Conflicting Chronologies: A New Exhibition at the Whipple Library

A guest post by Meira Gold, PhD student in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science. Her research concerns the history of Victorian Egyptology and the origins of archaeological fieldwork.

The latest rare book exhibition at the Whipple Library in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science is now open. Showcasing rare books from the special collections at both the Whipple and Cambridge University Library, Conflicting Chronologies explores some of the nineteenth century texts that debated the age, origin and development of early Egyptian civilisation.

Conflicting Chronologies is on display at the Whipple Library 1st May to 27th September 2019, Monday-Friday, 9.15am-5.30pm. The exhibition is free to attend and open to all – do come and visit!

“On the lookout from the pyramids of Egypt,” The Illustrated London News, vol. 81, no. 2260, 26 August 1882, p. 213 (CUL NPR.c.313)

The deep human past was a key arena for Victorian intellectual controversy. Were humans older than the biblical tradition of 6,000 years? Where had we come from? How were we related? The term “prehistory” first appeared in English in 1851. Ancient Egypt soon emerged as a critical juncture between prehistoric and historic time and became a symbolic place of debate. Amidst British control of semi-colonial Egypt, British geologists, philologists, ethnologists, anthropologists, archaeologists and astronomers identified traces of the remote human past in the region. Many attempted to answer the question: who lived in Egypt before the pharaohs? The exhibition displays publications by influential writers such as Charles Lyell, Leonard Horner, John Lubbock, and Edward William Lane, amongst others. Below I’ve highlighted some of my favourite pieces…

Joseph Hekekyan Bey, A Treatise on the chronology of Siriadic monuments (London: Taylor and Francis, 1863) (CUL Mm.32.53)

One of the more obscure books on display is A Treatise on the Chronology of Siriadic Monuments by Joseph Hekekyan (1807-1875), an Armenian engineer in the Ottoman-Egyptian government’s service. Hekekyan collaborated with Scottish geologist Leonard Horner (1785-1864) in the 1850s to supervise geo-archaeological excavations at the ancient sites of Memphis and Heliopolis. They analyzed the Nile flood sediments that had accumulated around pharaonic antiquities to show that “civilized” humans had lived in Egypt for at least 13,371 years. (To learn more about Horner and Hekekyan’s research, see Meira Gold, “Ancient Egypt and the Geological Antiquity of Man, 1847–1863”, History of Science, 2018)

