Imagining Islands: Images of Island Exploration in Early Modern Travel Narratives

A guest post by Lauren Killingsworth, whose exhibition “Imagining Islands” can be viewed in the Library Entrance Hall from Monday 24th June to Saturday 27th July.

In 1910, Trinity College fellow and antiquarian John Willis Clark (b. 1833) bequeathed his library of rare travel books to the University of Cambridge. Today the collection is housed in the Department of Geography, which celebrates the centennial of the Geography Tripos this year.

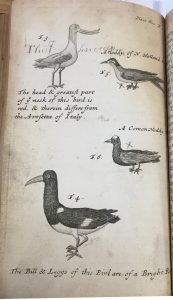

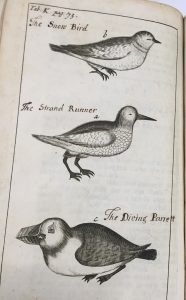

Sea-birds, from Friedrich Martens’ A voyage into Spitzbergen and Greenland (1694). An early owner has added captions in MS.

Clark’s collection contains hundreds of books illustrating the flora, fauna, and topography of distant lands. Travel narratives were a popular genre in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, captivating readers with tales of seafaring explorations, encounters with new cultures, and observations of new species.

Explorers often described the islands they called at en-route to their destinations. This exhibit highlights images of islands in travel narratives from the Clark collection. Maps, landscape views, and illustrations of animals took readers on journeys to the Canary Islands, the Greek Islands, São Tomé and Príncipe, Svalbard, and beyond.

In 1671, physician and naturalist Friedrich Martens (1635-1639) sailed to Spitsbergen (Svalbard) to conduct the first scientific observations of the island. He encountered the “Snow-bird” (b), the “Strand Runner” (a), and the “Diving Parrett” (c). The snow-birds were “so tame, that you could take them up with your hands.”

In the English translation of his narrative of the voyage, published in An Account of Several Late Voyages & Discoveries to the South and North (London, 1694) he recounts: “we fed them with Oatmeal, but when their Bellies were full, they would not suffer themselves to be taken up.” Martens was fascinated by the “very beautiful” diving-parretts (puffins) with “curious feathers,” explaining, “The sun shined at that time upon him, which made him look like gold, so as it dazzled our eyes almost.” Martens also encountered marine animals, including the “sea-horse” (walrus) which “stink naturally abominably.”

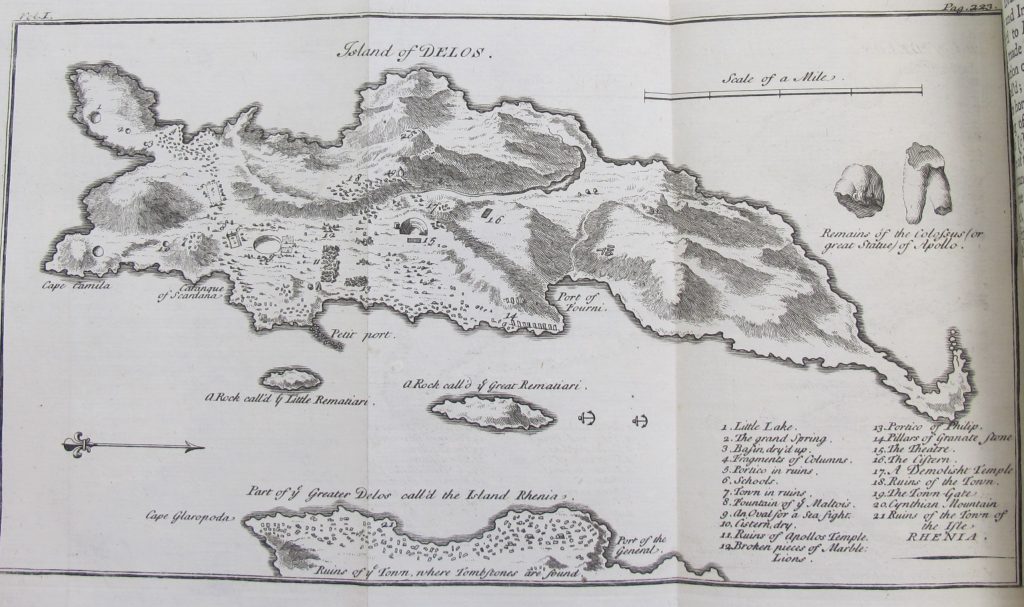

Map of the Island of Delos, from Joseph Pitton de Tournefort’s A Voyage into the Levant Performed by Command of the late French King (London, 1741)

