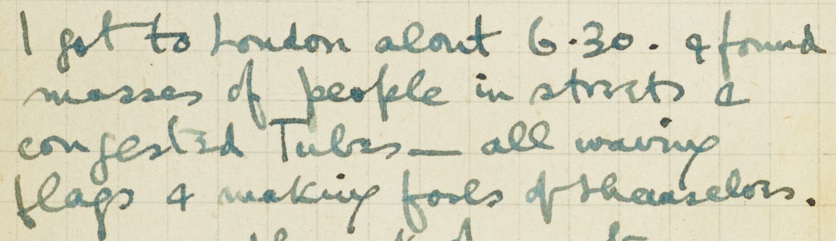

I got to London about 6.30. & found masses of people in streets & congested Tubes – all waving flags & making fools of themselves, – an outburst of mob patriotism. It was a wretched wet night, & very mild.

[Richmond] Temple took me to dine with some people called Bigham (in Cheyne Walk) – B. is a conventional civil servant – a Commissioner of Scotland Yard,* – small & meagre & prim. His wife is a would-be Colefax. Enid Bagnold was there, & a Mrs Helen Campbell – an American journalist, & a young Navarro, musical & effeminate. Also a man called Hugh Godley,† & a (Cosmo Gordon Lennox) man. They were all very excited & silly, & shallow. I hated them & their good dinner, & their sympathy with the mob flag waving. ‡Bigham & Godley argued that it is a very fine sight to see the people behaving in Bank Holiday style, & they got very angry with T. & self when we opposed their view.

It is a loathesome ending to the loathesome tragedy of the last 4 years.

† afterwards Lord Kilbracken

‡ ‘’ Lord Mersey

* This was wrong. (vide Who’s Who).

[The ‘footnotes’ are Sassoon’s own, and were added much later: Hugh Godley (1877–1950), a barrister, did not succeed his father as Lord Kilbracken until 1932. Charles Clive Bigham (1872–1956), far from being a ‘conventional civil servant’, had had a varied military and diplomatic career at home and abroad, including spells as an intelligence officer and as aide-de-camp to the Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland, and had served as Provost Marshal at the Dardanelles expedition; he succeeded to his father’s viscountcy in 1929. Sassoon was comparing his wife, Mary, to the society hostess Sibyl, Lady Colefax (1874–1950). Enid Bagnold (1889–1981) was already celebrated as the author of A Diary without Dates (1918), an account of her wartime work as a hospital nurse in London, and went on to be a novelist and playwright. Cosmo Charles Gordon-Lennox (1869–1921) was also a playwright. Richmond Temple, who had served in the Royal Flying Corps, knew Sassoon through their mutual friend, the journalist and gallery owner Robert Ross, who had died unexpectedly the previous month.]

I must be getting confused with another veteran of the war. In the report I had read, he (Siegried Sassoon) was travelling into town on the 11th and there was, as described, a drunk char woman (am I allowed to say that) on the train. It was early morning, and he was depressed, as I am sure were many who had endured the war.