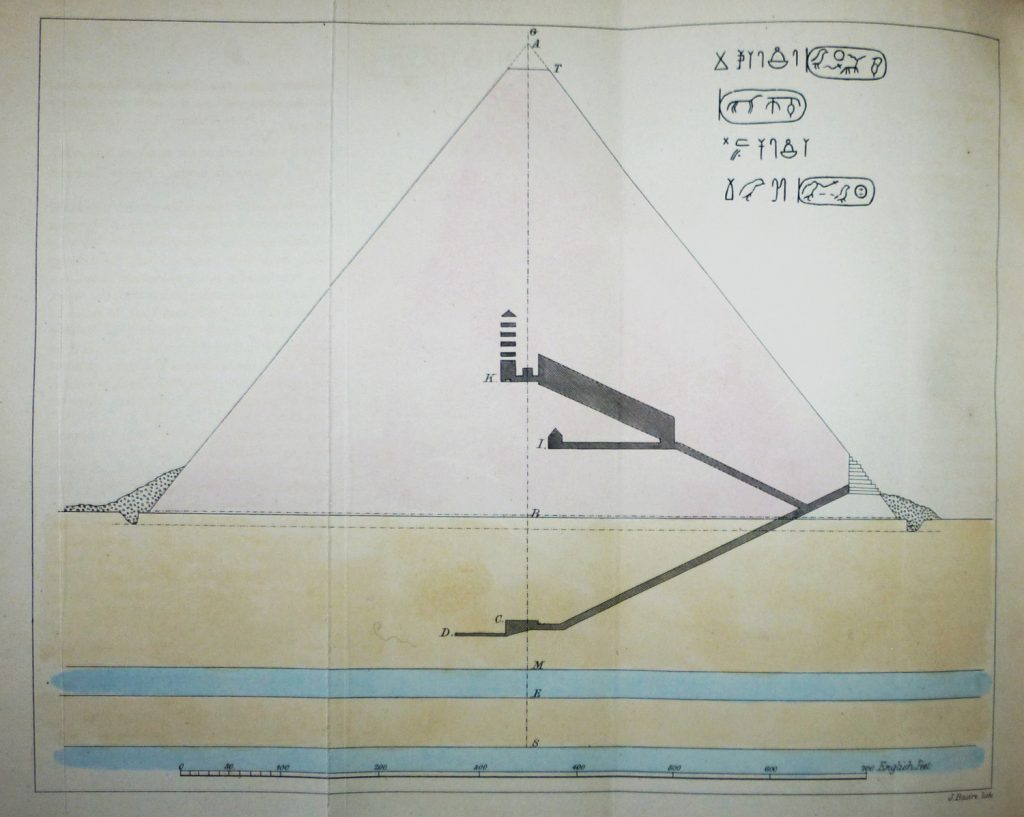

Hekekyan later published his own monograph on the topic of “astrogeology” —the first time that word was printed. He argued that ancient Egyptians used “astrogeological science” to build their oldest monuments, including the great pyramid at Giza. He termed these monuments “Siriadic” because their measurements corresponded to the revolutions of the star Sirius. According to Hekekyan, Siriadic monuments were evidence of the ingenuity of “the remotest generations of mankind.” Hekekyan’s book was not widely circulated. The pages of this particular copy are actually uncut, meaning it has never been read!

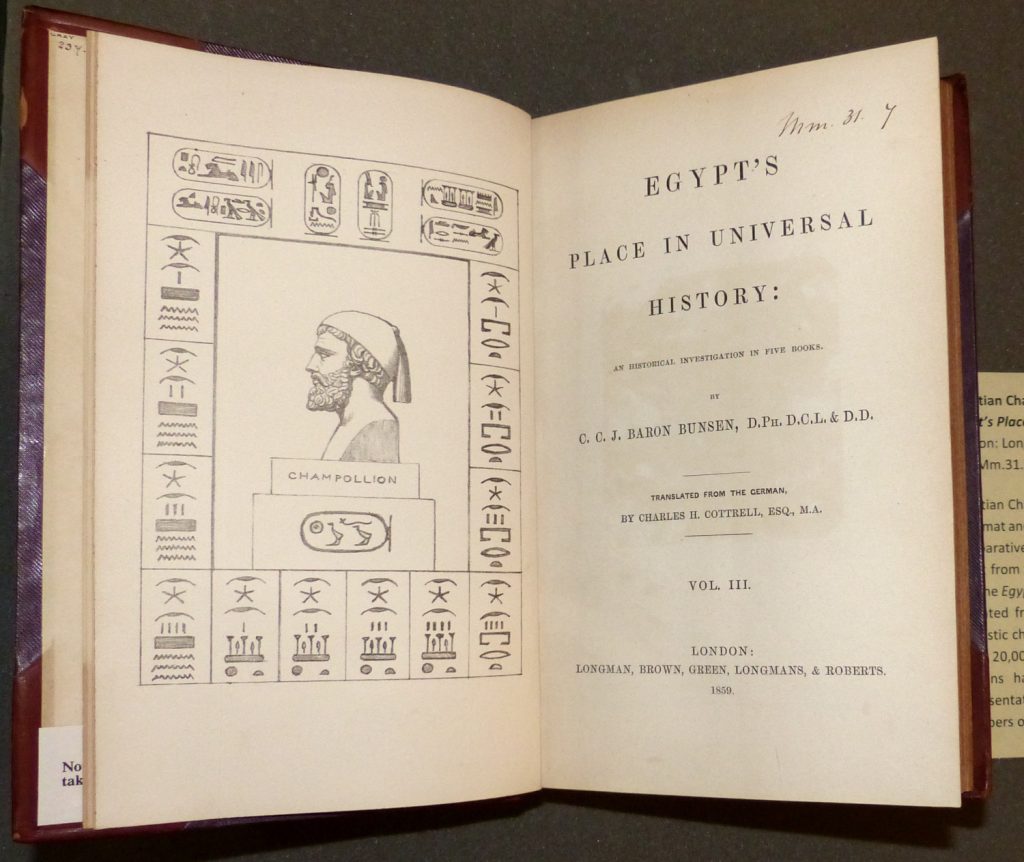

Christian Charles Josias von Bunsen (trans. Charles H. Cottrell), Egypt’s Place in Universal History, volume 3 (London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1859). (CUL Mm.31.7)

