Piecing Together the Evidence: Cataloguing a Greek Manuscript

Alongside conservation and digitisation, the Polonsky Foundation Greek Manuscripts Project encompasses the creation of detailed catalogue descriptions for each manuscript, to accompany the images published online. While some of the Greek manuscripts in Cambridge have been intensively studied in the past, much of the benefit of a cataloguing project lies in examining, analysing and describing those on which very little information has been published in the past. The scope for fresh discoveries can also make these some of the most stimulating manuscripts for the cataloguer to investigate. They are often those whose content is neither rare enough nor early enough nor unusual enough in its textual variations to have attracted attention for editorial purposes. This does not negate their potential value as witnesses to a particular history of production, use and reuse.

Such information as has hitherto been available in these less-studied cases tends to focus on the identification of contents, but much of what can be learned about and learned from a manuscript lies in the clues that can be assembled from the physical details of its materials, script, ornament, construction and organisation, and how these relate to the text. In the course of cataloguing we record these details and by combining them try to understand the purposes and processes of creation and modification which have produced the object that now exists.

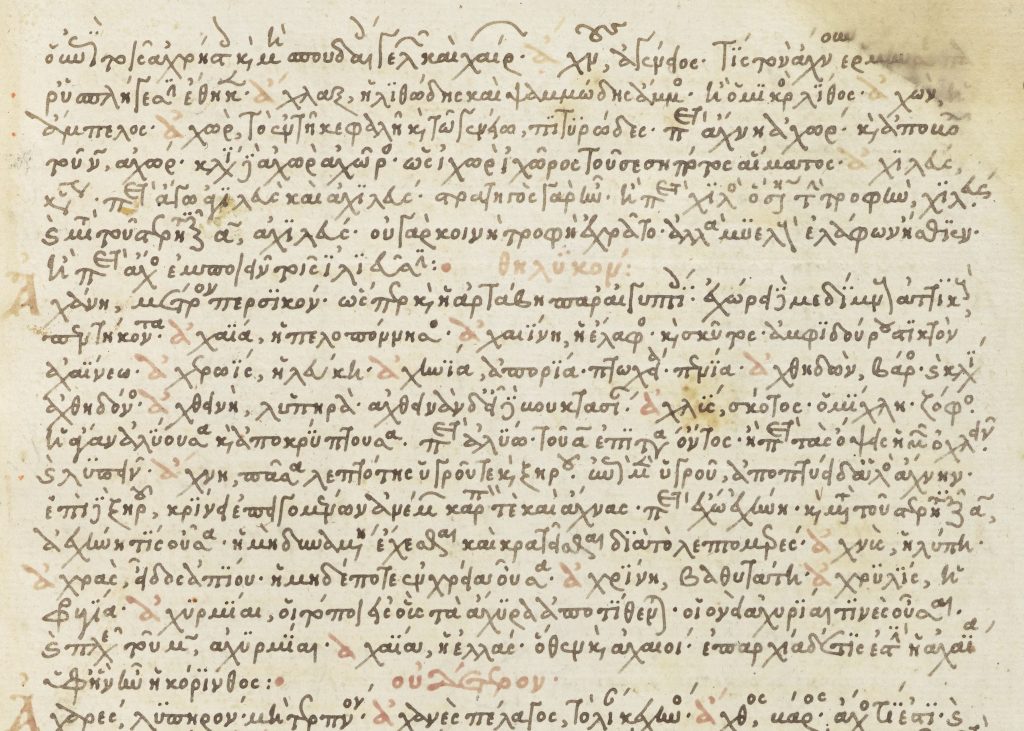

An example of the ways in which the life of a little-studied manuscript can be illuminated by the assemblage of different types of physical evidence is MS Kk.5.25, a late 15th-century manuscript containing a lexicon or glossary whose actual authorship is unknown, but which was traditionally attributed to the 12th-century Byzantine historian Ioannes Zonaras. At the end of this manuscript, the lexicon itself is followed by a number of entries for words which had been omitted from the text during its original copying, presumably inadvertently, and then by a number of brief additional lexicographical lists. These include glosses of unusual vocabulary from the Pauline Epistles, Hesiod and the Odyssey, Egyptian names for the months, and words for the noises made by different animals.

