Discoveries in the reading rooms

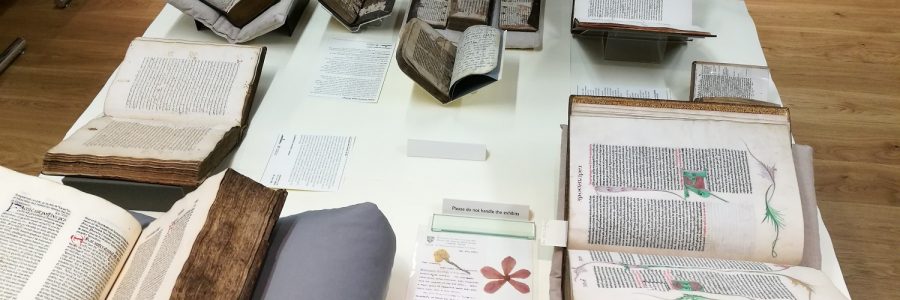

Readers working with material in the University Library’s Special Collections reading rooms are accustomed to discovering new and exciting things every day, whether that be a previously un-noticed annotation or a connection between texts and thoughts made only after close reading. Sometimes it might be finding pages of a book which are still attached to each other where the printed sheet is folded, the bookbinder having failed to trim the edges of those pages; the reader for whom they are opened is the first to see what is printed on those pages, after many years on the Library’s shelves. Sometimes readers and staff discover objects left behind by owners of books who studied them before they were acquired by the Library. Communicating the excitement of these discoveries to members of the public is an important part of the Library’s work, and a new exhibition in the Entrance Hall display cases (until the end of April) intends to bring some of this to visitors.

It is an offshoot of a very successful event held for the University Science Festival in March, which attracted 130 people to the Milstein Room. I wasn’t expecting that! was a pop-up display to complement the current exhibition Discovery, marking the 200th anniversary of the founding of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. The material on show included works by world-changing scientists associated with the University including Stephen Hawking and Jocelyn Bell Burnell, alongside discoveries made more recently by the world-changers of the future. Several of these had been spotted in the Rare Books Reading Room only in the last few months, including a book whose illustrated woodcut had been pricked with a pin, leaving holes which showed when visitors switched on a light below the page. This was a preparation for pouncing, an early form of reproduction where a dark powder was tapped over holes made in a page so that a dot-to-dot copy was made on the sheet below. A postgraduate student working on the text spotted this and thought we ought to know, as it hadn’t been noticed by a previous scholar looking at the work. An earlier post on this blog describes the process in more detail.

While much of the display was for viewing only, there were also items to enable visitors to make their own discoveries. Their skills of observation were tested with a map in whose contour lines an elephant had been hidden; staff were available to point this out, though many did spot it without help. A table was set aside with material that was intended for handling, such as pop-up and musical books; our status as legal deposit library means we receive such unexpected marvels as Honk if you like honkers; with a honker that really works! (though in fact it was a slightly disappointing squeak), and examples of the paper architecture of Robert Sabuda whose 12 days of Christmas finishes with a pop-up tree with twinkling lights.  One of our younger visitors made a new discovery on the night; the book-which-is-also-a-fire-engine which we had set up for climbing into has a pop-up windscreen which had escaped our notice.

One of our younger visitors made a new discovery on the night; the book-which-is-also-a-fire-engine which we had set up for climbing into has a pop-up windscreen which had escaped our notice.

The event is followed by an edited version of the display in the Entrance Hall of the University Library. The exhibition includes some additional discoveries made as recently as the last two weeks. One of these is pleasingly seasonal; an early sixteenth-century Processional (Norton.c.100) was fetched for a reader and on return, I had a look through the pages, having a personal interest in early music. Nestled into the gutter of the page opening the liturgy for Palm Sunday were fragments of palm leaf, age unknown, which must have been left there after the book was used in a service before it came to the University Library. There are also wax droplets on several pages, notably at the prayers for the sick and the departed. Encountering this evidence of use gives a unique connection to those who read these books; it may not be a world-changing discovery on a par with pulsars, but these unexpected signs of our shared human experience give a new perspective on the past.