Another interesting book on display was written by Christian Charles Josias von Bunsen (1790-1860), a Prussian diplomat and scholar in Britain, a proponent of German biblical criticism and comparative philology, and one of the most influential writers on ancient Egypt from the 1840s through 1860s. His five-volume Egypt’s Place in Universal History argued that ancient people migrated from East to West and brought languages with them. Tracing linguistic diffusion, Bunsen’s third volume concluded humans were 20,000 years old and agreed with Leonard Horner that humans had been in Egypt for about 14,000 years. His book was representative of monogenism, the belief that all humans were one species, sharing common ancestors in Adam and Eve.

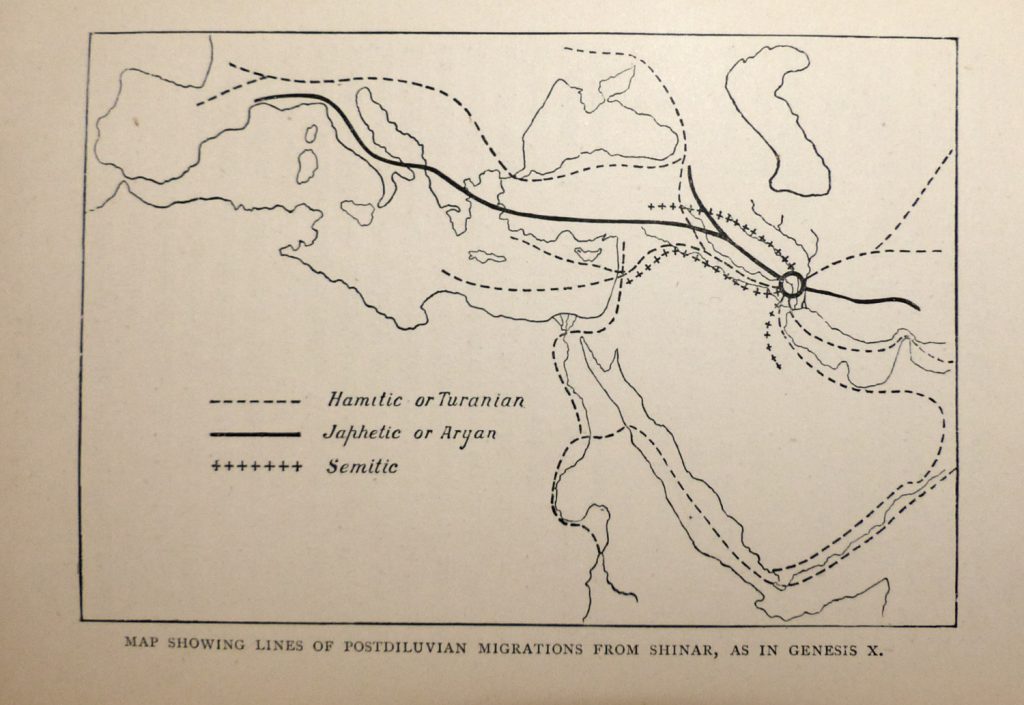

John William Dawson, The Meeting-Place of Geology and History (London: The Religious Tract Society, 1894). (Whipple Store 121:24)

John William Dawson (1820-1899) was a Canadian geologist and creationist who believed geology and Genesis were complementary. Dawson wrote many works on early Egyptian history including his penultimate The Meeting-Place of Geology and History. He attempted to show that “antedeluvian” people once migrated from ancient Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) as far as Europe before the biblical flood wiped them out. Afterwards some of Noah’s grandchildren (specifically the “Hamitic tribe”) migrated to Egypt, giving rise to Pharaonic civilisation. Dawson consequently argued that Egypt had no prehistoric period. His argument negated the gradual linear process of cultural evolution from “savage” to “civilised’ and instead suggested that all humans had been civilised since the moment of creation. His map shows “postdiluvian” migrations throughout the ancient Near East.

