The original red-eye: Alcock and Brown across the Atlantic

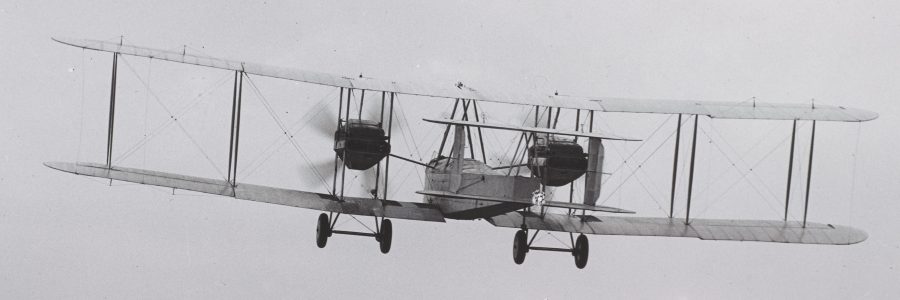

Almost a hundred years ago, over the night of 14–15 June 1919, Captain John Alcock and Lieutenant Arthur Whitten Brown became the first people to fly non-stop across the Atlantic Ocean. Competing for a prize of £10,000 offered by the Daily Mail, they flew from St John’s, Newfoundland, to Clifden in Ireland, a distance of 1,890 miles, in a twin-engined Vickers Vimy biplane. During the flight, which lasted more than sixteen hours at an average speed of almost 120 m.p.h., the pair overcame equipment failure, fog and ice, eventually crash-landing unhurt in a bog they had mistaken for a field.

Alcock and Brown were feted as heroes and knighted by King George V. To mark the anniversary of their feat, a new exhibition goes on display today in the Library’s Entrance Hall, drawing on the archive of Vickers Ltd and associated companies donated to the University Library in 1985.

John Alcock, a decorated First World War pilot, had formed a determination to attempt a transatlantic flight while being held as a prisoner in Turkey in the final year of the War. On his release he approached Vickers, whose Vimy bomber was a suitable machine for the ocean crossing. He was already established at the Vickers works in Weybridge, Surrey, when his agreement with the firm was confirmed by an exchange of letters on show. The attempt at the Atlantic crossing is not specifically mentioned in the correspondence, but it is perhaps a telling detail that as part of the deal, Vickers insured Alcock’s life for £500.

An electrical engineer by training, and an Observer in the Royal Flying Corps during the War, Arthur Whitten Brown gained his place on the transatlantic flight after a chance meeting with Alcock at Weybridge. His engagement as navigator was also settled by an exchange of correspondence; a letter of 9 April 1919 shows Brown’s attention to the details of the contract, covering matters regarding the sea passage to America, the purchase of kit, and the payments to be made in the case of various eventualities.

The Vimy used in the flight was transported to Canada by sea on the Furness Line’s steam ship Glendevon, and the bill of lading (an official receipt given for goods consigned for shipment), dated London, 12 May 1919, is on display. ‘One Aeroplane & 1 Hangar (loose and in packages)’, together with drums of fuel—noted as being ‘Inflammable’—were contracted to be delivered to Alcock in St John’s, Newfoundland, and were duly landed there on 29 May. Alcock and Brown had sailed earlier aboard the liner Mauretania.