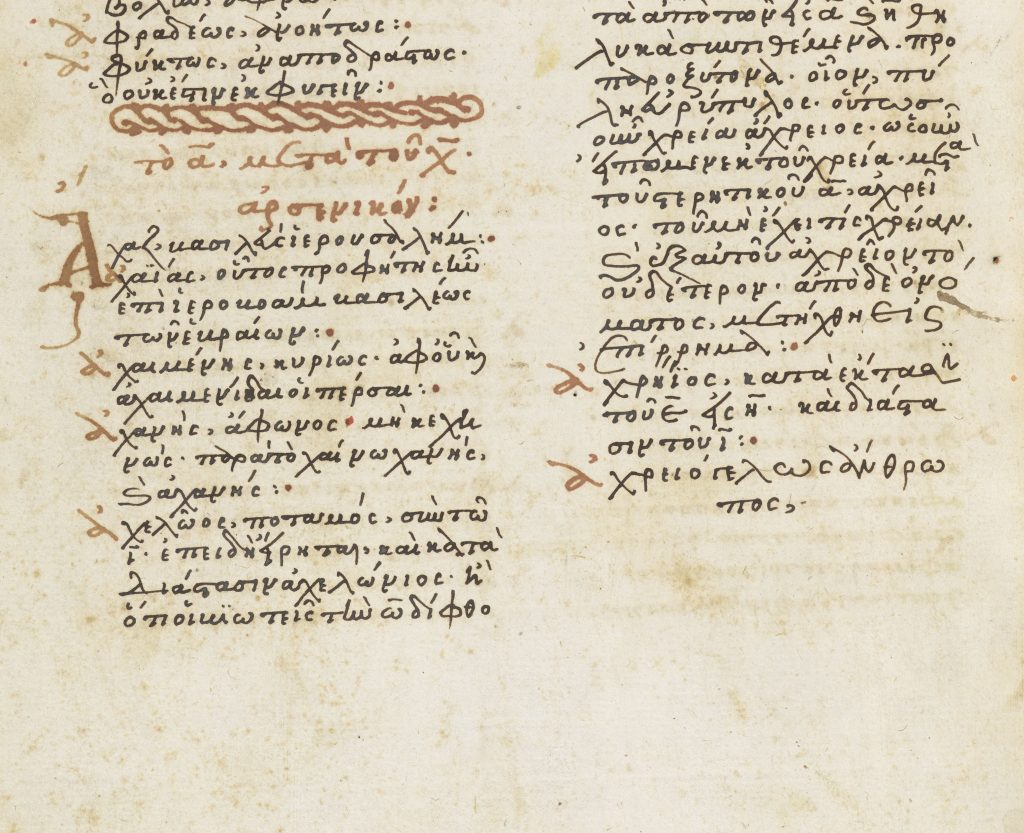

The most immediately conspicuous peculiarity of the manuscript is the ornamental headpiece at its beginning, show at the top of this post. While the overall form is consistent with the Byzantine tradition, the style is more suggestive of the western European Renaissance. The script, however, is in a calligraphic style typical of Byzantium in its last centuries. This combination suggests perhaps the work of Greek-speaking scribes who had relocated to the West, most probably Italy, or production in an eastern Mediterranean territory under western influence, such as Venetian-ruled Crete. Lexicographical works such as this were of use to native Greek-speakers, but perhaps especially appealing to western humanists wishing to decipher the more obscure vocabulary of Greek texts.

While the style of script is similar throughout, the first 56 folios are discernibly the work of a different hand from the rest. This change of hands is accompanied by a simultaneous change of paper, indicated by the watermarks. A further change of material occurs at the end of the manuscript, where the very last quire (the booklets of eight folios from which the volume is assembled) consists of a third type of paper, although here the hand is the same one responsible for the bulk of the text. What does occur at almost the same point as this second change of material is a change of content. The main text of the lexicon ends on the last folio of the penultimate quire, while the remaining space on this folio and the whole of the last quire, composed of the third paper, are filled with the addenda to the lexicon and the supplementary texts. Thus it seems clear that these were an afterthought, added at the patron’s request by the original scribe, but ordered after the original commission had been completed, by which point the scribe had moved on to using a different paper stock.