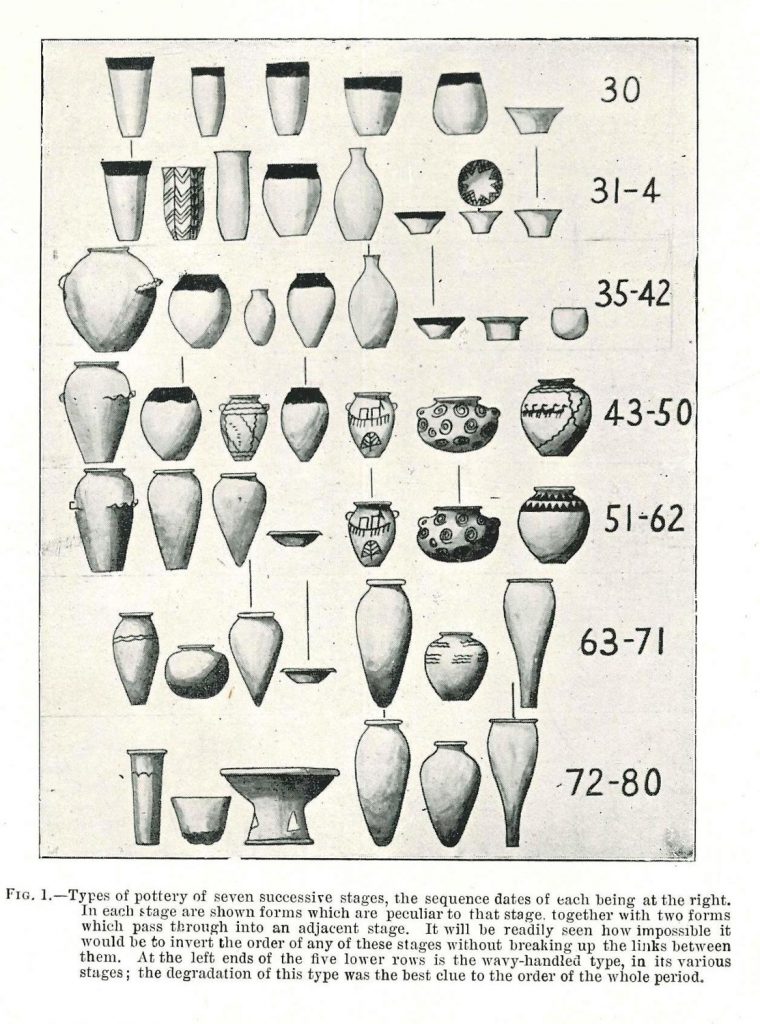

William Mathew Flinders Petrie, “Sequences in Prehistoric Remains,” Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland vol. 29 (1899), pp. 295-301 (CUL P460.b.56.30)

A major turning point in the study of Egyptian prehistory was the establishment of the concept of “predynastic” Egypt. In 1895, Egyptologist William Mathew Flinders Petrie (1853-1942) directed excavations at the ancient cemetery of Naqada, Upper Egypt. The human burials were different from anything previously excavated. The bodies were in a flexed position and buried with unrecognizable pottery. Petrie proposed the burials were evidence of a “new race” that had invaded from Libya, although he was soon corrected by French Egyptologist Jacques de Morgan (1857-1924) who argued the Naqada pottery was “predynastic” and dated to a period before hieroglyphic writing. Petrie had his field students draw the predynastic pots and then arranged the drawings in chronological order by tracing gradual changes in their form. The logical development of ceramic forms was informed by typological schemes developed in late-Victorian evolutionary anthropology. Petrie termed this relative dating technique “sequence dating.” It marked the first time Egyptologists used pottery alone to date prehistoric sites.

Many thanks to the Whipple Library and Cambridge University Library staff who assisted with the creation of this exhibition.