In 1700, French botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656-1708) set out on a royally-commissioned “Voyage into the Levant” to investigate the natural history, geography, and culture of the Eastern Mediterranean. Tournefort visited the Greek islands, Istanbul, Armenia, and Georgia, describing the plants and antiquities found at each stopping point.

Tournefort’s “Map of the Island of Delos”, shown here in the version from the English edition of his voyage in 1741, illustrated the ancient ruins discovered on the island, noted in the key. These included a water basin (#9) (now empty and “fit for nothing but Sailors and Fishermen to dance in”)— surmised to have once held “very small” ships for ancient sea fight spectacles. The map also illustrated the remains of an Apollo statue. Tournefort conjectured that the colossal statue had been made from “one single block of marble…designed for the Frontispiece of a Temple.”

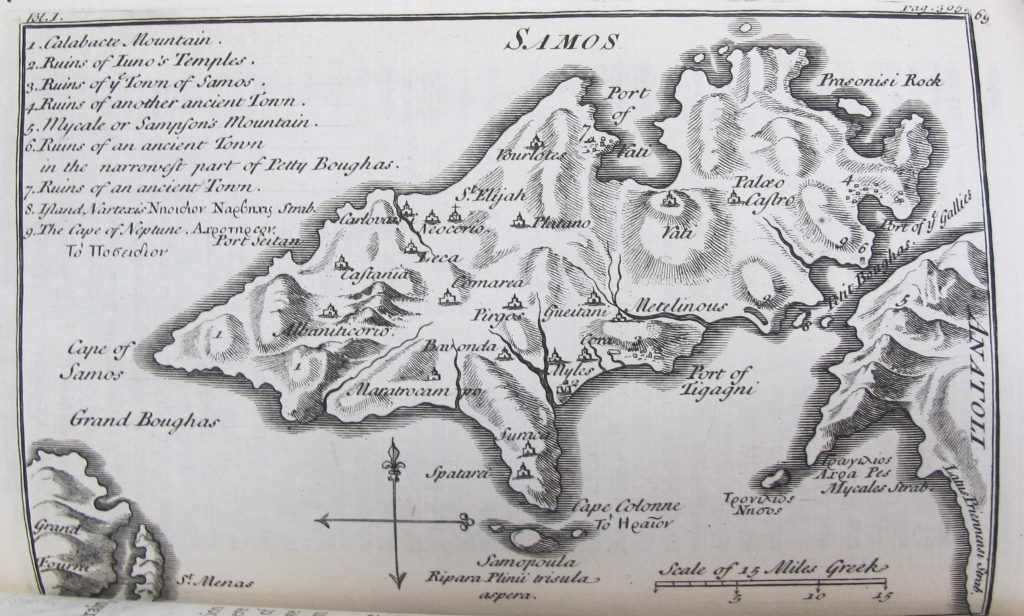

Tournefort reached the Greek island of Samos in 1702, careful to avoid the bandits that lurked in the straights surrounding the island. Tournefort described Samos as a mountainous island, “very populous and well-manured,” with the “best and beautifullest” grapes, and “very fine” silk. The map located sites of ancient ruins, including the “Temple of Juno” (#2) (once a “great Temple fill’d with Pictures and antique Ornaments”) and the “ruins of another ancient town” (#4), described as a “world of broken pillars.”

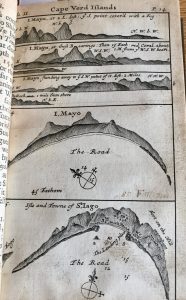

William Dampier (1651-1715) voyaged to New Holland (Australia) in 1699, stopping at the Canary Islands, Cape Verde Islands, and Brazil before rounding the Cape of Good Hope.

