Notebooks from the Steppe: William Bateson’s research trip to Central Asia, 1886-1887

To mark the digitisation of the William Bateson Archive and Bateson-Punnett Genetics Notebooks on Cambridge Digital Library, we are delighted to present a guest post by journalist and author Nick Fielding.

The name of William Bateson (1861-1926), the first professor of biology at Cambridge and later director of the John Innes Institute, is not well-known today. His unorthodox approach to his subject – and his argumentative personality – may have something to do with that. But in fact, Bateson was a pioneering figure in what became the science of genetics – a word, incidentally, that he coined. He translated the work of Gregor Mendel on plant hybridisation into English and disputed aspects of the Darwinian theory of evolution.

Today, after almost a century of obscurity, his writings are drawing a new audience who perhaps recognise that Bateson had a point or two. Alan G Cock and Donald R Forsdyke note in their biography of Bateson[1], that not only did he bring Mendel’s work to the attention of the English-speaking world, but he also dominated the biological sciences in the decades after Darwin’s death in 1882. In more recent times, the newly-formed discipline of Evolutionary Bioinformatics owes its existence to his work. His contribution to the early development of genetics is still playing out today.Cambridge University Library is now in the process of digitising its substantial collection of Bateson Papers and it is these that have attracted my attention – although my interest is not strictly scientific. Indeed, I am ill-qualified to judge whether Bateson was on the right track in his critique of Darwin or in his understanding of chromosomes. But some of Bateson’s early papers are of great interest to me as a traveller and writer on Central Asia.

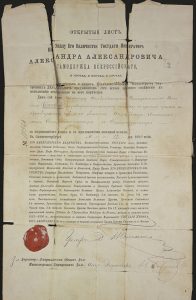

Why Central Asia? Because in 1886-87 Bateson spent months alone in the northern steppes of what is now Kazakhstan collecting tiny snail fossils. He set out to examine the fauna of the lakes and dried-out lake basins in this remote part of the world with two objectives: first, to find creatures that still survived from the days of a vast Asiatic Mediterranean sea that once covered this region; and second, to study the salt lakes in the steppe to learn how far the infinite variation of conditions affected and changed the forms of their fauna.

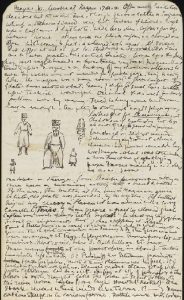

Again, I repeat, I have no interest in his scientific work. It is his other output that interests me. During his long and lonely sojourn on the steppes Bateson kept in regular contact with his family, sending letters back to England which are full of detail of the people he met – the Kazakh nomads, the Tatars, Kalmucks and, of course, the Russians. Some of those were published by his wife in 1928[2]. He also kept a detailed set of diaries in which he recorded day-to-day events, often making little pen portraits and sketches of the people and things he saw. These form part of the University’s collection, all of which is now in the process of being digitized and put online.

Having had a chance to study the files containing the diaries and other early material, it is perhaps worth providing a few quotes that will give you an idea of the man. Let’s start with his mention of a visit to the British Embassy in St Petersburg in April 1886:“Dined at Embassy. Sir R Morier (the ambassador, Sir Robert Morier 1826-93-ed) rather a loud person, but decidedly clever and well informed on his own subject, but knows no Russian (not even written characters). Somewhat civic in style. Lady Morier a sultry, ignorant, contemptuous person, evidently regarded the entertainment of scientific strangers as an evil hardly to be borne, which view she was at no pains to conceal. Neither of these persons were aware that the Hermitage contained any Spanish pictures, which was remarkable. NB Sir R. until recently was Spanish ambassador.”[3]

Clearly Bateson did not suffer fools gladly. Nor was he a shrinking violet himself. One diary mentions his armed pursuit for many miles of a group of camel thieves. He also describes another tricky moment close to the Aral Sea. Having found a waterhole for his horses, he was shocked when a caravan of 40 camels arrived, threatening to drink all the water and turn it into a muddy trough:

“The camels were herding around. Much objection and now, when I drew my revolver and roared out that I shd. shoot the first camel that drank there, that there was water higher up, good enough for the camels, it was true. No camels did drink and were hastily removed.”[4]

A few days later, at the end of August, he describes the custom of bride-chasing that still exists in parts of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan:

“Then a girl came out on a horse. She was dressed in crimson plush which is much affected by these ladies. She rode a mile or two and two or three of us tried to catch her, which is done by stroking the back and that of the horse with a whip. I failed to catch her. She had an excellent horse which had the action of a thoroughbred (a Turcoman?).”[5]

Bateson also offers one of the earliest descriptions of Kokpar, an ancient sport that involves large groups of men on horseback fighting over the carcase of a dead headless goat. The game is still played today in many countries across Central Asia.“The goat is beheaded and laid on ground and all try to pick it up from the saddle. When a man gets it up he is allowed to start full speed and all try to grab the goat. This goes on for an irregular time and at last someone who has ridden a long way with it makes for someone’s tent and throws the goat at the door. The woman of the tent is then expected to give him a present.”

Bateson adds that he was then asked to pay for a goat for a session of the game: “I then bought a goat and threw it to be raced for. The wretches brought it back to me – now I had again to fork out!”[6]

The notebooks contain countless more stories and the Bateson files also include dozens of remarkable photographs, some of them developed at what must have been one of the earliest photography studios in Siberia, based in Orenburg. His fine photographic portraits of the Kazakh nomads in particular are unusual for their rarity.

All this material is now available online on Cambridge Digital Library’s website. In itself it has little bearing on his scientific work, but in another context it represents a wonderful and unique archive of words and images from the steppe – at that time a land as distant and unknown as the densest jungles of Africa and South America.

[1] Alan G Cock and Donald R Forsdyke, Treasure Your Exceptions: The Science and Life of William Bateson, Springer, New York, 2008.

[2] William Bateson, Letters from the Steppe written in the years 1886-87, Methuen & Co, London, 1928.