Shanghai and the May 30th Movement: guest post by Elena Fulgheri

The Royal Commonwealth Society Department is very grateful to our colleague, Elena Fulgheri, for a guest post inspired by our most recent release on Cambridge Digital Library. Elena writes:

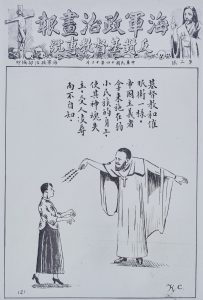

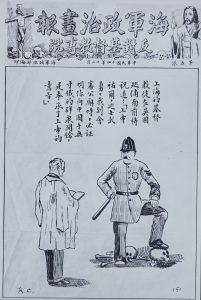

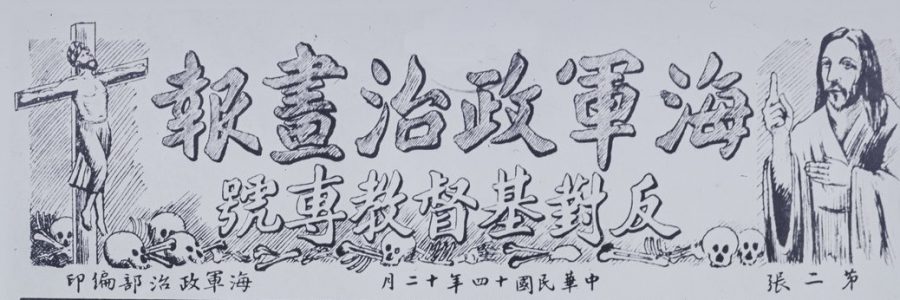

A collection of glass lantern slides, Y3011B(LS), includes three Chinese political cartoons, dated December 1925, which show a strong anti-Christian sentiment. They are precious testimonies of a turbulent period in the history of China and I have translated their captions in order to have a better understanding of their meaning.

The first, pictured at the left, declares: ‘Christianity, like hypnotism, is used by imperialists on weak peoples, making them lose their souls without knowing it.’

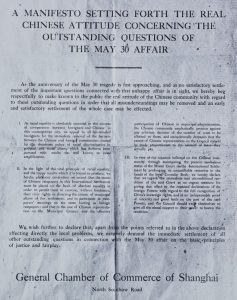

The three cartoons were published by the Navy Political Division (海軍政治部) in the illustrated magazine ‘The Navy Political Pictorial’ (海軍政治畫報). We have been unable as yet to discover any further information about the periodical or identify additional copies, making these examples very rare survivals. The subtitles show us that these were special anti-Christian issues, probably published on the occasion of the great anti-Christian demonstrations that took place in the Christmas weeks between 1925 and 1926. The cartoons come with a document that mentions the “May 30th Affair”. What happened on that day and how is it related to anti-Christian sentiment?

During the heyday of foreign imperialism in China during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, discontent was spreading among the local population over what were generally considered unfair privileges granted to foreigners. In that time foreigners – especially the Japanese and British – owned factories employing large numbers of Chinese workers under severe labour conditions, which often led to strike demonstrations. During one of these strikes in Shanghai, a Japanese employer shot into the crowd and killed a Chinese worker. The foreign police arrested the protestors for damage done to the machinery and for violence, but did not prosecute the Japanese owner who had opened fire. A memorial service was held for the shooting victim, but the police broke it up and arrested several students who were attending.

Consequently, on May 30 1925, thousands of protesters were out in the streets in Shanghai, inspired by leftist student groups, the Chinese Nationalist Party and the recently formed Chinese Communist Party, making speeches and distributing handbills. It was one of the biggest anti-imperialist protests the city had ever seen and it was hard for the Settlement police to control: when the masses approached the police station gates, a British officer gave the order to shoot. Depending on the source, about thirteen Chinese were killed that day and dozens more wounded. This started what is now known as the May 30th Movement (五卅运动), more than one year of protests of various levels of violence and intensity that took place in many cities around the country.

Translation of cartoon at left:

The Shanghai Christian offered the following prayer in front of the British policeman: ‘God bless you, brave policeman, once I get to court I will testify that your shooting Chinese unarmed masses was in obedience to God’s will.’

One of the outcomes of this conflict was an upsurge in anti-Christian sentiment, which in the 1920s was strongly returning to the limelight. The first two decades of the twentieth century had seen a massive growth of Christian activities in mainland China, especially in the medical and educational fields, and it was precisely against mission schools that the ideological attacks were concentrated. After the Shanghai Incident of May 30, the anti-Christian movement became markedly stronger, and a considerable number of students withdrew from mission schools, or were expelled for their participation in the protests. The anti-Christian sentiments of the population had found support in nationalist and anti-imperialist propaganda, and had in turn fuelled it. Property of Christians was plundered and destroyed, churches and schools were occupied, and by the end of 1927, over 3,000 missionaries had left China. Mission schools and hospitals were closed or left to Chinese staffs, and churches experienced a massive dislocation of their work.

The RCS has digitised two photograph collections illustrating the educational, social and medical work of missionaries in China, that of the Church Missionary Society and the medical doctor Lewis Paton. We are very grateful to Cliff Webb for supporting the imaging of these fascinating political cartoons as part of our glass slide digitisation project. We look forward to the completion of the project later this month with the release of the final 1,000 images.