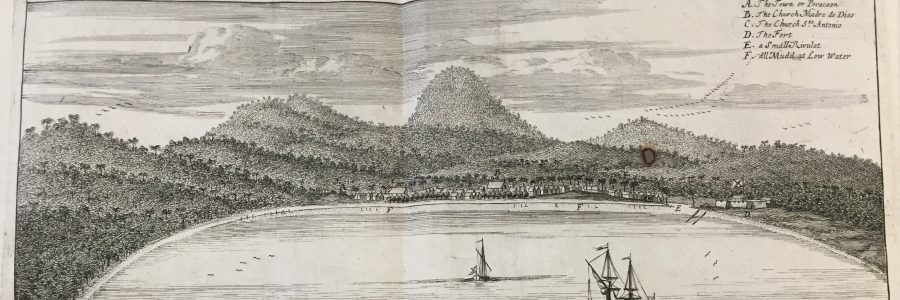

In the chronicle of his voyage, Dampier included several views of the Island of Mayo as it came into view from the ship. The Island of Mayo and the Island of St. Jago were one of several islands that comprised the Cape Verde Islands, a stopping point for salt and sugar that was feared for being “miserably infested” with pirates. Dampier noted that figs and water-melons were the chief fruits, flamingos and guinea-hens the main fowl, and goats and cows the chief land-animals (though pirates had “much lessened the number of those”).

Upon arriving in an inlet in New Holland (later named “Sharks Bay”), Dampier observed a “few land-fowls.” This copy has been annotated by one of its previous owners, who noted “This I have seen” next to the bird illustrated in “Fig 3,” and made “X” marks next to the birds he had (presumably) missed. Travel narratives could serve a practical purpose as travel guides, in addition to their function as popular entertainment and armchair travel.

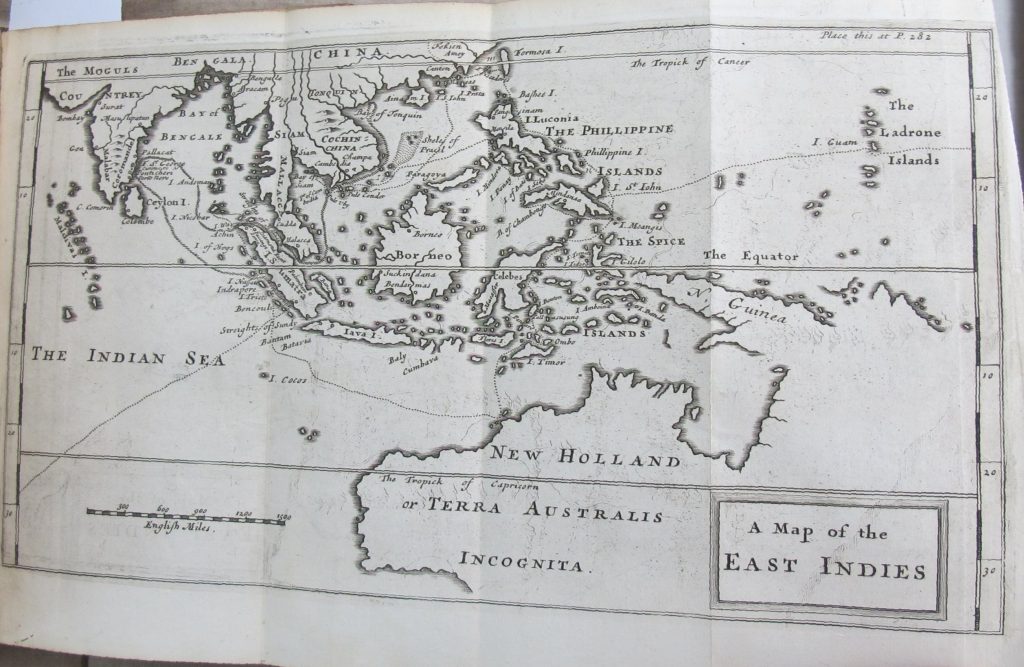

Dampier had earlier chronicled his circumnavigation of the world from 1679 to 1691, illustrating his journey through a series of maps in his popular “New Voyage Round the World.” “A Map of the East Indies”, from a 1703 edition, shows his journey through East Indies and his stopping points at the Ladrone Islands, the Philippines, Formosa (Taiwan), Poulo Condor, the coast of China, and Sumatra.