Reconstructing what happened in the early part of the manuscript requires the consideration of further types of evidence. It is clear that the division of labour between two scribes was not originally planned. The change of hands occurs not at a logical transition point for a prearranged allocation of work but in mid-sentence. Nor was this a matter of the copyist whose work appears first in the manuscript (Hand A) stopping work at the end of a quire and the other scribe (Hand B) picking up from that point. The text of the last page copied by Hand A (f. 56v) is larger than usual, indicating that it was being stretched to fill the remaining space, so as to join up with the beginning of Hand B’s text without leaving a blank space. This shows that the chronological order of events at this transition was the opposite of the order in which folios follow each another in the manuscript: the work done by Hand B already existed before Hand A reached this point.

Confirmation of this comes from the quire signatures, the numbers marked on each quire to indicate the order in which they should be bound together. Hand A’s work filled seven quires, but the beginning of the first quire containing Hand B’s text (f. 57r) bears the number 6, and subsequent signatures follow the same sequence. From this it becomes clear that Hand A’s work was a replacement for previously existing text which had filled only five quires. These could have been lost due to damage, though comparison of the watermarks with dated examples indicates that both scribes worked in the last few decades of the 15thcentury or perhaps the first years of the 16th, leaving a relatively short interval in which such damage could have been done.

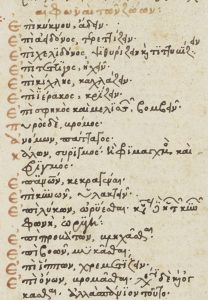

A more likely explanation comes from the layout of the text. Hand A’s work was written in two columns, with each entry beginning on a new line, and the same is true of nearly all of Hand B’s. However, the first three pages copied by Hand B are written in a single column and with each sub-section (for masculine, feminine and neuter nouns, verbs and adverbs beginning with a particular pair of letters) forming a continuous block of text. The beginning of each entry is marked out only by the use of red ink for the first letter.

CUL MS Kk.5.25, f. 57r: The original layout of the early part of the manuscript (by Hand B), with lexicon entries following each other in continuous text

Such a layout was common in manuscripts of this text, but was not an ideal arrangement for finding entries in a reference book, especially given that the entries are sorted into alphabetical order only by the first two letters of the word. This disadvantage presumably explains why Hand B switched to a more easily navigated layout for the remainder of the text, whether on the scribe’s own initiative or the patron’s. Assuming that the whole of the text up to this point had been written in continuous fashion, here is a plausible explanation for the later decision of either the original patron or some subsequent owner to remove the early quires, whose text was arranged in this way, and replace them with text more helpfully organised, employing a different scribe to do the work. This would also explain why only five quires were originally needed for content that fills seven with the present layout. As for the survival of three pages in the original layout, we may speculate that the owner did not think it worth the expense of replacing this whole quire or dismantling it and reassembling it with new outer leaves, merely for the sake of three pages out of sixteen.

By recording and assessing the specifics of an individual manuscript such as this, the process of cataloguing can root its abstract content in a material, human reality of purposes, practicalities and interactions, though much of what can be reconstructed remains a matter of inference and plausible conjecture. It also inevitably raises further questions which remain unanswered. In this case, for instance, having established that the opening quires of were replacements for earlier originals, it becomes clear that the evidence of western European production provided by the ornamental headpiece can only be certainly applied only to these. This reopens the question of where the original portion of the manuscript was produced, and hence of the cultural context of the original commission, the intervention that changed the layout of the text, and the commissioning of the supplementary texts added by the original scribe. Where we cannot answer questions, cataloguing can at least draw attention to them and, in conjunction with digitisation, provide evidence that could be used for their resolution.