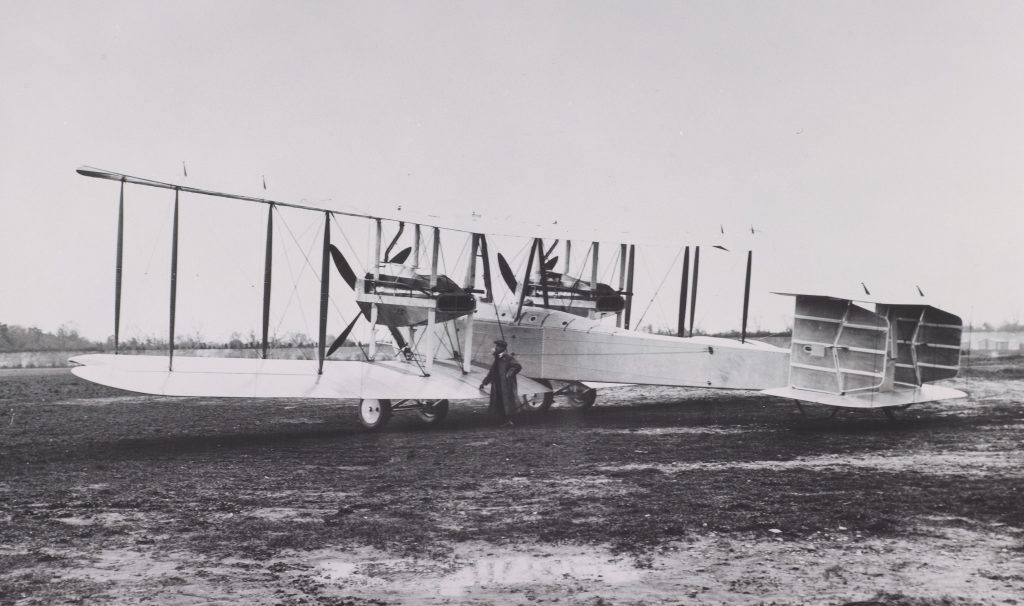

The aircraft was reassembled on a field near Quidi Vidi, on the outskirts of St John’s. A trial flight was made on 9 June, and Alcock dispatched a telegram from St John’s to the Vickers head office in Knightsbridge the following day. Although the trial was largely successful, there was a problem with the wireless transmitter which proved not to be satisfactorily resolved: it failed again shortly into the transatlantic flight.

Photographs in the exhibition, printed from negatives in the Vickers Archive, show the Vimy on the ground in Newfoundland, and taking off from ‘Lester’s Field’ (named after its owner, a haulage contractor who had levelled his grazing meadow for the purpose) at 1.45 p.m. local time on 14 June 1919 at the start of the transatlantic flight.

Alcock and Brown were accompanied in Newfoundland by a team of Vickers mechanics, carpenters and riggers. Having received the Daily Mail cheque for £10,000 on 20 June, they acknowledged the contribution of the entire Weybridge operation to their success by making a gift of £1,600 to the works. As recorded in the minutes of a meeting of the Vickers Air Committee on 17 July 1919, the firm supplemented the sum in order to allow a full week’s wages to be paid as a bonus to each worker.

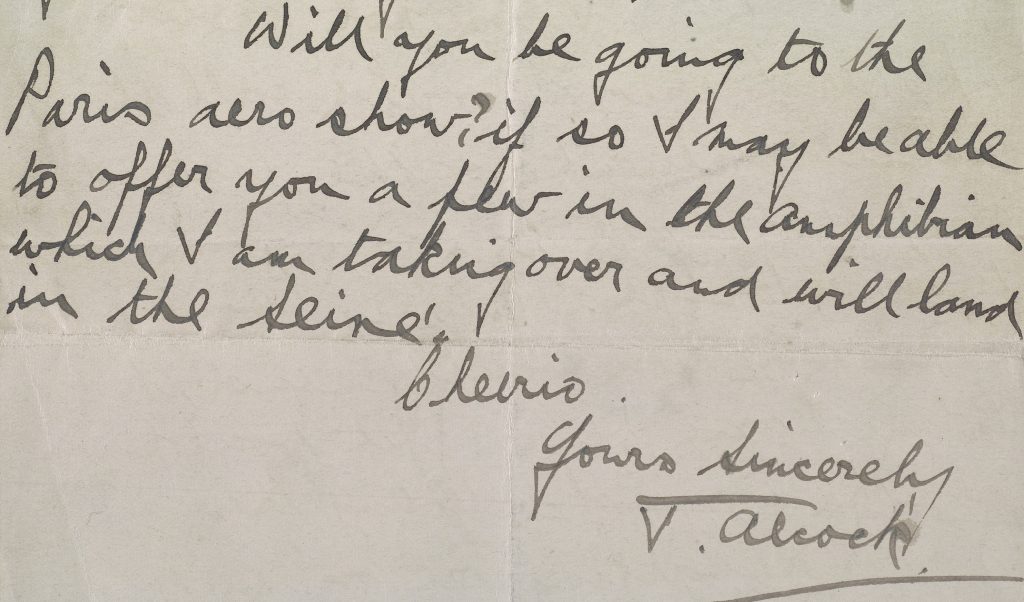

Sir John Alcock did not live long to enjoy his fame. Employed by Vickers as a staff pilot to test and deliver aircraft, on 18 December 1919 he set off to ferry a Viking amphibian to a display in Paris: he had intended to land it on the Seine. Instead he crashed in fog in northern France, and died from a head injury a few hours later. In one of the last letters he wrote, the final exhibit in the display, he invited an engineer, Mr Chorlton, to accompany him on the flight. Pressure of work forced Chorlton decline.

‘The original red-eye: Alcock and Brown across the Atlantic’ runs from Tuesday 28 May to Saturday 22 June, and can be visited during normal Library opening hours. The Vickers archive is a treasure-house for aviation history, and can be consulted in the Manuscripts Reading Room by anyone holding a valid reader’s card.

Images reproduced by permission from the Vickers Archives held at the Cambridge University Library.

Thrilled to read this full account as my late Grandfather worked on the plane that won the first non stop Atlantic flight by fitting heating & lighting apparatus. I have the original letter dated 7 July 1919 from Vickers Limited Works Manager to him acknowledging his contribution.

You may be interested in this.

105 years ago today! You might be interested in a letter, complete with envelope and stamp, I have that was carried on this flight. My great uncle who was a radio officer on ship, sent it to his father who lived near Bradford on Avon, advising him to keep the envelope and stamp!