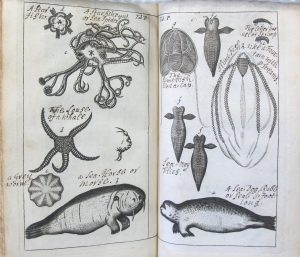

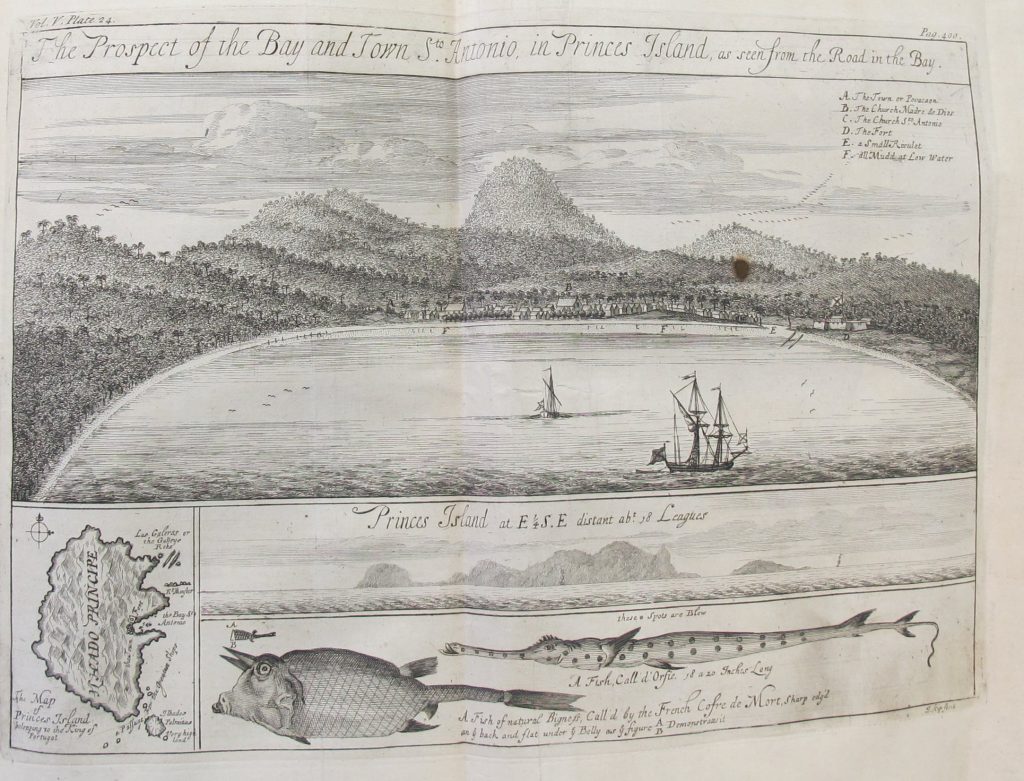

The plate below, from Jean Barbot’s “A Description of the Coasts of North and South-Guinea” (A Collection of Voyages and Travels, vol. 5, 1746), portrays the different forms of visualizations employed in travel narratives: bird’s eye views, sea-level perspectives, maps, and natural history images. “Princes Island” (today São Tomé and Principe) was under control of Portugal. Barbot (1655-1712) described the 400 houses and two parishes of the main town, which was surrounded by “very mountainous” and “woody” fertile country. He also described two fish he saw in the island’s bay. The “French Coffre de Mort” was “as sharp as the edge of the knife.” The other was “eel-like…looking at a distance like a flute” and “very good to eat.” Barbot was an agent of the French Royal African Company and made slaving voyages to the West Coast of Africa in the late 1600s. His travel narrative dehumanized the indigenous populations of West Africa and is demonstrative of the atrocities of the slave trade.

Prince’s Island, from Jean Barbot’s A Description of the Coasts of North and South Guinea (London, 1746)